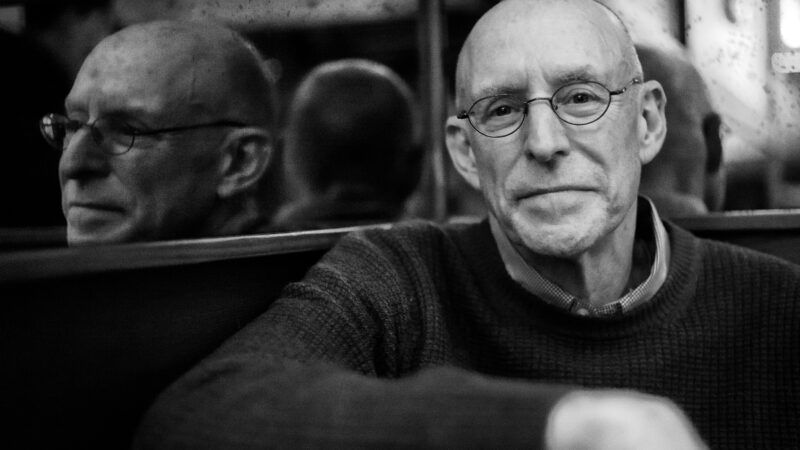

Psychonautical Journalist Michael Pollan Is Finally Ready To End the War on Drugs

The evolution of Pollan's thinking reflects the confusion caused by arbitrary pharmacological distinctions.

Journalist Michael Pollan, author of the 2018 psychedelic history/memoir How To Change Your Mind, seems to have changed his own mind about the best way to address America's unjust and irrational drug laws. The evolution of Pollan's thinking illustrates the arbitrariness of the categories that Americans use to classify intoxicants and the confusion it causes even for well-meaning and thoughtful observers who are sympathetic to drug policy reform.

In a 2019 New York Times opinion piece, Pollan expressed concern about using ballot initiatives to decriminalize or legalize psychedelics, suggesting that we should rely on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to decide who may use which psychoactive substances under what circumstances. "Psilocybin has a lot of potential as medicine," the subhead said, "but we don't know enough about it yet to legalize it."

In a New York Times essay posted this morning, Pollan, whose new book on psychoactive plants was published this week, acknowledges the limitations of treating psilocybin and other psychedelics as medicines and welcomes the success of the ballot initiatives that initially worried him. He also extends his critique of the war on drugs to "hard ones like heroin and cocaine."

There are two main problems with relying on the FDA to decide how drugs should be treated. First, approval of a new medicine takes years and requires spending millions of dollars on clinical studies. Second, the agency's mission is limited to assessing the safety and efficacy of drugs that are presented as a treatment for a recognized medical or psychiatric condition.

The war on weed continued after the FDA approved synthetic THC as a treatment for the side effects of cancer chemotherapy in 1985, after it added AIDS wasting syndrome as a recognized indication in 1992, and after it approved the first federally sanctioned cannabis-derived medicine as a treatment for two rare kinds of epilepsy in 2018. The war on psychedelics likewise will continue after the FDA approves MDMA as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder or psilocybin as a treatment for severe depression. FDA approval means only that patients who have the requisite diagnosis and prescription can legally use substances that are otherwise forbidden. Every other user is still treated as a criminal.

Another "path to normalization" that Pollan discusses is religious exemptions. "Since 1994," he says, "the Native American Church, now with an estimated 250,000 members, has had the constitutional right to use peyote as a sacrament." Pollan is wrong about both the origin and the nature of that exception, and the history of this issue shows that pharmacological freedom for members of one religious group does not necessarily imply a similar tolerance for other sects, let alone Americans generally.

The ceremonial use of peyote by members of the Native American Church has been protected by federal regulation since 1965. That exception was codified in 1994 by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which said "the use, possession, or transportation of peyote by an Indian for bona fide traditional ceremonial purposes in connection with the practice of a traditional Indian religion is lawful, and shall not be prohibited by the United States or any State." Far from establishing a "constitutional right," that law was a response to a Supreme Court decision that said there was no such right.

In the 1990 case Employment Division v. Smith, the Court upheld the denial of unemployment benefits for two drug counselors who had been fired for violating Oregon's drug laws by using peyote in Native American Church ceremonies. Departing from precedent, the justices said the First Amendment's Free Exercise Clause does not require exemptions from neutral, generally applicable laws that impinge on religious conduct. Congress reacted by passing both the American Indian Religious Freedom Act and a broader statute, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which revived the test that the Court had rejected. Under RFRA, the government may not "substantially burden a person's exercise of religion" unless it is using "the least restrictive means" to pursue a "compelling government interest."

In 2006, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that RFRA protected the ceremonial use of ayahuasca by the religious sect Centro Espirita Beneficente União do Vegetal. Eight years later, the Court ruled that RFRA also protected business owners who for religious reasons objected to a federal mandate requiring them to provide their employees with medical insurance that covered 20 specified kinds of contraception. Citing both of those cases, Pollan suggests "this Supreme Court's expansive jurisprudence on religious freedom has created a wide opening through which a parade of new psychedelic churches may be able to march."

