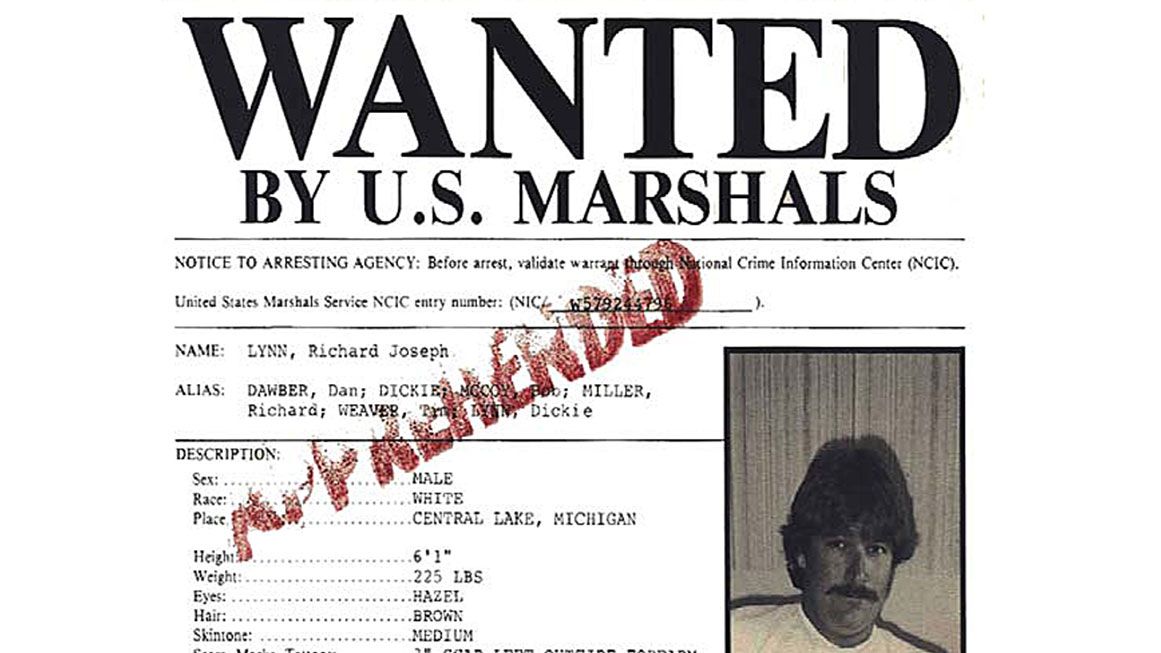

This Florida Drug Smuggler Escaped 7 Life Sentences—Twice

Dickie Lynn's story shows how the drug war warped the criminal justice system.

For a long time, Richard "Dickie" Lynn didn't think he'd ever see the mesmerizing blue waters of the Florida Keys again.

The former drug smuggler and onetime escapee from federal prison had received seven life sentences after he was convicted as part of a massive 1989 drug trafficking sting. He was released last June after serving 31 years.

I caught up with Lynn, 66, a few months after his release. Today, he sports a mop of light brown hair and a graying goatee. He's back in his element, wearing the typical Keys uniform: performance fishing shirt, shorts, and flip-flops.

I wanted to talk to him not only because his story is a wild true crime tale involving Cuban dissidents, former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, and corrupt Customs agents. I wanted to talk to him because the prosecution, incarceration, and improbable release of Dickie Lynn shows how the drug war warped the criminal justice system, and how the country has slowly tried to fix it.

From the harsh sentences of the 1980s to the criminal justice reform movement of the 2010s, Lynn experienced it all. His life story is also the tale of four decades of the U.S. criminal justice system—its failures and flaws, and its recent turn toward redemption.

