California Democrats Want To Make It Harder for Voters To Challenge Their Power

Political class rallies behind making the infrequently used recall mechanism more difficult to deploy

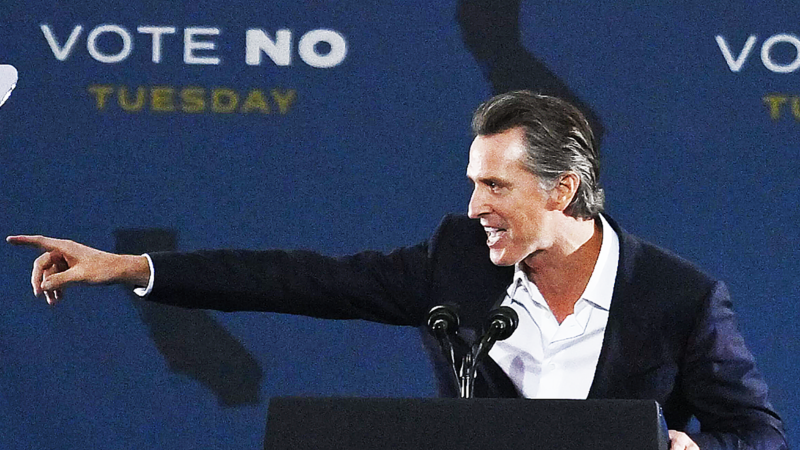

Today, California is holding its second-ever recall vote for a sitting governor. Unlike Gray Davis in 2003, Democrat Gavin Newsom is widely projected to survive the effort. The recall mechanism itself, however, may not prove so lucky. At least not in its current form.

Why? Because Democrats and their empathizers in the media and academe are talking themselves into the conclusion that one of progressivism's crowning electoral achievements, originally aimed at a democratically unaccountable machine, has become an anachronism now that Democrats are the ones pulling all the levers.

"For starters, California's recalls can happen in off-years, which makes them ripe for manipulation by the minority party," The New York Times editorialized Monday (please note the conspiratorial/pejorative word choice; it's standard issue in these efforts):

Voters in off-cycle elections generally skew older, whiter and more conservative, a recent study led by the University of California, San Diego, found. In other words, not very representative of California's population….The leading candidate is the Republican talk-radio host Larry Elder, whose conservative policy positions—including his opposition to mask mandates, abortion rights and a minimum wage, as well as his troubling views on women's rights and climate change—aren't in line with any statewide election result in California for decades.

Contra the Times, the purpose of the century-old recall feature, which has only made it to the ballot 11 times for state elected officials (six of whom were removed), was not to ensure that California's public representatives match up demographically and ideologically with the electorate, but rather to act as a between-elections check on corruption, incompetence, or whatever the relevant voters deemed a firing offense. The second California official to be successfully recalled, back in 1913, was Democratic state senator Edwin Grant, whose San Francisco constituents did not care for Grant's fervent opposition to the time-honored local industry of prostitution.

But "what was path-breaking and innovative a century ago," warned public policy professors Henry Brady and Karthick Ramakrishnan in Monday's Los Angeles Times, "looks anachronistic and downright dangerous today." ("Dangerous," alas, is a not-uncommon political-class adjective to describe the prospect of having someone else govern the Golden State for the next 14 months, after which the Democratic nominee will almost certainly win again.)

The profs continue: "In these times of intense party polarization, we should be wary of mechanisms that enable electoral losers to win back power through outlandish means or to derail the governing agenda of a popularly elected officeholder."

That's one way of looking at it. Another way is to note that polarization has helped produce 30 essentially one-party states, in which the same team controls the governor's mansion, the state legislature, the two U.S. Senate seats, a majority of the House delegation, and a predictable presidential vote. Against that backdrop, recalls could also be interpreted as the last direct-democracy line of citizen self-defense against mono-party hackery.

Unfortunately for Larry Elder—who is only leading the if-Newsom-is-recalled pack because Republicans have precious few California political professionals of note, and Democrats made the conscious choice not to run a viable candidate (recall targets themselves are barred from appearing on Question No. 2)—most journalists and professors swim in the same ideological fishbowl as the state's dominant political party.

That means not only that every micro-blemish stands out—"Before the California recall, Larry Elder's charity failed," panted the L.A. Times, about an Elder nonprofit that in nearly two decades raised all of $20,000—but also that his events are covered in ways inconceivable if he had a different letter beside his name. When a white woman in a gorilla mask threw an egg at Elder (who is black) on a Venice street last week, the news media was uncharacteristically subdued about possible racial subtext.

The op-ed pages have shown no such reticence about divining (negative) racial import from Elder's campaign. Sample headlines: "Larry Elder and the danger of the 'model minority' candidate," "California governor recall hopeful Larry Elder is a soldier for white supremacy," "Larry Elder is the Black face of white supremacy. You've been warned," and "Larry Elder says he's not a face of white supremacy. His fans make it hard to believe." Why, it's enough to make you suspect that there might be dual standards applied to public figures based on their party affiliation!

In a column Monday for Mediaite, California commentator John Ziegler posited that the media imbalance might end up proving decisive for Newsom.

"Given his extreme advantages in voter registration, the power of incumbency, money, and highly favorable media coverage from every single communication outlet except talk radio, it would have taken a near miracle for him to be removed," Ziegler wrote. "But he will get away with claiming vindication for his Covid polices because the news media, which is similarly deeply invested in not having been very wrong for the last year and a half, will be thrilled to share in his alleged exoneration."

I suspect that that's exaggerated, in part because the news media just doesn't have that much popular pull, but we'll see. In the meantime, the elites who use the news media to talk amongst themselves and maybe pry open the Overton window a bit have been making every indication that a post-Newsom recall mechanism will be either mended or ended.

Berkeley law professors Erwin Chemerinsky and Aaron Edlin got the ball rolling one month ago with an unconvincing New York Times argument that the recall was unconstitutional. Straight news pieces have been given headlines like "Has California's unique brand of direct democracy gone too far?" The state Senate last week passed a law banning paid signature-gathering, which would gut California's entire direct-democracy apparatus (and likely invite legal challenges).

Most of the reform proposals being floated would make it more difficult for voters to challenge their leaders. California requires the signatures of 12 percent the number of those who voted in the last relevant election, which is the lowest recall threshold in the country; most are at around 20 percent. "Other states with recall provisions, like Minnesota and Washington, require an act of malfeasance or a conviction for a serious crime for the recall to proceed," The New York Times notes wistfully. (Such designations being too important to leave in the hands of mere voters.) Newsom himself prefers the automatic installation of the lieutenant governor in case of recall, which would in the current electoral climate lock Republicans out of the statehouse.

The catch is that any such change in the state constitution has to be approved…via statewide ballot referendum. Public opinion surveys show that Californians are open to tinkering, but they do appreciate having the recall power.

As do I, though I forfeited the privilege long ago via U-Haul. There is an available if lonely conclusion to be potentially gleaned from today's vote, should Newsom indeed survive: The system maybe…works? Six for 11 in recalls, including one for two with governors, across 98 years does not seem to me evidence of a "dangerous" and "outlandish" anachronism, overrun by "manipulation." Turns out it's actually pretty hard to recall a popularly elected Democrat in a heavily Democratic state, particularly when the minority party is attracted to nutjob candidates and clownball tactics.

Democrats could just take the W, rather than squeeze ever more tightly on power. Which means you can expect to see degrees of recall-difficulty placed on the ballot in time for the midterms.

Show Comments (75)