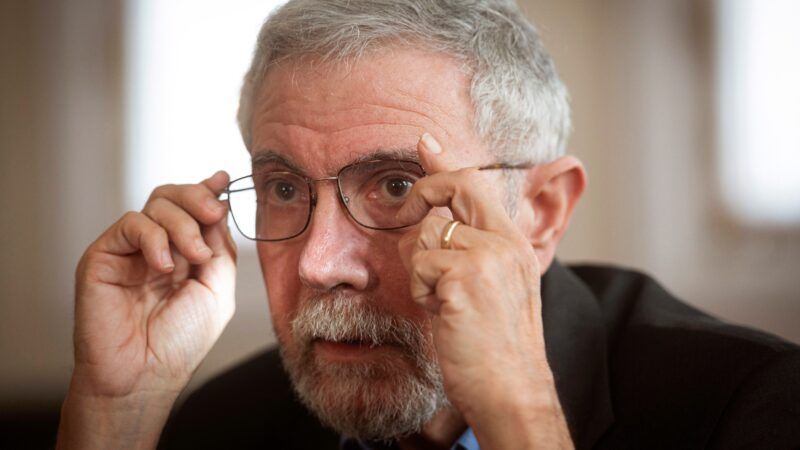

Paul Krugman Thinks Holding Religious Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic Is Like 'Dumping Neurotoxins Into Public Reservoirs'

The New York Times columnist misconstrues the issues at stake in the challenge to New York's restrictions on houses of worship.

When the Supreme Court blocked New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo's restrictions on religious services this week, it was the first time the justices had enforced constitutional limits on government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The decision predictably provoked hyperbolic reactions from critics who seem to think politicians should be free to do whatever they consider appropriate during a public health crisis.

Describing the Court's emergency injunction in Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo as "the first major decision from the Trump-packed court," New York Times columnist Paul Krugman warned that "it will kill people." He added: "The bad logic is obvious. Suppose I adhere to a religion whose rituals include dumping neurotoxins into public reservoirs. Does the principle of religious freedom give me the right to do that?" Krugman averred that "freedom of belief" does not include "the right to hurt other people in tangible ways—which large gatherings in a pandemic definitely do."

There are several problems with Krugman's gloss on the case, starting with his understanding of the constitutional right at stake. The Court was applying the First Amendment's ban on laws "prohibiting the free exercise" of religion, which includes conduct as well as belief. Krugman, of course, is right that the Free Exercise Clause is not a license for "dumping neurotoxins into public reservoirs"—or, to take a more familiar example, conducting human sacrifices. But it is hard to take seriously his suggestion that holding a religious service during the COVID-19 pandemic, regardless of the safeguards observed, is tantamount to poisoning millions of people's drinking water.

Under Cuomo's rules, "houses of worship" in state-designated "red" zones were not allowed to admit more than 10 people; the cap in "orange" zones was 25. Those restrictions applied regardless of a building's capacity. A 1,000-seat church, for example, would be limited to 1 percent of its capacity in a red zone and 2.5 percent of its capacity in an orange zone.

Cuomo's restrictions on religious gatherings were much more onerous than the rules for myriad secular activities that pose similar risks of virus transmission. That point was crucial because the Court has held that laws are presumptively unconstitutional when they discriminate against religion. At the same time, it has said the Free Exercise Clause does not require religious exemptions from neutral, generally applicable laws, which obviously would include statutes that prohibit mass poisoning or murder.

It is undisputed that both the Brooklyn diocese and Agudath Israel, which sued Cuomo on behalf of the Orthodox synagogues it represents, were following strict COVID-19 safety protocols, including face masks and physical distancing. It is also undisputed that no disease clusters have been tied to their institutions since they reopened. The plaintiffs were not asking to carry on as if COVID-19 did not exist. They were instead arguing that Cuomo's policy singled out houses of worship for especially harsh treatment and was not "narrowly tailored" to serve the "compelling state interest" of curtailing the epidemic.

After these organizations filed their lawsuits but before the Supreme Court considered their request for an emergency injunction, Cuomo changed the color coding of the neighborhoods where their churches and synagogues are located. "None of the houses of worship identified in the applications is now subject to any fixed numerical restrictions," Chief Justice John Roberts noted in his dissenting opinion. "At these locations, the applicants can hold services with up to 50% of capacity, which is at least as favorable as the relief they currently seek."

