Canadian Steak Tartare Ban Leaves Chefs Feeling Raw

Warning people about the dangers of raw meat doesn't require prohibiting the practice.

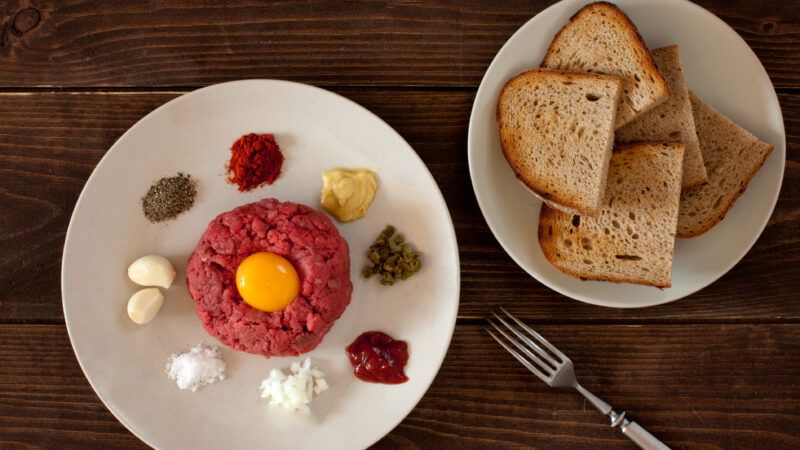

A chef in New Brunswick, Canada, is aghast after learning of his province's ban of steak tartare, a dish he serves to customers that's typically made with raw beef and raw eggs. The ban came as a surprise to Luc Doucet of Black Rabbit in Moncton, one of several restaurateurs warned recently by health department officials that serving raw meat violates provincial health codes.

"Our department was recently made aware that ground beef prepared as per the request of the customer (i.e., medium, rare, etc.) and/or steak tartare, is presently available at your food premises," a health department note to Doucet, included in a CBC report on the ban, declares. "This practice must cease immediately, as it is in direct violation of the New Brunswick Food Regulation, NB Reg 2009-138, 27 1(f) Schedule A."

While the tartare ban came as news to Doucet, non-Canadian readers here may be surprised to learn that preparing anything but well-done hamburgers—"medium, rare, etc."—is banned throughout Canada. In a 2017 column panning this foolhardy prohibition on serving hamburgers that taste like hamburgers, I called that ban "as arbitrary a decision as banning raw animal products such as oysters and sushi, raw produce such as sprouts and melons, and countless other [potentially hazardous] foods that are definitely legal in Canada."

Doucet, whose restaurant was nominated for best new restaurant in Canada in 2019, told the CBC that the "ideology" behind the ban is what bothers him most. That and the vagueness of the notice.

"It's tricky, the wording is very vague, it just says 'beef tartare etcetera,' is that carpaccio [a thinly sliced meat served raw]?" he told the CBC. "I don't know."

Doucet isn't the only one panning the ban. In an editorial published this week, New Brunswick's Telegraph-Journal editorial board urged the province to repeal its tartare ban, which the paper dubbed "baseless." (They really missed an opportunity to use "groundless.")

"Our food safety culture in Canada is overdone and our food appreciation culture is underdone," Telegraph-Journal editor Martin Wightman lamented in a tweet referencing the editorial. Wightman's comment echoes (though is a little more harsh than) my own prior criticism of Canada's food laws.

Though the New Brunswick health department notice Doucet received did reference a hypothetical process for potentially allowing restaurants to serve foods containing raw meat, my email and phone call to the health department spokesman quoted by the CBC, Bruce Macfarlane, were not returned. What's more, since the CBC report indicates the crackdown on steak tartare was not due to any case of foodborne illness, it's not clear why the health department decided this month to set its sights on steak tartare.

It's not Canada's first. In 2012, a restaurant in Windsor, Ontario—just outside Detroit—was targeted by health inspectors for serving lamb tartare and carpaccio. Chef and owner Rino Bortolin fought the ban, telling the CBC he would serve the dishes "until an inspector tells me to stop… And if they tell me to stop, I will probably still do it."

Could New Brunswick chefs meet that province's ban by practicing similar civil disobedience? I hope so.

Canada isn't alone in fretting over raw beef served in restaurants. Beginning in 2007, Slovakia banned restaurants from serving steak tartare, a traditional dish in that country. That ban, which the Slovak Spectator reports was ignored by a number of top restaurants, was repealed in 2017. Though the ban was lifted, restaurants must now warn consumers that consuming raw meat poses risks—a sensible requirement. They also must prepare the dish to order, use eggs only from "approved farms," and inform public health officials that they serve the dish. And health officials in Wisconsin regularly caution residents against eating so-called "cannibal sandwiches"—basically steak tartare on bread—which are a popular homemade food to serve around the holidays.

Experts suggest such fears over eating raw meat may be overblown. For example, after Japan banned serving raw beef liver in 2012 over fears consuming the dish contributed to higher E. coli case numbers, a study found no reduction in E. coli cases since the ban took effect. And Canada's ban on flavorful hamburgers, the National Post reported in 2012, may be unwarranted, as properly cooked (not undercooked) hamburgers "may not be nearly as dangerous as we all thought."

All that said, eating raw meat—just like eating sushi, sprouts, melons, runny eggs, and the like—does occasionally sicken or kill people. In 2014, several people became ill—one critically—after eating steak tartare in a Montreal restaurant. But even after those rare cases, an expert at McGill University responded that "poisoning from steak tartare is rare because the dish is usually served only in high-end restaurants where hygiene is the rule and the meat is supplied by reliable butchers."

Raw beef isn't for everyone. I first tried raw ground beef at an Ethiopian restaurant—where the dish is known as kitfo—in Washington, D.C., in the late 1990s. It was great, and I've enjoyed it several times since. Raw beef not your thing? That's cool. Don't eat it. Please just make sure others can do so if they so choose.

Show Comments (261)