The Case Against Julian Assange Is Also a Case Against a Free Press

Contrary to what the judge who blocked his extradition implied, the Espionage Act does not include an exception for "responsible" journalism.

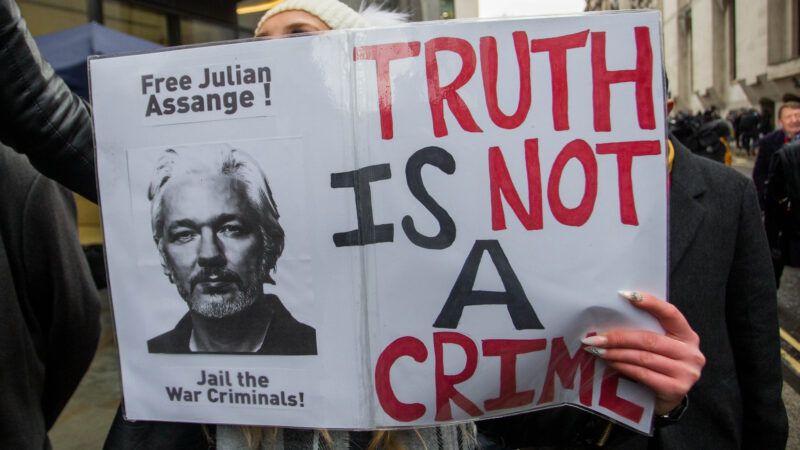

The British judge who blocked Julian Assange's extradition to the United States on Monday was persuaded by psychiatric testimony indicating a "substantial risk" that the WikiLeaks founder would kill himself in response to the harsh conditions he is apt to face in U.S. custody. Although she was much less impressed by the argument that Assange's prosecution for violating the Espionage Act threatens freedom of the press, that danger is just as real.

Westminster Magistrates' Court Judge Vanessa Baraitser accepted the Justice Department's assurance that imprisoning someone for publishing information the government does not want the public to see is consistent with freedom of expression. She emphasized that Assange is accused of posting unexpurgated documents without regard to the danger that could pose to U.S. informants in Afghanistan.

According to the Justice Department, Baraitser noted, "the prosecution case is expressly brought on the basis that Mr. Assange disclosed materials that no responsible journalist or publisher would have disclosed." But the Espionage Act charges against Assange require no such "basis," and any journalist who obtains or publishes classified information related to national security could face the same charges.

The 18-count Assange indictment, which the Justice Department unveiled in May 2019, is based on his disclosure of Defense Department files and State Department cables that indisputably touched upon matters of legitimate public interest, including the treatment of Guantanamo Bay detainees, secret missile attacks in Yemen, and potential war crimes in Iraq. The revelations in these documents generated massive press coverage by leading news outlets such as The New York Times and The Washington Post.

Baraitser, following the Justice Department's lead, wants to distinguish between "responsible" journalism like that and the less careful and professional kind practiced by Assange. But the Espionage Act draws no such distinction.

Counts 9 through 17 of the Assange indictment involve "disclosure of national defense information," a felony punishable by up to 10 years in prison. That penalty applies to anyone who "willfully communicates, delivers, transmits or causes to be communicated" such information to "any person not entitled to receive it."

This felony is the bread and butter of any journalist who covers national security issues and publishes information that the government would prefer to keep secret. So is the conduct described in Count 1, which alleges that Assange conspired to receive national defense information, and Counts 2 through 8, which allege that he obtained it.

Anyone who violates those provisions also faces a maximum sentence of 10 years for each count. So even leaving aside the charge that Assange violated the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act by helping his source, former Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning, crack a password, Assange faces up to 170 years in prison for doing things that respectable news organizations routinely do.

"The New York Times, among many other news organizations, obtained precisely the same archives of documents from WikiLeaks, without authorization from the government—the act that most of the charges addressed," Times national security reporter Charlie Savage noted in 2019. "While The Times did take steps to withhold the names of informants in the subset of the files it published, it is not clear how that is legally different from publishing other classified information."

Responding to Baraitser's decision, Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, warned that "the U.S. indictment of Assange will continue to cast a dark shadow over investigative journalism." In particular, he said, the nine counts focused on "pure publication" represent "an unprecedented attack on press freedom, one calculated to deter journalists and publishers from exercising rights that the First Amendment should be understood to protect."

Assange is not popular with professional journalists, especially since his involvement in publishing the emails that embarrassed Hillary Clinton during the 2016 presidential election. But by now they should realize that the case against him is also a case against them, and they cannot count on their press passes to save them.

© Copyright 2021 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

Show Comments (30)