Florida Man Has Fast Boat, Drug Smuggling Business

Lynn grew up in the Florida Keys, the chain of small islands that runs past the tip of mainland Florida for 125 miles, terminating in Key West. The area has been a smuggler's paradise for as long as there's been contraband to smuggle. The Keys backcountry is dotted with hundreds of small, uninhabited islands and twisting mangrove channels. It's close enough to get to Cuba or the Bahamas by boat, South America by plane, and Miami by road, making it an ideal stopover for inbound drugs.

Longtime Keys residents will tell you about taking Jon boats out as teenagers to look for "square grouper"—a joke term for the stray bales of dope that sometimes drifted into the mangroves after drug runners threw them overboard while fleeing the Coast Guard and other authorities. Locals like Lynn soon discovered there was an obscene amount of money to be made using their knowledge of the local waters to run pot.

Back then, the tools of the trade were a fast boat, steady nerves, a friend with a radio scanner to keep an eye on military and law enforcement chatter, and a roll of quarters for the pay phones.

"You know when Jimmy Buffett says, 'Rule my world from a pay phone'?" Lynn asks, referring to a line from the song "One Particular Harbor." "That's what it was."

Federal prosecutors estimated that one of the largest marijuana trafficking rings in South Florida grossed $300 million between 1977 and 1981. One pilot from the era estimated he made $750,000 to $1 million over two years just smuggling pot. The amount of money that was flowing into the local economy meant no one was complaining too much, either.

"If they weren't smuggling with us or working on our boats, we were building houses or lending them money to start a restaurant," Lynn says. "Mothers used to sit around and listen to scanners in case somebody was throwing something off the boat or whatever."

Key West was so corrupt that a 1975 state and federal crackdown on the tight-knit network of local drug traffickers netted, among others, the city attorney and the fire chief, Joseph "Bum" Farto. Farto disappeared in 1976 while awaiting sentencing. He told his wife he was driving up to Miami for the day and was never seen again. The question "Where is Bum Farto?" has haunted Key West ever since.

As marijuana gave way to cocaine in the late '70s, the potential risks and rewards of smuggling exponentially increased. Lynn and a small crew upgraded from airdrops and runs of pot from Jamaica and the Bahamas to running flights of cocaine from South America to rural Alabama, where they operated out of a remote hunting camp.

According to Apprehended: The Trials of Dickie Lynn—a 2013 book by Domingo Soto, one of the defense attorneys in Lynn's case—the pilots would take off from South Florida, fly to Colombia, and load up the plane with duffel bags full of cocaine. The pilots would then fly to Belize and land on a road cutting through a sugar cane field, where they would hand the locals $50,000 in cash in exchange for a refuel and a bag of fried chicken. After taking off again, they'd head back across the Caribbean toward the Gulf Coast.

At about 125 miles south of the coast, the pilots would drop their altitude and cut their speed, hoping to appear on radars like one of the helicopters that shuttles back and forth from offshore oil rigs. Lynn was responsible for the ground crew in Alabama, which would meet the plane at one of the lightly used airstrips nearby, offload the coke, and get the plane back in the air as quickly as possible.

A series of mishaps set the smuggling ring's downfall in motion. In 1986, the pilots had to abandon an entire load of drugs at a small airport in Mississippi because their intended airstrip was covered in fog. The unexpected appearance of 700 kilograms of cocaine did not go unnoticed by local and federal law enforcement. The Jackson Clarion-Ledger declared it "the largest load of cocaine ever seized in Mississippi," though the use of "seized" was a rather generous characterization of the role of law enforcement.

A year later, one of their planes exploded while trying to land on a foggy night, killing the two pilots. Law enforcement discovered a crash site strewn with hundreds of bundles of cocaine.

Finally, in 1988, police responded to a report of unusual lights at a small airstrip in Perry County, Alabama. They arrived just as the smuggling ring's Cessna 404 Titan finished refueling. The pilot flipped on all the lights and sped down the runway at the advancing police cruisers, playing a game of chicken. The cruisers swerved, and the plane took off into the night, while the ground crew disappeared into the surrounding forest.