Given the skepticism with which federal courts have greeted such claims, I have my doubts. More to the point, RFRA protection is available only to psychedelic users who belong to organized religious groups that describe a particular drug as central to their rituals. What about the rest of us?

Pollan, who in 2019 expressed trepidation about the psilocybin initiative that Oregon voters approved last year, is now more sanguine about that measure, which gave the Oregon Health Authority two years to write rules for licensing and regulating "psilocybin service centers" where adults 21 or older can legally take the drug under the supervision of a "facilitator" after completing a "preparation session." The initiative specifies that regulators "may not require a client to be diagnosed with or have any particular medical condition as a condition to being provided psilocybin services."

Pollan describes this newly permitted drug use as "psilocybin therapy," a hangover from his earlier focus on psychedelics as officially approved medicines. But the significance of Oregon's initiative lies in its departure from the FDA's approach, which allows drug use only by prescription for treatment of a "particular medical condition."

Oregon nevertheless will restrict psilocybin use to licensed, supervised settings, which reassures Pollan. Building on the Oregon model, he imagines "spa-like retreat centers" that would cater to "Americans who want to use psychedelics in a more secular setting." He suggests those services would include a psychiatric screening, administration of psychedelics by "a doctor or nurse practitioner," and supervision by "trained facilitators."

In terms of liberalizing the legal treatment of psychedelics, that is about as far as Pollan seems willing to go. "The prospect of magic mushrooms being commercialized like cannabis—advertised on billboards and sold next to THC gummy bears in dispensaries—should fill us with trepidation," he says. "Microdoses perhaps, but a macrodose of psilocybin is a powerful, consequential and risky experience that demands careful preparation and an experienced sitter or guide."

Keep in mind that Pollan himself has used a wide range of psychedelics, experiences that he describes in How To Change Your Mind. He did that without joining a church, getting permission from a doctor, or visiting a government-licensed "retreat center." And while he says there should be some allowance for "healthy people without a psychiatric diagnosis who want to use psychedelics for therapy, self-discovery or spiritual development," where does that leave people who use psychedelics out of curiosity or just for fun?

Pollan's insistence that would-be psychedelic users demonstrate a serious purpose and comply with regulations that he never followed reflects a disdain for psychonauts who have not written bestselling books about their adventures. While he can be trusted to take appropriate precautions, he thinks, the rest of us need to be constrained by legal rules.

To his credit, however, Pollan has begun to overcome the "psychedelic exceptionalism" that irritates Columbia psychologist Carl Hart, author of Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear. Hart, a temperate heroin user, decries the bigotry of people who see nothing wrong with marijuana or psychedelic use but look down on drug consumers with different pharmacological tastes.

"This is uncomfortable territory, partly because few Americans regard pleasure as a legitimate reason to take drugs and partly because the drug war (with its supporters in academia and the media) has produced such a dense fog of misinformation, especially about addiction," Pollan writes. "Many people (myself included) are surprised to learn that the overwhelming majority of people who take hard drugs do so without becoming addicted. We think of addictiveness as a property of certain chemicals and addiction as a disease that people, in effect, catch from those chemicals, but there is good reason to believe otherwise. Addiction may be less a disease than a symptom—of trauma, social disconnection, depression or economic distress."

Although addiction experts such as Stanton Peele have been making these points for half a century, they apparently were news to Pollan, despite his keen interest in chemically assisted mind alteration. In support of the observation that drugs do not cause addiction, Pollan cites the "Rat Park" experiments that Canadian psychologist Bruce Alexander conducted in the late 1970s, inspired by Peele's 1975 book Love and Addiction (co-authored by Archie Brodsky). Pollan also mentions a classic study of veterans who used heroin in Vietnam that was published in 1974.

Better late than never. The newly enlightened Pollan endorses "harm reduction" measures such as "drug treatment, instead of incarceration," needle exchange, heroin maintenance, and decriminalizing low-level possession (as Oregon voters also did last year). He even broaches the possibility of repealing prohibition, which is where the logic of harm reduction ultimately leads—the reason the concept "terrified drug warriors," as Maia Szalavitz notes in her new history of the movement. Pollan suggests that "the uneasy peace our culture has made with alcohol may point to a way drugs like heroin and cocaine might someday be used in the post-war-on-drugs era." Indeed it might.

"The long history of humans and their mind-altering drugs gives us reason to hope we can negotiate a peace with these powerful substances, imperfect though it may be," Pollan says. "We have done it before. The ancient Greeks grasped the ambiguous, double-edged nature of drugs much better than we do. Their word for them, 'pharmakon,' means both 'medicine' and 'poison'—it all depends, they understood, on use, dose, intention, set and setting. Blessing or curse, which will it be? The answer depends not on law or chemistry so much as on culture, which is to say, on us."

Our disastrous drug control regime is built on pharmacological prejudices that cannot withstand rigorous study or careful thought. Pollan deserves credit for discarding some of his.

Show Comments (35)