Netflix Says Algorithm Is Protected by First Amendment in 13 Reasons Why Suicide Lawsuit

Is a required content warning or algorithm change a violation of the First Amendment?

Netflix is being sued by the grieving father of a teenager who allege that the Netflix show 13 Reasons Why inspired their daughter's suicide. Netflix counters that the suit infringes on its freedom of speech, arguing that its algorithmic content recommendation is protected by the First Amendment.

The streaming service has filed a motion to strike down the lawsuit by invoking California's anti-SLAPP statute, which permits the dismissal of complaints that infringe upon protected speech. The lawsuit, Herndon v. Netflix, was filed in California's Santa Clara County Superior Court earlier this year.

The plaintiffs in the case are John Herndon, his sons, and the estate of Herndon's daughter, Isabella, whose suicide was allegedly precipitated by watching 13 Reasons Why. They allege that vulnerable viewers were not adequately shielded from or warned about the show's highly graphic and suggestive content. The lawsuit points to "Netflix's failure to adequately warn of its Show's, i.e. its product's, dangerous features."

Netflix argues that such accusations endanger expressive rights. "Creators obliged to shield certain viewers from expressive works depicting suicide would inevitably censor themselves to avoid the threat of liability [which] would dampen the vigor and limit the variety of public debate," Netflix states in its legal filing.

Ari Cohn, free speech counsel at TechFreedom, says that legal precedent seems to be on Netflix's side. "For ages, plaintiffs have attempted to sue over harms allegedly caused by movies, books, newspaper or magazine articles, television shows, video games, and other media—but they nearly always fail," he explains. "In case after case, courts have held that the ideas, words, and depictions within a product are not subject to products liability law."

Netflix also argues that content-based restrictions would expose an enormous amount of creative works to the risk of censorship, pointing to the trope of teen suicide that stretches from Romeo and Juliet to Dead Poets Society to 13 Reasons Why.

"The point that Netflix is making is a good one, and it isn't limited to suicides," says Eric Goldman, a law professor at Santa Clara University and co-director of the High Tech Law Institute. "In fact, one could imagine any number of different vulnerabilities that members of an audience have," he says. "Keep going down the list, and you could imagine having thousands of warnings. This has no natural limit to it."

The lawsuit against Netflix also argues that the algorithm the company uses to recommend shows and movies is at fault for encouraging suicide by foisting 13 Reasons Why upon suggestive teens.

The company should be held liable, the lawsuit maintains, because of "Netflix's use of its trove of individualized data about its users to specifically target vulnerable children and manipulate them into watching content that was deeply harmful for them—despite dire warning about the likely and foreseeable consequences to such children."

Netflix argues that its algorithm is no different from any other editorial choice and is therefore protected by the First Amendment. Highlighting specific shows for Netflix users is no different than "the guidebook writer's judgement about which attractions to mention and how to display them, and Matt Drudge's judgments about which stories to link and how prominently to feature them," the company argues.

Netflix's "recommendations fall within the well-recognized right to exercise 'editorial control and judgement,'" the company states. "The fact that the recommendations 'may be produced algorithmically' makes no difference to the analysis. After all, the algorithms themselves were written by human beings."

Free speech lawyer Cohn agrees. "While the Supreme Court has not squarely decided the matter, trial and appellate courts have held that computer code is 'speech' for First Amendment purposes, because the code is simply another language chosen to express ideas," he says. "In Netflix's case, their algorithm is plainly expressive: They serve to communicate to viewers that they might enjoy certain content based on their activity and preferences. Such expression is protected if automated just as it would be if done manually."

