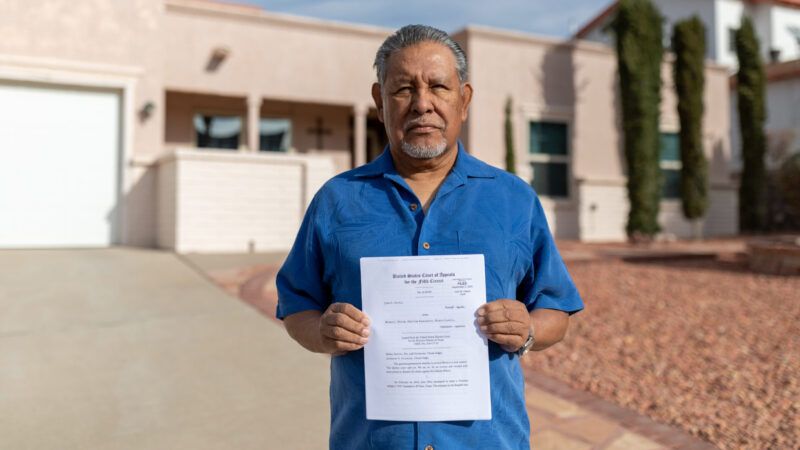

Federal Cops Attacked a 70-Year-Old Vietnam Veteran and Then Avoided Accountability in Court

The Supreme Court declines to hear arguments in Oliva v. Nivar.

In September 2020, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit dismissed a federal civil rights lawsuit filed by José Oliva, an elderly Vietnam veteran who was beaten and left permanently injured by federal police at a Department of Veterans Affairs (V.A.) hospital in El Paso, Texas. According to Oliva, the V.A. cops targeted him for abuse after he failed to promptly show his ID, which was temporarily out of reach in a metal detector bin.

"I got a problem with this man," one of the officers reportedly said about Oliva's supposed lack of cooperation. "He's got an attitude." The same officer then placed the 70-year-old in a chokehold and slammed him to the ground, permanently injuring Oliva's shoulder.

Oliva's lawsuit alleged that the unprovoked attack violated his Fourth Amendment rights. But the 5th Circuit waved those constitutional concerns away, holding that U.S. Supreme Court case law effectively shielded the federal cops from facing any such civil accountability.

Today, Oliva received another undeserved injury, this time at the hands of the Supreme Court itself. In an unsigned order issued this morning, the Court declined to hear Oliva's appeal. The 5th Circuit's ruling in Oliva v. Nivar will remain in place.

Much of this regrettable legal saga is the direct fault of the Supreme Court. In Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (1971), the Court held that the federal drug cops who entered Webster Bivens' apartment without a warrant, rifled through his belongings, shackled him in front of his family, and later strip-searched him at the federal courthouse, could be sued for violating Bivens' Fourth Amendment rights. But as 5th Circuit Judge Don Willett protested in a recent opinion, the Supreme Court has since weakened its Bivens precedent to such an extent that "if you wear a federal badge, you can inflict excessive force on someone with little fear of liability."

The 2017 case of Ziglar v. Abbasi illustrates exactly how the Court undermined its previous holding. If a Bivens suit against an allegedly unlawful federal officer arises in "a new context," the Court said in Ziglar—meaning "the case is different in a meaningful way from previous Bivens cases decided by this Court"—then the presiding judge should look for any "special factors counseling hesitation." As soon as any such "special factor" is found (or cooked up), then the lawsuit must be dismissed.

Three years later, in Hernandez v. Mesa (2020), the Court doubled down on that approach. "If we have reason to pause before applying Bivens in a new context or to a new class of defendants," the Court said, "we reject the request." As the Court declared in Ziglar, "the Bivens remedy is now a 'disfavored' judicial activity."

José Oliva filed a Bivens claim against the V.A. cops who attacked him. But the 5th Circuit, taking its cues from Supreme Court, dismissed his suit as "a new context" because "this case differs from Bivens in several meaningful ways." For instance, the appeals court maintained, "the case arose in a government hospital, not a private home." Also, "the VA officers were manning a metal detector, not making a warrantless search for narcotics."

The end result of that SCOTUS-sanctioned legal quibbling: The V.A. cops who beat an elderly veteran got to avoid accountability in civil court.

Show Comments (43)