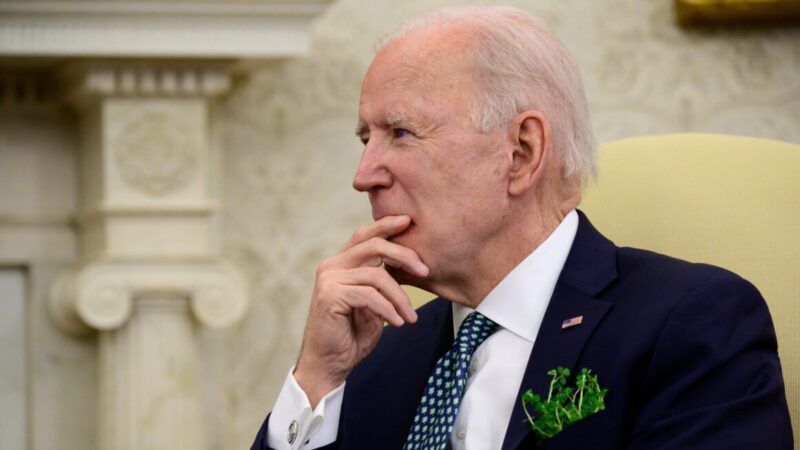

Joe Biden's Fragile Global Minimum Tax Cartel

The Biden administration is expending a lot of time and energy to make the country more uncompetitive than ever.

Governments voice displeasure when large institutions get together to fix prices—except when those institutions are governments colluding on tax rates. Competition might offer the public a range of choices, but politicians want to be able to dictate terms without competing themselves. At the end of the day, that lack of interest in appealing to the public is what's behind the push for an international cartel to impose a global minimum tax.

"By choosing to compete on taxes, we've neglected to compete on the skill of our workers and the strength of our infrastructure," U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen huffed in April. "It's a self-defeating competition, and neither President Biden nor I am interested in participating in it anymore. We want to change the game."

The game-changer the Biden administration has in mind is to raise the corporate tax rate from the current 21 percent to 28 percent. Since the higher rate would be well above the international average, more than triple Switzerland's 8.5 percent, and almost twice the 15 percent charged by Canada (Canadian provinces and Swiss cantons also impose additional taxes, just like U.S. states), that would seem to put the U.S. at a disadvantage relative to other countries. That is, the U.S. would be at a disadvantage unless it could convince other governments to stop competing and fix prices.

"Destructive tax competition will only end when enough major economies stop undercutting one another and agree to a global minimum tax," Yellen added.

Politicians in other industrialized countries also see advantage in cartelizing tax collection. Such a scheme would let them all hike the price of doing business without worrying that international companies would migrate to friendlier tax climates.

"Finance ministers from Group of Seven nations meeting in London on Friday are expected to back President Biden's call for a global minimum tax on corporate profits, giving him an early win in a grueling diplomatic campaign that is just beginning," the Washington Post reported this week.

Sign-off from the Group of Seven means that Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom are on-board with the idea of a floor on tax rates. Finance ministers from wealthy nations delight in the idea of turning profitable international business ventures into a captive herd of milking cows—with the costs inevitably passed on to consumers with equally constrained choices.

But, if governments have been competing on tax rates, somebody must have been benefiting. Companies obviously like lower-tax regimes, but many countries have shouldered their way to prosperity by refraining from mugging successful businesses quite so vigorously as their neighbors.

"In the late Eighties some 1.2 million people worked in the economy, a figure little changed since the foundation of this State in 1922," The Irish Independent editorialized in 2004. "Currently, there are 1.8 million in employment, a 50 per cent increase in less than two decades. This expanded workforce now includes many who have returned from abroad to work here, who were forced to emigrate in the barren Eighties. The Ireland they left behind was a land of high tax, high unemployment, high debt, high emigration, one of low growth, little opportunity, and less hope. Today, one-third of immigrants are returning Irish nationals, and for many the Ireland of their homecoming is unrecognisable from the place they left, not least the low-tax regime that has released energy and enterprise, that has generated self-confidence, created jobs and helped raise living standards."

Ireland dragged itself from poverty by making itself a relatively welcoming place in which to do business. No wonder Paschal Donohoe, the country's finance minister, told global minimum tax fans to pound sand. He says that Ireland will keep its 12.5 percent rate for the foreseeable future.

Other countries saw Ireland's success and emulated it with low tax rates of their own. That's especially true in Eastern European countries that had to hustle to catch up with market-oriented economies after the collapse of Soviet bloc socialism. They, too, are unimpressed by tax cartel schemes.

"All over the world, we're seeing the pursuit of policies that are making it harder to reboot the global economy, such as the ones in favour of introducing a global minimum tax," warns Peter Szijjarto, minister of foreign affairs and trade in Hungary, where the corporate tax rate is 9 percent. "We won't accept any form of international pressure or regulation that would lead to tax increases in Hungary."

If the U.S. and other Group of Seven governments set a minimum tax without buy-in from the likes of Hungary and Ireland, they risk making those low-tax countries more competitive than ever. And those countries have little incentive to join the rush to a tax cartel since they built their prosperity with environments including low rates.

So, White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan may be a little premature when he boasts that "[t]he world is closer than ever before to a global minimum tax." That's true only if you define the world as developed economies that don't feel a need to offer attractive environments but would rather sit back and milk the herd.

True, many of the low-rate countries are small nations, potentially vulnerable to pressure or bribery from their larger neighbors. But these countries are already at odds with wealthy nations over other taxes and, in the case of Hungary, sometimes illiberal domestic policies. New friction might just prompt them to go their own way. Beyond those countries is an entire world trying to attract business and often resistant to arm-twisting.

"Along with opposition from corporate lobbyists, additional obstacles loom, including objections from low-tax countries such as Ireland as well as likely noncompliance from China and Russia," the Washington Post noted. "After more than three decades of factory offshoring, any global minimum levy also might only minimally reshape the map of global production and investment."

Perhaps recognizing that reality, the Biden administration dropped its target global minimum tax rate from 21 percent to 15 percent. That's likely to draw less opposition from competing governments, but it widens the gap between a global rate and the 28 percent with which the administration wants to sock American companies.

Ultimately, the U.S. government appears to be expending a lot of time and energy to set up a fragile tax cartel that leaves the country more uncompetitive than ever.

Show Comments (102)