Would the ACLU Still Defend Nazis' Right To March in Skokie?

Former Executive Director Ira Glasser discusses the past, present, and increasingly shaky future of free speech.

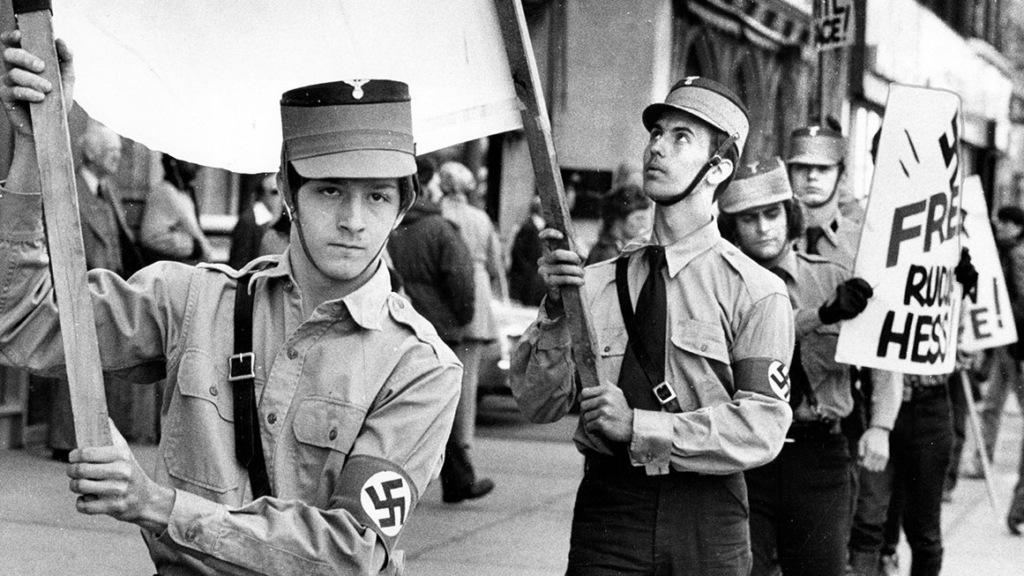

In 1977, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) went to court to defend the rights of American neo-Nazis to march through the streets of Skokie, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago home to many Holocaust survivors. The group defended the Nazis' right to demonstrate and won the case on First Amendment grounds, but 30,000 members quit the organization in protest.

The Skokie case cemented the image of the ACLU as a principled defender of free speech. The following year, Ira Glasser was elevated from head of the New York state chapter to the national organization's executive director, a position he would hold for the next 23 years. Now he's the subject of a new documentary, Mighty Ira, that celebrates his time leading the charge against government regulation of content on the internet, hate speech laws, speech codes on college campuses, and more.

Retired since 2001, Glasser says he's worried about the future of both free expression and the organizations that defend it. In 2018, a leaked ACLU memo offered guidelines for case selection that retreated from the group's decadeslong content-neutral stance, citing as a reason to decline a case "the extent to which the speech may assist in advancing the goals of white supremacists or others whose views are contrary to our values." Glasser fears that, by becoming more political and less absolutist when it comes to defending speech, the ACLU might be shrugging off its hard-won legacy.

In October, Glasser spoke with Reason's Nick Gillespie via Zoom.

Reason: The incident that dominates Mighty Ira is Nazis marching in Skokie, Illinois, in the late 1970s. Set the scene for that.

Glasser: What was going on in Skokie started in Chicago. This group of neo-Nazis, maybe 15 or 20 crazies, were against racial integration, not Jews. They were anti-Semitic, to be sure, but mostly against integration of schools and housing. Most lived on one side of Marquette Park in Chicago. On the other side was a predominantly black neighborhood. The Martin Luther King Jr. Association, a civil rights group in Chicago, used to demonstrate in the park in favor of integration, so it became a place where neo-Nazis and civil rights activists would frequently clash in contiguous demonstrations. I don't remember it breaking out into violence, but it was always tense and the city was always busy policing it. So the city threw up its hands, tired of spending time and energy navigating these two groups exercising their free speech rights, and passed a law saying nobody can demonstrate in Marquette Park unless they first post a $250,000 insurance bond against the possibility of damage to the park.