In other words, Cuomo suddenly increased the effective occupancy cap for a 1,000- seat church 50-fold in formerly red zones and 20-fold in formerly orange zones. By Krugman's logic, the governor is now allowing behavior as reckless as "dumping neurotoxins into public reservoirs." Yet this is the same man whose judgment on these matters Krugman thinks we should trust without question.

"The scary thing is that 5 members of the court appear to think they're living in the Fox cinematic universe, where actual facts about things like disease transmission don't matter," Krugman says. If so, Cuomo himself seems to have succumbed to the same propaganda, since he concluded that his original rules were far more restrictive than necessary.

New York Times reporter Adam Liptak suggests that the 5-to-4 decision in this case, which hinged on the replacement of Ruth Bader Ginsburg with the recently confirmed Amy Coney Barrett, reflects a new conservative majority driven by political considerations. "Chief Justice Roberts is fundamentally conservative, and his liberal votes have been rare," Liptak writes. "But they reinforced his frequent statements that the court is not a political body. The court's new and solid conservative majority may send a different message."

Yet the six opinions issued on Wednesday night, no matter their conclusions, do not simply express policy preferences or partisan allegiances. They show the justices grappling with constitutional issues, as they are supposed to do.

Was Cuomo's policy neutral and generally applicable? The five justices in the majority did not think so. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan disagreed, arguing that houses of worship are not fundamentally similar to the many businesses that Cuomo allowed to operate without occupancy limits. Roberts, while arguing that an injunction was unnecessary in light of Cuomo's sudden reclassification of the relevant neighborhoods, nevertheless conceded that "numerical capacity limits of 10 and 25 people, depending on the applicable zone, do seem unduly restrictive," and "it may well be that such restrictions violate the Free Exercise Clause."

Justice Stephen Breyer split the difference. "Whether, in present circumstances, those low numbers violate the Constitution's Free Exercise Clause is far from clear," he wrote, "and, in my view, the applicants must make such a showing here to show that they are entitled to 'the extraordinary remedy of injunction.'"

In other words, while only five justices agreed that an emergency injunction was appropriate, seven were prepared to at least entertain the possibility that Cuomo's restrictions were unconstitutional. Perhaps that proposition is not as outlandish as critics like Krugman think.

Leaving aside the specific legal issues raised by this case, the broader question is whether a public health emergency makes constitutional constraints optional. COVID-19 lockdowns that blocked access to abortion by classifying it as a nonessential medical service, for example, have been successfully challenged in several states. Does Krugman think those courts should have shown the same deference to politicians he believes is appropriate when restrictions on religious freedom are challenged?

In a Harvard Law Review Forum essay published last July, American University law professor Lindsay Wiley and University of Texas at Austin law professor Stephen Vladeck present a forceful argument against suspending the usual standards of judicial review during a crisis like the COVID-19 epidemic. They note that "the suspension principle is inextricably linked with the idea that a crisis is of finite—and brief—duration"; it is therefore "ill-suited for long-term and open-ended emergencies like the one in which we currently find ourselves." They add that "the suspension model is based upon the oft-unsubstantiated assertion that 'ordinary' judicial review will be too harsh on government actions in a crisis"—a notion that seems misguided given that "the principles of proportionality and balancing driving most modern constitutional standards permit greater incursions into civil liberties in times of greater communal need."

Wiley and Vladeck emphasize "the importance of an independent judiciary in a crisis—'as perhaps the only institution that is in any structural position to push back against potential overreaching by the local, state, or federal political branches.'" They quote George Mason law professor (and Volokh Conspiracy blogger) Ilya Somin's observation that "imposing normal judicial review on emergency measures can help reduce the risk that the emergency will be used as a pretext to undermine constitutional rights and weaken constraints on government power even in ways that are not really necessary to address the crisis." Without such review, Wiley and Vladeck warn, "we risk ending up with decisions like Korematsu v. United States," the notorious 1944 ruling that upheld the detention of Japanese Americans during World War II. The risk of excessive deference, they note, is that courts will "sustain gross violations of civil rights because they are either unwilling or unable to meaningfully look behind the government's purported claims of exigency."

Justice Neil Gorsuch's concurring opinion in Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo amplifies that point. "Even if the Constitution has taken a holiday during this pandemic, it cannot become a sabbatical," he writes. "We may not shelter in place when the Constitution is under attack. Things never go well when we do."

Show Comments (264)