The escape was short-lived. Authorities caught up with the pilots in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Investigators had been piecing together information on the planes and their owners for several years. Both pilots flipped in exchange for immunity, agreeing to wear wires to further implicate others in the smuggling ring.

Jeff Sessions Offers Life in Prison

In 1989, the Justice Department indicted Lynn and 21 others in a sprawling drug trafficking investigation. The indictments included four U.S. Customs agents who were on the take.

One of those agents was Charlie Jordan, the marine enforcement station chief in Key Largo and self-declared "ruler of the Florida Keys." Jordan had gone on the lam two years earlier after he was indicted on other charges, leading to an appearance on America's Most Wanted and a nationwide manhunt that ended with his surrender in Wyoming.

Two of the organizers of the smuggling operation were Cuban dissidents Andy and Fernando Pruna. Fernando was a counterrevolutionary who had spent 17 years in one of Fidel Castro's prisons. Andy was among the small team of frogmen—underwater demolitions specialists—who were the first to hit the beach in the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion.

Rural Alabama might have seemed like an ideal choice for an out-of-the-way smuggling camp, but unfortunately for Lynn and the rest, it landed them in the jurisdiction of the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of Alabama, which at the time was run by a zealous federal prosecutor named Jeff Sessions.

Sessions would go on to represent Alabama in the U.S. Senate, where he earned a reputation as one of Congress' staunchest defenders of the drug war and mandatory minimum sentences.

"The only offer I ever got from Jeff Sessions was a life sentence," Lynn says. "And if you're offered a life sentence, you're going to go to trial."

At trial, Lynn was convicted on seven counts of conspiracy to import and distribute marijuana and cocaine. He managed to beat the most serious charge of being a leader or organizer of the drug trafficking organization under the Continuing Criminal Enterprise statute, also known as the "kingpin" statute. ("I was just acting as UPS," Lynn says. "I was point A to point B.")

But the judge used what's known as "acquitted conduct" to enhance Lynn's sentence. Although a jury declined to find Lynn guilty of being a leader or organizer, the judge used the charge to add four points to Lynn's score under the federal sentencing guidelines anyway. Lynn's offense level was increased by two levels for possession of a firearm during commission of the offense, which he was also never convicted of; four levels for his supposed role as a leader; and two levels for obstruction of justice.

The use of acquitted conduct in sentencing strikes many as antithetical to the principles of the U.S. justice system. Sens. Dick Durbin (D–Ill.) and Chuck Grassley (R–Iowa) introduced a bill last year that would ban the use of acquitted conduct at sentencing. "That's not acceptable, and it's not American," Grassley has said of the practice. But the legislation went nowhere.

Of the 21 co-defendants in the drug conspiracy, Lynn was the only one who was sentenced to life—seven concurrent life sentences, in fact, thanks to a stiff sentencing recommendation from Sessions' office.

Lynn was looking at a bleak future of life and death behind bars without the possibility of early release. Federal parole was abolished in 1987 as a result of the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, a bill spearheaded by then–Sens. Strom Thurmond (R–S.C.) and Joe Biden (D–Del.), who would go on to spend the 2020 Democratic primary and general election running away from his criminal justice record. In addition to getting rid of parole, the bill created the U.S. Sentencing Commission and the federal sentencing guidelines, ushering in the current era of determinate sentencing.

Supporters of the legislation—and there wasn't much -opposition to speak of—hoped the guidelines would impose uniformity and end the wild disparities in sentencing that could occur for identical crimes from judge to judge and district to district. But reducing the discretion of judges gave more of it to prosecutors in the plea bargain process, especially when combined with the mandatory minimum sentences that Congress also created. That's how Sessions' office could confidently offer Lynn a take-it-or-leave-it "deal" of life in prison for violating the kingpin statute.

"The guidelines had just come in, and they were blowing people up left and right," Soto recalls. "Over time, reality has started to sink in that you just can't warehouse people for 30 years, but in '89 the rules were brand new, so he got hit pretty hard."