The problem with the bond is that no insurance company will sell it to you. These two small groups could not afford it. Insurance bond requirements like that had been frequently used against civil rights marches in the South and had always been struck down, usually [with the help of] the ACLU, as transparent attempts to stop speech that small towns in the South didn't like.

So as soon as we saw that the city of Chicago had done that, ACLU of Illinois lawyers' ears perked up. Sure enough, the Martin Luther King Jr. Association comes marching into our office one day and asks if we'll represent them in challenging it. It was an easy call, because we had always represented groups challenging bonding requirements. We filed a suit.

A few days later, Frank Collin of the neo-Nazi group asked us to do the same thing. The lawyers said they already had this case in the courts. His response was, "You don't have it for us." They said, "No, but it will apply to you. It's the same thing. It doesn't matter whether it was filed on your behalf or the Martin Luther King Jr. Association—it's the same challenge. When we win it—as we will—it will knock out the requirement for both of you. It can't be that the requirement will only apply to one and not the other." [Collin's group was] inconsolable and wanted to know how long it would take. I said, "We'll win, the city will appeal, we'll win there, the city will appeal again. It could go on for a while. It might be a year. It might be longer."

Neo-Nazis are very impatient and thin-skinned.

Well, they are, but anybody who wanted to demonstrate for something they believed in would be irritated by the fact that the city can pass a patently unconstitutional law, basically silencing you for a year and a half while lawyers strike down that law. There's something really outrageous about that, whether you're the neo-Nazis or the Martin Luther King Jr. Association or somebody demonstrating for or against abortion, or whatever.

So Collin decides: To hell with this. He'll go to the suburbs, where many of those who are governing Chicago actually live. He writes a letter on his neo-Nazi stationery to a dozen suburbs on Chicago's outskirts announcing that he's coming there to demonstrate against integration. All except one ignored his letter, because everybody knew who he was. The only suburb that responded was the town of Skokie. They responded, because the idea that neo-Nazis were going to come where a lot of Holocaust survivors lived was like a red flag to a bull, understandably.

This is only 30 or 35 years after World War II.

This is 1977. So it's still very fresh and there are survivors living there who went through unimaginable horrors. But they got the wrong advice. They should've ignored these people, because they had no capacity to go to all these suburbs. But when Skokie said, "You better not come here. We won't let you," [the neo-Nazis] had an opportunity for publicity of the kind that they could never get.

Skokie passed three new laws. One was a law banning anybody from marching in uniform. That was later used against the Jewish war veterans who wanted to have a parade. They passed a ban on speech that the town found offensive. If that law had ever been upheld, every town in the South could have banned civil rights marches, which they found offensive. And they passed an insurance bond requirement, just like Chicago. So that did it. [The neo-Nazis] said, "We're going to protest these laws in front of town hall."

City officials in Skokie advised the Holocaust survivors to ignore them and go inside their houses when they come. Pull the blinds down, just stay quiet. Just hide. Several of them had had that advice before, when they lived in Poland in 1939. This was an unbelievably painful history repeating itself. They knew that you don't hide from this; you demonstrate against it. This wasn't Germany, this was America. National Jewish groups like the Anti-Defamation League came in. The whole thing escalated.

Taking this case was never internally controversial. We did a dozen or two dozen of these kinds of cases every year.

The ACLU famously supported the rights of Ku Klux Klan groups to march throughout the South.

Sure, in Mississippi. None of us anticipated the storm that occurred, because we had taken cases like these forever. They were usually mildly controversial, but the law was perfectly clear. There was no way we were going to lose this case. If we did, we would lose it for the Martin Luther King Jr. Association at the same time, and for all of the other people we represented who were fighting for reproductive freedom, gay rights, disability rights.