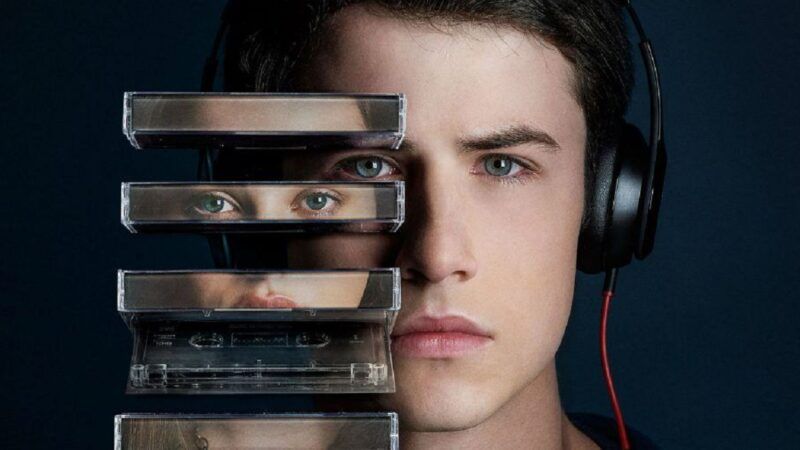

13 Reasons Why has been a big hit for Netflix since it premiered in 2017. The four seasons of the series depict the lead-up and fall-out of a high school student's suicide through a box of cassette tapes that chronicle her reasons for taking her life.

Cited in the Herndon family's lawsuit against Netflix is a 2019 study from the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry titled "Association Between the Release of Netflix's 13 Reasons Why and Suicide Rates in the United States." The study claims to have identified an unprecedented 28.9 percent jump in suicides among American teens in the month following the show's premiere. After the study made headlines, Reason Senior Editor Robby Soave questioned its findings. "The study is bunk," Soave reported. "It does not even begin to demonstrate that 13 Reasons Why is the cause of the phenomenon the researchers are documenting….Researchers have no proof that the teenagers who committed suicide over the observed time period had watched the show, or that they heard about the show, or that their deaths had anything to do with the show—this is all purely theoretical."

Court hearings in Herndon v. Netflix are scheduled for November 16. Interested parties on both sides of the debate over technology and free speech will be watching closely.

"We live in an era of fear of technology," notes law professor Goldman. "This [lawsuit] is just another manifestation of this very long arc of the 'computers as killers' narrative."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

The company should be held liable, the lawsuit maintains, because of "Netflix's use of its trove of individualized data about its users to specifically target vulnerable children and manipulate them into watching content that was deeply harmful for them

Because killing your customers is a successful business model?

(Don't give me the booze and cigarettes argument. They kill you slowly).

Pfizer and Moderna don't seem to have a problem with it.

They have hundreds of millions of mandatory customers.

I am making a good salary online from home .I’ve made 97,999 dollar’s so for the last 5 months working online and I’m a full time student .DEc I’m using an online business opportunity. I’m just so happy that I found out about it.

For more detail … Visit Here

Be forewarned, People!!

Do not Visit There!!!

I have learned what lurks there.

At Lousy Book Covers, a recent title was "22,000 videos sold: my fetish self-exploration turned into Real Money on Clips4Sale. Now it’s your turn!: Earn money from home: My clips4sale step-by-step setup guide to your adult home business".

Don't debauch your dignity for dineros!

Heed my warning!

Then let us sue politicians who slam their fists on the table every time there is a church burning, or something similar, and suddenly church burnings skyrocket.

What? Politicians won't allow that?

Odd.

Hey Guys, I know you read many news comments and posts to earn money online jobs. Some people don’t know how to earn money and are saying to fake it. You trust me. I just started this 4 weeks ago. I’ve got my FIRST check total of $3850, pretty cool. I hope you tried it.THs You don’t need to invest anything. Just click and open the page to click the first statement and check jobs .. ..

Go Here..............Earn App

If someone kills themself after watching a movie, they had SERIOUS mental issues PRIOR. The father should be seeking therapy to properly grieve instead of pointing his finger. It's amazing how many people do not realize that all their problems and all their solutions are in THEMSELVES. Instead of bullsh*t CRT, they should be teaching mental health in schools!!! No, no. That would actually be BENEFICIAL... can't do that.

I suspect that after Goethe's "Sorrows of Young Werther" was published in 1774, most people who committed suicide had not even heard of the book or even if they had, were going to commit suicide anyway, book or no book. No way of proving my suspicion and even less provable is whether the book deterred suicide among its readers. What is true is that after the book became a topic of discussion, some people paid more attention to suicide and then connected their awareness of the book to their new found attention on suicide.

OT -- I can't load comments on the MLK gun permit story. I've tried two browsers (Firefox and Chromium), including disabling all ad-blockers, and bupkis. The "Show/Hide comments" link does bupkis. Yet the comment count continues increasing slowly. Other stories, like this, seem to work (supposing this comment gets posted).

Anybody else having similar problems? Last time anything similar happened was over last year, maybe the year before.