Without hope of parole, Lynn filed an appeal of his conviction. While it was pending, he decided to pursue an extrajudicial solution to his predicament.

A Daring Escape Makes a Prisoner Into a Fugitive

In February 1990, a couple of months after his sentencing, Lynn was incarcerated at a federal prison in Talladega, Alabama, working in the kitchen, when he noticed the truck that delivered produce was similar to one that he had once used to smuggle marijuana. From inside prison, Lynn and another inmate arranged the purchase of an identical truck. Their outside contact installed a false wall in the back of the trailer with 22 inches of room behind it and a trap door that the two could crawl through. They also smuggled out a copy of a bill of lading—a receipt of service from the produce carrier.

On the day of their escape, the other inmate's father called the produce company pretending to be a prison official. He said one of the prison's coolers was broken and that they should cancel that day's delivery. Meanwhile, the fake truck, complete with identical company markings and a legitimate-looking bill of lading, came and dropped off the produce. Lynn and his buddy waited for an opportune moment, shimmied underneath the truck and into the hidden compartment, and off they went.

Lynn was on the run for nearly six months before the U.S. marshals caught up with him in a restaurant in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, putting together more drug deals. As Lynn bolted from the restaurant, the marshals unloaded what the Associated Press described as a "flurry of gunfire." Neither Lynn nor any innocent bystanders were hit, and Lynn quickly surrendered.

"They said [my escape] was pretty slick, but they sure burned my ass up for it for many, many years, man," Lynn says. "They made me pay for that one."

Because he had escaped custody, a judge dismissed his pending appeal under the "fugitive disentitlement doctrine," which bars fugitives from availing themselves of a justice system they have absconded from. The doctrine dates back to 1876, when the Supreme Court dismissed an appeal of a conviction after the appellant fled. Essentially, it says that those who have escaped the law lose their right to any pending appeal of their convictions.

Meanwhile, in 1991, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit reversed the convictions of two of Lynn's co-defendants because the federal prosecutor in their case had improperly vouched for a government witness who perjured himself at the trial. (About a month after the convictions were vacated, the prosecutor, Gloria Bedwell, was awarded the Justice Department's Exceptional Service Award, presented by then–Attorney General William Barr.)

Back in prison—this time at a high-security penitentiary—Lynn continued to file fruitless appeals as the years dragged on. Congress eliminated Pell grants for federal inmates in 1994, leaving incarcerated people with even fewer ways to try to improve themselves or pass the time.

In 2000, the Supreme Court ruled in Apprendi v. New Jersey that judges were prohibited from enhancing sentences beyond the statutory maximum based on facts other than those decided by a jury, excepting only the fact of a previous conviction. And in 2005, the Court held in United States v. Booker that the Apprendi rule applied to the federal sentencing guidelines. However, neither of those rulings directly touched judges' ability to use relevant conduct at sentencing. In 2014, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by the odd couple of Justices Clarence Thomas and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, urged the Court to address judicial fact finding and the conflicts it raises with the Fifth and Sixth Amendments. In 2015, Brett Kavanaugh, then a judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, wrote that the use of acquitted conduct "seems a dubious infringement of the rights to due process and to a jury trial."

The Clemency Movement

A funny thing started to happen, though. A nationwide movement was growing around the issue of drug sentencing and mandatory minimums.

One of the advocacy groups that sprung up was CAN-DO Clemency, an organization that highlights outrageous mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders. It was founded by Amy Povah, who had herself been imprisoned for nine years of a 24-year drug conspiracy sentence before it was commuted in 2000.

Povah heard about Lynn through several other inmates who were serving life sentences for marijuana offenses. Although his case was not perfect from a public relations standpoint, Povah decided to take it on.

"I empathize with people in Dickie's situation, because I personally used to fantasize about trying to escape," Povah says. "You can't help it when you're in prison, especially when you feel like you've been subjected to a draconian sentence, such as life without parole or multiple life sentences. What choices do you have?"