So we continued to do the case we had from Chicago, because that case would have determined the law for the whole state, including Skokie. And we never would've represented the Nazis, because there was no need to. Then the town of Skokie got a court order barring the Nazis on the basis of these unconstitutional laws, which we were already challenging in Chicago. So it was only when Skokie went to court that we were then compelled to represent the Nazis, because we were already representing the Martin Luther King Jr. Association on the same issue. The two cases involved the same legal principle. It was Skokie's missteps that created that case.

What were the Nazis like?

I was head of the New York Civil Liberties Union, so I wasn't involved in those details, but I had been involved in similar cases. I had talked to David Goldberger, the ACLU lawyer in Illinois who did the case, and David Hamlin, then–executive director of the ACLU of Illinois. And yeah, you sit down with the client. Some conversations are more orderly than others. David Goldberger was a Jewish lawyer from Chicago, and here he was talking to these people who regarded him as vermin. And I'm sure he regarded them as vermin.

What the public sees is, "Oh, there's the ACLU representing the Nazis." We never see it that way. We were trying to oppose the government using the insurance bond requirement to prevent free speech. For us it didn't matter who the client was, because we would use that client to strike down the bond requirements, and that would apply to everybody.

Did the other groups that you were representing understand that?

Some did. Back in New York, there was a state law that required people who wanted to run for statewide office to get 10,000 names on a petition to gain ballot access. They also had to get at least 50 names from every county in New York. One day, the Socialist Workers Party came to us and said they're trying to run a candidate for governor. They've got 20,000 names, but they don't have 50 [from every county] and they don't have the money to travel. We had the same complaints from other minor parties. So we decided to strike this down and ended up planning a lawsuit on behalf of the Socialist Workers Party, the Socialist Labor Party, the American Communist Party, the [neo-fascist] National Renaissance Party.

We had to get them all to sign affidavits about why they needed this law struck down and how it interfered with their ballot access. We said, all right, let's do it on the weekend. So we came into the Civil Liberties Union office in New York with representatives from all of these groups. And the lawyer has all the affidavits, and they're each signing it.

This very interesting thing happened: One by one, almost every one of them comes up to me on the side, grabs me by the shoulder, and says, "Mr. Glasser, I wanted to thank you for this. This is a great thing that you're doing to help us get on the ballot. But let me ask: Why do we have to have all these other people?" Because their position was, this was their right. Our position was this was everybody's right or nobody's right.

I used to joke that when people would say the trouble with free speech in America is that so few people support it, my response was always, "No, you're wrong. Everybody in America supports free speech so long as it's theirs or people they agree with." Even in our own membership, the perception was that the ACLU was representing Nazis, not that the ACLU was opposing a government restriction on your speech.

How did Skokie turn out?

We won the case at every level. It even went up to the Supreme Court. It was an easy case legally because these bonding statutes had been struck down a million times before.

Meanwhile, some of the people who lived in Skokie—once we won the case and the Nazis said they were coming—did what the town should've advised them to do in the first place: They organized a massive counter-demonstration. About 60,000 people were ready to come. And then the irony of ironies is, when confronted with that, Collin and the neo-Nazis never came to Skokie. Once we won that case, it also allowed them to demonstrate in Marquette Park, which was what they had wanted to do all along. They also confronted a massive counter-demonstration there that never would have happened without the case. It completely overwhelmed them; they couldn't be seen or heard. Right after that they fell apart.

You were born in 1938 in Brooklyn. You started out as a mathematician, and you got drawn into politics by the civil rights movement. What about civil rights activated you?

The most major thing was race. Racial oppression was a big deal, because you could see that everywhere. As a Dodgers fan, I was 9 years old when [Jackie] Robinson broke in, and I learned a lot about racial exclusion and subjugation. The first place I learned about Jim Crow laws was when the Dodgers went to St. Louis. That's how I found out Robinson, [Roy] Campanella, and [Don] Newcombe couldn't stay with the team in the same hotel and couldn't eat in the same restaurants. I didn't learn that in school. I learned that from [sports announcer] Red Barber, with his Mississippi drawl, broadcasting Dodgers games. That was how I came to hate it, because Robinson was my guy. When I got to the ACLU in 1967, I was 29 years old. Dealing with remedies for racial subjugation was my passion.

