California's YIMBYs Forgo Big State Upzoning Bill In Favor of Wonkier, More Modest Reforms

New bills in the legislature would make it easier for cities to allow more housing on their own, and crack down on places that try to cheat their way out of permitting development.

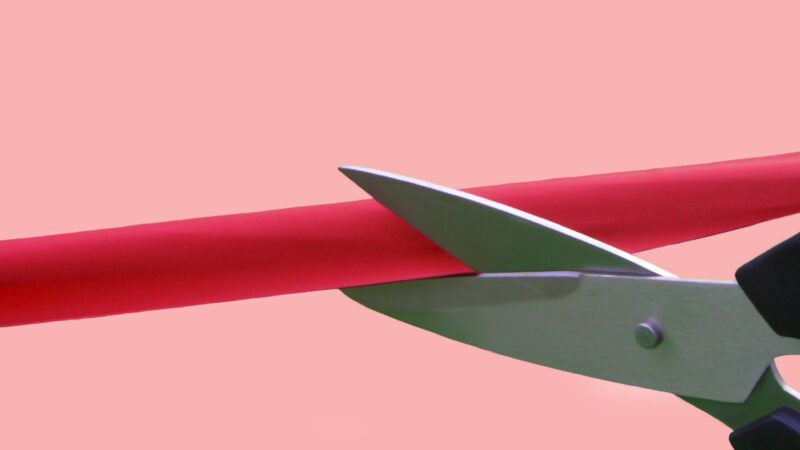

It's housing legislation season in California, where state lawmakers have introduced a flurry of red-tape-slashing bills aimed at kickstarting new development.

"California's severe housing shortage—in the millions—is severely harming our state, and we must take firm actions to help create more housing," said state Sen. Scott Wiener (D–San Francisco). "We need multiple strategies to help end our housing shortage, including empowering cities to build more housing, funding affordable housing, and ensuring that cities are taking necessary steps to meet their housing goals."

The headline-grabbing housing fights of the past three years have been over ambitious, ultimately failed bills co-authored by Wiener, first S.B. 827 and then S.B. 50, that would have preempted local restrictions to allow mid-rise apartments near transit and fourplexes almost everywhere else.

This time, "yes in my backyard" (YIMBY) lawmakers and activists are instead focusing on more modest, wonkier bills that would collect data on the effect of past reforms, pare back more obscure regulations, and make it easier for local governments to ditch their own restrictions on new housing.

One of these bills, S.B. 10, would let cities skip time-consuming, resource-intensive environmental reviews normally mandated by state law when zoning for "missing middle" housing of up to 10 units in areas with lots of jobs or frequent public transit service.

Those environmental reviews can take years and cost millions of dollars. Worse still, the process allows third parties—whether they're neighborhood groups, labor unions, or individual gadflies—to sue if they think a proposed rezoning's environmental impacts weren't studied thoroughly enough, which can hold things up for even longer.

"We're talking about more light-touch density. You can make a real argument that that kind of housing does not need the same kind of environmental scrutiny," Wiener told Reason in January. "It allows cities to do what they want to do, or need to do, quickly and not have to spend ten years doing [environmental impact reports] and getting sued."

Last month, the Sacramento City Council unanimously approved a draft plan to allow up to four-unit homes in all residential areas currently zoned for single-family housing. Local officials in San Francisco and Berkeley have proposed similar ideas.

Should S.B. 10 pass, it could make it easier for these cities to finalize rezonings without having to spend years conducting environmental reviews and fending off lawsuits.

The bill passed rapidly through the state Senate last year, but failed in the state Assembly over what Wiener says were bad inter-chamber dynamics that had little to do with policy. He's optimistic about S.B. 10's changes this year, noting that even some legislators who were skeptical of the state preemptions in bills like S.B. 50 supported it because it gave cities more flexibility.

While that bill would make it easier for cities to allow housing, another of Wiener's proposals would make it harder for them to get away with preventing new housing development.

That bill, S.B. 478, would require localities to allow a floor area ratio (FAR), the ratio of developed floor space to the plot it's built on, of a least 1.5 on residential land zoned for housing developments of two to ten units. This is to combat a devious tactic used by cities whereby they upzone land on paper, but effectively prevent denser development by imposing tight FAR regulations.

The bill would also cap localities' minimum lot size requirements, which often require developers to use more land than they otherwise would, limiting density and driving up prices.

The importance of both pieces of legislation is highlighted by California's ongoing Regional Housing Needs Adjustment (RHNA) process, whereby the state requires regions and localities to plan for enough housing to meet projected future needs.

In 2020, the California Department of Housing and Community Development came out with planning quotas that will require cities and counties across the state to allow a lot more housing than they currently do.

A bill like S.B. 10 will make life easier for local governments by streamlining the rezonings they'll have to do to comply with new, higher RHNA quotas. S.B. 478 will make it harder for local governments to cheat on those quotas by upzoning in theory but still leaving in place development-killing regulations.

"A lot of cities are already saying we have enough capacity. We don't have to change our zoning. If you look carefully at the rules and regulations it's really not true," says Sonja Trauss, the executive director of YIMBY Law. "When you look at the setback requirements and the open space requirements, by the time you go through every regulation, you can't really build ten units there, you can only build two."

The other two bills in Wiener's housing package include one that would spend $100 million on housing for at-risk youth, and another that would have the state collect more data on the effects of past housing laws.

California regulated its way into having the highest rents and home prices in the country. Undoing that bureaucratic detritus requires reformers to propose some regulatory minutiae of their own.

Rent Free is a weekly newsletter from Christian Britschgi on urbanism and the fight for less regulation, more housing, more property rights, and more freedom in America's cities.

Show Comments (22)