Lynn applied for clemency during the Clinton and Obama administrations, but such petitions are typically routed through the Justice Department's Office of the Pardon Attorney, which solicits feedback from the very federal prosecutors who secured the sentences in question. One current goal of criminal justice advocates is to remove the Justice Department from the pardon process, arguing it's inherently biased against petitioners.

The U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of Alabama had not forgotten about Lynn and did not empathize with him. His clemency applications went nowhere.

When Donald Trump became president and appointed Sessions attorney general in 2017, Lynn assumed the final door had closed on him. "When I heard that," he says, "I was thinking, 'Well, there goes any chance of getting a commutation or a pardon or anything—that's going to be out the window.'"

But Lynn's hometown of Islamorada had not forgotten him either. Lynn was, if not a hometown hero, at least a missed son. Plenty of others had done the same thing or benefited from it during the heyday of drug smuggling in the Keys, but almost all of them were free. In fact, by 2018, Lynn was the last of the co-defendants in his case that was still behind bars. Jordan, the corrupt Customs agent, was released in 1995. Andy and Fernando Pruna—the latter of whom had fled to Argentina before being extradited back to the U.S.—received substantial sentencing reductions for cooperating and were released in 1994 and 1996, respectively.

The five-member Islamorada Village Council voted in late 2018 to send a letter to Trump pleading for Lynn's release. Among those who thought Lynn deserved to be free was Councilman Ken Davis, a former Coast Guard and Drug Enforcement Administration agent.

"I was here to catch Dickie Lynn," Davis told the Miami Herald. "Now, I'm taking phone calls from him." Davis was laying it on a little thick. He had never personally chased Lynn. Or at least, Lynn says, "I never saw him in my wake."

"To be honest with you, we really didn't get chased much," Lynn says. "When I smuggled marijuana in the Keys, I never got busted for it because there were too many people doing it and it was too easy. The police were on the payroll. The Coast Guard was on the payroll. Customs was on the payroll. Who's going to catch you? The only thing that they'd catch was maybe a truck going up the road with something in it. I mean, they didn't catch me with one gram of cocaine. It was all ghost dope."

"Ghost dope" refers to drugs that were never seized but whose existence was established in court through the statements and testimonies of cooperating witnesses. The estimated amount is then used at sentencing, so even a relatively minor player in a drug ring can get hammered because of the total amount involved in the conspiracy. In Lynn's case, the pilots testified that they were smuggling at least 600 kilograms of cocaine per flight. The government estimated that the group imported nearly 4 tons of cocaine and more than 35 tons of marijuana into South Florida between 1984 and 1988. There was also the very corporeal cocaine the police found in Mississippi and at the crash in Alabama.

Davis also claimed that Lynn's cooperation with federal authorities after he was recaptured helped the U.S. government nab "two of the biggest world cocaine kingpins there were" but says that Sessions' office had torpedoed other federal prosecutors' efforts to get Lynn's sentence reduced in exchange.

Unfortunately, what sounded like good publicity on the outside caused Lynn a considerable amount of consternation in prison. Lynn says he had to set up a phone call between Davis and a "shot caller"—prison slang for a gang leader—so Davis could assure the shot caller that Lynn was not a snitch.

Compassionate Release

In late 2018, Lynn got another shot at freedom when Congress passed the FIRST STEP Act, a modest criminal justice reform bill that still managed to be the most significant action Congress had taken on the issue in more than a decade. The legislation mostly focused on reentry and job training for federal inmates. It also reduced several mandatory minimum sentences and retroactively reduced the notorious sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine, which resulted in the release of about 3,000 federal inmates serving draconian sentences for nonviolent drug crimes.

Most important for Lynn, the legislation allowed federal inmates to petition judges directly for compassionate release, a policy that allows those who are terminally ill or have debilitating conditions the small mercy of dying at home. Previously, inmates could only petition the Bureau of Prisons, which was notorious for its apathy and denial of requests. A 2018 report by the criminal justice advocacy group FAMM found that 81 federal inmates had died since 2014 while their compassionate release petitions were still pending.