It wasn't until my 30s that I began to understand free speech, that the real antagonist of speech is power. The only important question about a speech restriction is not who is being restricted but who gets to decide who is being restricted—if it's going to be decided by Joe McCarthy, Richard Nixon, Rudy Giuliani, [President Donald] Trump, or [Attorney General] William Barr, most social justice advocates are going to be on the short end of that decision. I used to say to black students in the '90s who wanted to have speech codes on college campuses that if [such codes] had been in effect in the '60s, Malcolm X or Eldridge Cleaver would have been their most frequent victim, not David Duke.

Was that a convincing argument?

It pulled people up short. They imagined themselves as controlling who the codes would be used against. I would tell them that speech restrictions are like poison gas. It seems like it's a great weapon to have when you've got the poison gas in your hands and a target in sight, but the wind has a way of shifting—especially politically—and suddenly that poison gas is being blown back on you.

Mighty Ira makes a big deal out of your relationship with William F. Buckley—the conservative co-founder of National Review who was at various points in favor of censorship—to make a point about civility and disagreement. Is civility overrated?

To a point. I've seen vigorous advocacy demonized and suppressed on the grounds that it wasn't civil. I once had somebody at the ACLU propose a new policy for us that would oppose speech that demeaned and insulted people. I got up at that conference and said, "Well, every time I open my mouth, I'm looking to demean or insult somebody because of their views, and I'm about to do it again." I proceeded to attack that, because in the hands of malevolent power, a statute like that would suppress speech in the name of civility.

On the other hand, my relationship with Buckley is a little bit misunderstood. I was brutal to him in those debates. In one, I dug out a column he had written for National Review in the '50s opposing the Civil Rights Act and confronted him on the air.

The first time I had dinner at his home, his wife Pat came up to me sort of half tongue-in-cheek and said, "Oh, I'm so glad to meet you. But how come you're so nasty to my husband on television?" I looked at her and said, "Pat, he says so many terrible things." So the civility was of that kind—in private, we could deal with each other and our disagreements in a civilized way, but it didn't diminish the vigor of our arguments or our denunciations of the other's position when we were debating in public.

I used to joke with him and say, "I think actually you're a better friend to me than I am to you, because I'm always just a little leery when we're together." He was a very kind person in private. I had dinner at his house once, and he had a cook who was not comfortable speaking English. He was fluent in Spanish—I think it was his first language, actually—and he spoke to her in Spanish and was very kind and solicitous. I found him to be that way pretty consistently, but that didn't change the regressiveness of his positions or the vigor with which I was prepared to attack them. So there's a bit of a difference between private and public. That line may be a little erased these days.

A lot of politicians, despite their public commitments, are not particularly interested in free speech. Can you talk about the 1997 case Reno v. ACLU, where you challenged speech restrictions in the Communications Decency Act?

It was decided by the Supreme Court—a decisive victory. The internet at that time was a relatively new platform for speech. Anytime there's a new platform that democratizes speech, the government gets nervous. In the 15th century, when the printing press was invented, the reaction of the English government and the Church was hysterical. England passed a law requiring anybody who owned a printing press to register it with the government as if it were a dangerous weapon. The law limited the number of printing presses that could exist and required that before you could publish a book with one of these newfangled printing presses, you had to get a government license. You had to give them the book to read, and then they would decide whether you could publish it. They also did searches of people's homes to find out whether they had any books or newspapers that violated those laws—the model for the illegal searches that happened in the colonies in the 18th century.

The government and the Church responded to the democratization of speech with a ferocity of censorship that went on for hundreds of years. By the time the First Amendment was passed in America in 1791, you're talking more than 300 years since the printing press was first invented.

When the internet was invented, it suddenly widened the number of people who had the capacity to speak, and it widened by even more the number of people who could hear what they said. The government reacted the same way: They developed schemes to censor, license, and restrict it, and that's what the Communications Decency Act was. Violations were punishable by up to two years in prison and a quarter-million-dollar fine. How many people on the internet could afford that for saying anything on the internet that was offensive or indecent? Now, of course, nobody knows what that means; it means something different to everybody. But all I'm thinking at the time is, "This is England all over again, and I don't want [enforcement by] Rudy Giuliani, against whom we had to file 27 lawsuits for violations of the First Amendment for trying to censor paintings in the Brooklyn Museum. I don't want people like [former Sen.] Joe McCarthy deciding what's offensive."