Yes, been having intermittent problems with it.

the roundup thread is doing it too

The roundup thread is doing something really weird for me. I got to the comments the first time I tried, and was able to, and continue to be able to post comments from there. But when the page reloads after submitting the comment, I can't get into the comments in the manner described by ABC. But the comments are being posted, if I go back to that first loaded page and reload it. Perhaps the squirrels are doing something epically strange with the URLs containing a comment anchor?

And the same thing is happening here. Going up and deleting the comment anchor got it to reload in such a way that the comments loaded when I pushed the button.

I blame Preet.

When I post a comment, I have to go back to the home page and then find the article and load the comments section all over again.

I guess that's one way to generate click throughs...

I have been having issies

We know.

Are "issies" like issues, only for toddlers? ;]

Yes. It's funky today. You can close the page and reopen it. Then it will work. Once. But it'll repeat.

As some others suggested, reload works, but at least in my case, I have to shift-reload (to bypass the cache) the article itself, not with #comment-12345 appended or even #comments appended. Then click "Show comments" and see all comments, including mine.

Maybe they're working oh-so-slowly on adding an edit button, and this is the price to pay. I once worked on a system which had one server, period (25 years ago). It was production, test, dev, everything. Changing one file was easy to save the original. Changing several files at once was touch and go.

Facetiously, maybe your problem is having a screen name that reads like an ancient Cthulhuvian curse.

Seriously though, I have had comments seemingly not go through but then appeared after hitting the refresh arrow. The back arrow often goes to a cached previous version of the page for me.

Try right click on Show Comments button and "Open in new tab".

While I grieve for the father and other family members, watching a movie is not the cause. There has to be extenuating circumstances that led to the daughters suicide. She must have had issues beforehand. I am saddened, but netflix is not at fault.

That would take personal responsibility into account (Father, daughter, family, friends?). We can't have that.

If someone kills themself after watching a movie, they had SERIOUS mental issues PRIOR. The father should be seeking therapy to properly grieve instead of pointing his finger. It's amazing how many people do not realize that all their problems and all their solutions are in THEMSELVES. Instead of bullsh*t CRT, they should be teaching mental health in schools!!! No, no. That would actually be BENEFICIAL... can't do that.

But presumably Netflix has deep pockets on tap.

Traditionally, that was a parent's job.

And how is Netflix supposed to know if a given user is particularly vulnerable? I can kinda see Facebook managing something, since their users provide somewhat detailed input on occasion, but Netflix has nothing other than search terms and shows wishlisted and watched to go on.

"Netflix's use of its trove of individualized data about its users to specifically target vulnerable children and manipulate them into watching content that was deeply harmful for them—despite dire warning about the likely and foreseeable consequences to such children.”

Because the father’s lawyer says they’re purposely trying to make teenagers suicide, apparently.

Even for Facebook, it would be near impossible, because they presumably aren't pulling death certificates of their users and feeding that into their algorithm. Their "user retention" algorithm might notice that it is a bad idea to show certain content to a certain subset of the population, but it would have no idea why the user stopped logging in, it just knows/cares that they left the platform.

they presumably aren't pulling death certificates of their users and feeding that into their algorithm.

I wouldn't be so sure about that....

Exactly. Regretfully, the father seems more involved in pursuing legal action rather than parenting.

my mom said listening to Ozzy would turn me into a devil worshipper, but now every time K-State runs onto the field they do so to Crazy Train and she goes bananas

tv did not cause a suicide. neither did that creepy chick.

Were you even allowed to listen to Suicide Solution?

dude she burned (lit.on.fire.) my Blizzard and Diary cassettes. straight out of Detroit Rock City. Tipper Gore's fault.

What you choose to fill your head with and dwell on has an effect on how you approach the world. That’s not an argument for Netflix controlling it, but it is one that it is our responsibility to do so.

I haven’t seen it, but there’s even a trigger warning on Prince of Egypt. Does this show have any content warning on it? Not that that would stop an unsupervised teen from accessing whatever she wants.

Huh, I don't know how I missed this, but Bill Gates has been retroactively #MeToo'd at Microsoft. Apparently, he asked out some women while he worked there. It's as if people forget his now ex-wife (one of the richest women in the world) used to be an employee.

OMG! Some dude asked a woman out on a date! Get out!

He looked at her ankles!

Well, what did she expect, walking around with her ankles showing?

You forgot "Heathers". A comedy about teen suicide.

I love my dead gay son!