After nearly 30 years in prison, Lynn's health had deteriorated. He had heart disease, among other issues. His first petition for compassionate release was denied. But when the COVID-19 pandemic swept through prisons this spring and summer, it also opened up a rare escape hatch for older federal inmates. Barr, who was back at the top of the Department of Justice, issued a directive on March 26 expanding compassionate release and home confinement transfers of elderly and at-risk inmates. Thousands of inmates filed compassionate release petitions arguing that their underlying health conditions and age made them especially vulnerable to the virus.

Meanwhile, local news stories about efforts to get Lynn out of prison caught the attention of Katie Tinto, a clinical law professor at the University of California, Irvine who was assisting eligible inmates with their compassionate release petitions. Tinto and two of her students decided to help Lynn try again.

Included with Lynn's new petition were numerous statements and letters from his supporters, including Edward Odom, the former Alabama state trooper who had launched the investigation into the smuggling ring and eventually arrested Lynn in 1989. "I fully believe that Mr. Lynn has paid his debt to society, and truly deserves some relief," Odom wrote.

On June 15, a federal judge granted Lynn's petition for compassionate release over the objections of the Bureau of Prisons and federal prosecutors. The judge found that Lynn's hypertension, heart disease, and kidney disease—as well as his age and 26-year spotless disciplinary record—qualified as "extraordinary and compelling" reasons for his release.

Lynn's supporters back in the Florida Keys knew about the order before he did. Lynn says he was in his cell when a case manager showed up, asked Lynn his name and ID number, and said to come with him.

Lynn started to put on his shoes, but the case manager told him not to bother. Lynn couldn't read the case manager's face because of his mask. He assumed he was being put in solitary confinement.

As they walked through the prison unit's day room, empty because of the COVID-related lockdown, the manager asked Lynn if he believed in God. Lynn responded, "Absolutely."

In the manager's office, Lynn finally asked what this was all about. "He pulls his mask off, and he's got this big, shit-eating grin on his face," Lynn recalls. "And he goes, 'This is what I enjoy about this job. I don't get to do this very often.'"

The manager handed the phone to Lynn. On the other end of the line was Tinto, who told Lynn that his petition had been granted.

On June 29, 2020—31 years after he last left—Lynn crossed over the sky-blue bridge that marks the end of the Everglades and the beginning of the Florida Keys. Family, friends, and long-time supporters, including Povah, threw him a surprise party, complete with a pile of gifts for all the Christmases he'd missed.

"It's a very wonderful experience to have advocated for some-body, especially with a life sentence and a complicated case, and see him walk out," Povah says. "He's loved by so many people."

Since his release, Lynn has met several of his grandchildren for the first time. He also got to hug one of his old friends from prison, John Bolen—another Floridian who got wrapped up in a drug trafficking conspiracy—after Trump commuted Bolen's life sentence in October. Lynn and Bolen are part of a mercifully shrinking class of nonviolent drug offenders who were sentenced to life, but there are still many more like them left behind.

Lynn still spends a lot of days out on the water. Scrolling through his phone, he shows me pictures of the snook, snapper, and lobsters he's bagged recently.

Like everything else, the Keys have changed a lot in the three decades Lynn was incarcerated. Boaters still occasionally come across floating bundles of drugs, but the days of the cocaine cowboys are over. Margaritaville is a Key West resort now, not just a state of mind. The traffic on U.S. 1 is bad, and the once-sleepy fishing villages have been built out to capacity.

But the Keys themselves—the meager, rocky islands—are the worst part of the Florida Keys. It's the water that captivates people, and to live in the Keys you must love the ocean.

"As chaotic as this place is now, when you get out on the water, it's all the same," Lynn says. "It's beautiful out there still. They can't really mess that up."

Show Comments (34)