Can I just stress that it was then–Attorney General Janet Reno and Democratic President Bill Clinton—

All that proves is that free speech opponents do not organize themselves according to party. It has been true in my lifetime that conservatives have more often been against free speech. Liberals and progressives have, in my lifetime, more often been for it. But in the early '60s, the New York Civil Liberties Union represented Buckley against the [head] of Hunter College; Buckley was signed up to debate or speak, and [President John J.] Meng had banned him. The New York Civil Liberties Union, before I was there, represented him. In the very first free speech political case I became aware of, the organization represented not a neo-Nazi but a respected conservative against a liberal in a dominantly liberal university.

Next to slavery and the homicidal, genocidal destruction of American Indians, the worst civil liberties violation that occurred in this country en masse was the incarceration of Japanese-American citizens during World War II. You know which president signed that executive order? Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was a god in my parents' house because he had saved them from ruin financially. But for me, the antagonist of civil liberties and free speech is not this or that party; it's power, whoever holds it.

In 2018, a leaked ACLU memo came out where the group seemed to be walking away from the idea of viewpoint neutrality when it came to protecting speech. The ACLU now advises its affiliates to consider the content of speech and whether it advances the group's goals before deciding whether to defend the right to speak. How do you feel about that?

I'm 20 years gone from steering this ship. I don't really know a lot more about what's going on than you do. That memo did in fact introduce a content-based consideration to whether they would take a free speech case, enough so that it made me wonder, "If Skokie happened again, would the ACLU take it?" It's not politically outrageous during times like these for the ACLU to want to become more of a political organization than a civil liberties organization. That's not surprising, and there's nothing evil about it. An organization has a perfect right to change its agenda or mission, to say, "The times require us to be something different than what we were." The ACLU has taken a few steps toward doing that, I think, but they've denied it.

There are a lot of progressive political groups out there. I'm glad to have more of them, because that's my politics too. But there's only one ACLU. It doesn't matter on whose behalf the immediate client is. What matters is you have to stop the government from gaining the power to decide. It's taken 100 years for the ACLU to develop from the 30 or 40 people that started it in 1920 to the powerhouse of civil liberties that it is today. If the ACLU isn't there for speech, who will be?

I grew up in an era where your broad view of the value of free speech was culturally dominant. What has happened to change that?

I went to one of the half-dozen best law schools in the country a year or two ago to speak. And it was a gratifying sight to me, because the audience was a rainbow. There were as many women as men. There were people of every skin color and every ethnicity. It was the kind of thing that when I was at the ACLU 20, 30, 40 years ago was impossible. It was the kind of thing we dreamed about. It was the kind of thing we fought for. So I'm looking at this audience and I am feeling wonderful about it. And then after the panel discussion, person after person got up, including some of the younger professors, to assert that their goals of social justice for blacks, for women, for minorities of all kinds were incompatible with free speech and that free speech was an antagonist.

As I said, when I came to the ACLU, my major passion was social justice, particularly racial justice. But my experience was that free speech wasn't an antagonist. It was an ally. It was a critical ally. I said this to the audience, and I was astonished to learn that most of them were astonished to hear it—I mean, these were very educated, bright young people, and they didn't seem to know this history—I told them that there is no social justice movement in America that has ever not needed the First Amendment to initiate its movement for justice, to sustain its movement for justice, to help its movement survive.

Martin Luther King Jr. knew it. Margaret Sanger knew it. [The labor leader] Joe Hill knew it. I can think of no better explication of it than the late, sainted John Lewis, who said that without free speech and the right to dissent, the civil rights movement would have been a bird without wings. And that's historically and politically true without exception. For people who today claim to be passionate about social justice to establish free speech as an enemy is suicidal.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity. For a podcast version, subscribe to The Reason Interview With Nick Gillespie.

Show Comments (248)