U.K. Judge Rejects Assange Extradition, but It's No Win for Freedom of the Press

The fear that harsh federal jail conditions will lead to Assange’s suicide is the only reason he won’t face espionage charges in the U.S.

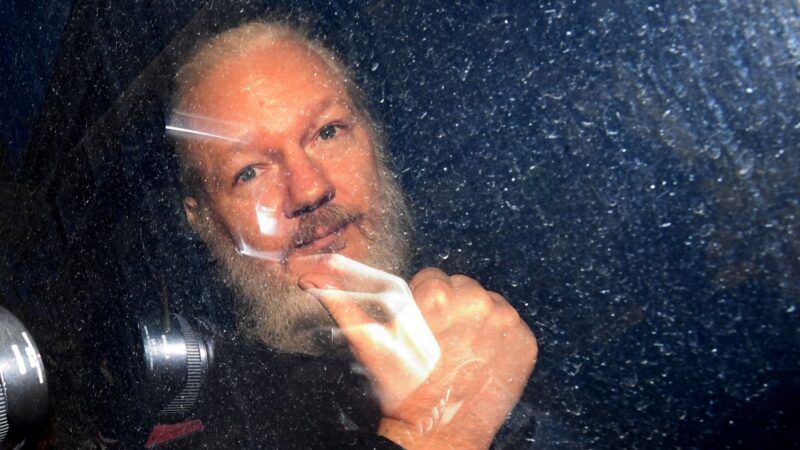

Today a United Kingdom judge denied a United States request to extradite WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange to face conspiracy and espionage charges for publishing secret Iraq and Afghanistan war documents.

Unfortunately, the judge's explanation is not the victory for press freedom that it should be. It's instead rooted in concerns that the harshness of America's prison system might drive a mentally ailing Assange to commit suicide while in detention.

Assange, for his role in encouraging Chelsea Manning to leak military and intelligence documents back in 2009 and 2010, was indicted in 2019 on 18 charges of espionage and additional charges of violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act by giving Manning some minor suggestions on how to crack a password.

The decision to prosecute Assange for his role in publishing classified information crossed a critical threshold—never before had a media figure or journalist been charged with espionage for such an act. Leakers themselves have certainly been charged and have served prison time. But until Assange, the Department of Justice had not charged those who had published the classified information with crimes.

As such, a number of journalists (including many of us here at Reason) and organizations representing journalists have been critical of the charges against Assange. During the extradition hearings, Assange's lawyers brought forth media experts to argue that what Assange had been doing is normal and widely permitted behavior by journalists and that the public had the right to know the information that he published.

The judge, Vanessa Baraitser of Westminster Magistrates' Court, ultimately agreed with the Justice Department's arguments that Assange's actions went above and beyond journalism and into the realm of criminal conspiracy, looking not just at U.S. law, but British and European Union precedents determining when press freedom may be constrained:

The defence submits that, by disclosing Ms. Manning's materials, Mr. Assange was acting within the parameters of responsible journalism. The difficulty with this argument is that it vests in Mr. Assange the right to make the decision to sacrifice the safety of these few individuals, knowing nothing of their circumstances or the dangers they faced, in the name of free speech. In the modern digital age, vast amounts of information can be indiscriminately disclosed to a global audience, almost instantly, by anyone with access to a computer and an internet connection. Unlike the traditional press, those who choose to use the internet to disclose sensitive information in this way are not bound by a professional code or ethical journalistic duty or practice. Those who post information on the internet have no obligation to act responsibly or to exercise judgment in their decisions. In the modern era, where "dumps" of vast amounts of data onto the internet can be carried out by almost anyone, it is difficult to see how a concept of "responsible journalism" can sensibly be applied.

Baraitser found that Assange would have been charged with similar crimes for his actions had they taken place in England or Wales, rejecting the defense claims that Assange's indictment was political in nature.

Nevertheless, the judge rejected the extradition request because of how America's federal prison system operates. She noted that Assange, given the nature of the charges, faces a high likelihood of "restrictive special administrative measures" that could potentially leave him in isolation, unable to communicate with the outside world, while the charges make their way through the court. Baraitser's ruling quotes at length several accounts of the cruel isolation and its impacts on those who are subjected to solitary confinement in prison, and Jeffrey Epstein's suicide last year is mentioned.

Assange has been diagnosed with depression, and according to the ruling, has claimed to be experiencing visual hallucinations and to be regularly thinking about suicide. Multiple doctors testified about his poor mental state. A psychiatrist who visited Assange testified that segregation or solitary confinement in prison could lead to further psychological decline. The judge determined "Mr. Assange's risk of committing suicide, if an extradition order were to be made, [would] be substantial."

And so for that reason, and only that reason, was the request to extradite Assange rejected. The United States is appealing the decision. In a statement, representatives from the Justice Department said it was "gratified that the United States prevailed on every point of law raised."

While Assange is protected (at the moment) from facing trial in the United States for publishing leaked information, there is absolutely nothing in Baraitser's ruling that suggests she thinks that Assange's behavior amounted to legitimate journalism. She accepted every single argument presented by the federal government that Assange's behavior was not protected speech.

The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University very quickly put out a statement after the ruling warning people that the Assange ruling was not, in fact, a win for the freedom of the press.

"The court makes clear that it would have granted the U.S. extradition request if not for concerns about Assange's mental health, and about the severe conditions in which the U.S. would likely imprison him," Jameel Jaffer said. "In other words, the court endorses the U.S. prosecution even as it rejects the U.S. extradition request. The result is that the U.S. indictment of Assange will continue to cast a dark shadow over investigative journalism. Of particular concern are the indictment's counts that focus on pure publication—the counts that charge Assange with having violated the Espionage Act merely by publishing classified secrets. Those counts are an unprecedented attack on press freedom, one calculated to deter journalists and publishers from exercising rights that the First Amendment should be understood to protect."

Show Comments (24)