Let's not forget "Better Off Dead". Still one of my favorites.

go that way, real fast. if something gets in your way, turn.

a study ... in mopishness

It's a damn shame when folks be throwin' away a perfectly good white boy like that.

Also, for those who noticed it, Monique starts Lane's Camaro, and then hands him the still broken fuel pump.

Yeah, because THAT is the one ridiculous part of that movie.

Savage Steve Holland was a genius at over the top satire. My friends still can't discuss "two dollars" without saying it like an obsessive, threatening paperboy.

Wait, wait a minute...Oh. Oh! Ugh! Outrageous! I think I just froze the left half of my brain! Look! I can't move my right arm!

*Points gun loaded with blanks at Beetlejuice*

I will go insane, and I will take you all with me.

Only in that it's used to cover up a bunch of murders!

Just like to kill a mocking bird caused the death of John lennon

Give that man an award

I always take Catcher in the Rye to my shootings.

father should sue himself for not more closely monitoring his teenage daughter's viewing habits...how bout that?

everything always has to be someone else's fault.

Both parents should be sued for knowing having a child. Leads to the eventual death of a human being 100% of the time.

The shorter the Constitution, terser the corpus of laws, and lower the taxes on individuals, the more happiness and life worth living. Prohibitionist laws evidently make the sharpest difference. Over at Libertrans.us anyone can see how suicide rates increased sharply when beer was a felony in the U.S. Suicide rates tipped up after Reagan-Biden-Bush prohibition and asset-forfeiture laws became entrenched. Suicides rates drop where governments stop sending men with guns to coerce over storied sumptuary violations.

"Netflix's failure to adequately warn of its Show's, i.e. its product's, dangerous features."

Are the "dangerous features" comprised of speech? Yes? Dismissed with prejudice. Next case please.

How can an algorithm be speech? It is no more 'speech' than the trigger of a gun is 'speech' - or than a military attack drone is speech. An algorithm is nothing but direct orders - executed without error or further instructions.

Netflix may well not be responsible for this - but it must be on the basis that the algorithm is not responsible. Not that the algorithm is 'protected.

An algorithm is nothing but direct orders - executed without error

Until you throw a random element into it.

Except somebody is deciding what those orders are. It's speech just the same as what I am doing now is speech, even though all I am doing is issuing a series of commands to my computer to carry out tasks automatically.

never give up quotes

never give up quotes

While I grieve for the father and other family members, watching a movie is not the cause. There has to be extenuating circumstances that led to the daughters suicide. She must have had issues beforehand. I am saddened, but netflix is not at fault. lagu lir ilir berasal dari daerah

I recall when it was Dont Fear The Reaper blamed for teen suicides.

More cowbell!!

Although, Blue Öyster Cult was probably one of very few groups so accused who actually were sincerely Satanic.

The freedoms enumerated in the First Amendment are probably the furthest from being absolute rights.

You can't just call your ideology a "religion" and be free to worship it as you please. Look at how Scientology got categorized as a "religion" - through threats of lawsuits. And then there is that ideology masquerading as a religion, that is Islam.

Freedom of speech is constrained by defamation laws, and the freedom of the press is by libel laws, though destructively diminished by the courts. And let's not forget "yelling fire in a crowded theater", incitement, etc.

Even freedom of association needed to be extrapolated from freedom to assemble to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Question: How many know what order our first amendment was, in the submissions to the first Congress for entries in the BOR?

Hint: It wasn't the first.

You can't just call your ideology a "religion" and be free to worship it as you please.

Uh...yes, you can.

Infinite-loop-be-gone

There is a novel legal issue here. The mere availability of a particular movie absent a disclaimer isn't that issue.

But the allegation that the Netflix service conditioned a particular customer - that it watched what they watched and recommended them a steady diet of particular content, that's a bit different. I don't think it's presented here, since this reporting at least seems to emphasize that one movie, which almost certainly isn't going to be enough for them to make a case.

But I don't believe it's a settled legal question whether a service could be liable for systematic presentation of particular (classes of?) content, where that systematization is, let's say, in reckless disregard for the resulting content environment created and the potential effects on the viewer. We don't have to get all the way to Clockwork Orange before conditioning someone with content becomes harmful. And we don't have to get to harmful before trial lawyers will try to make a case out of it...

He looked at her ankles!

Pokearc

13 Reasons Why is one of my best series. I watch it on mycima