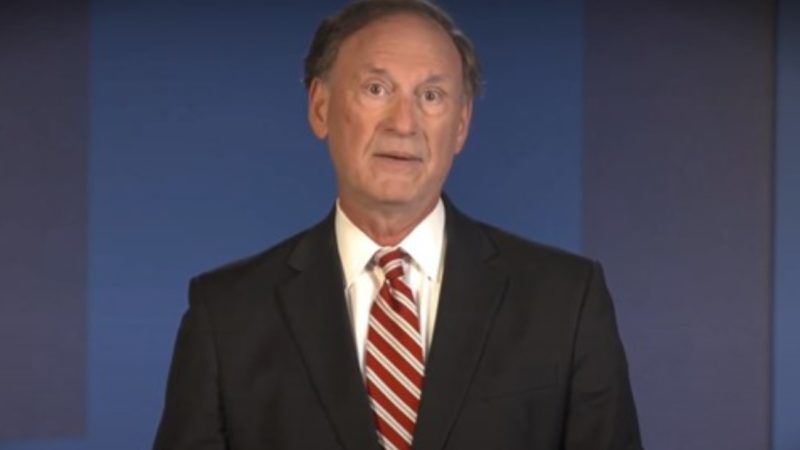

Justice Samuel Alito Highlights the Legal Issues Raised by 'Previously Unimaginable' COVID-19 Restrictions

When "fundamental rights are restricted" during an emergency, he says, the courts "cannot close their eyes."

During a Federalist Society speech last night, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito called attention to the legal issues raised by the sweeping social and economic restrictions that all but a few states imposed this year in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. "The pandemic has resulted in previously unimaginable restrictions on individual liberty," Alito noted in his remarks, which he delivered via Zoom. "We have never before seen restrictions as severe, extensive, and prolonged as those experienced for most of 2020."

One of the issues raised by those restrictions is the extent of executive authority in dealing with emergencies. The COVID-19 lockdown imposed by Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak, for example, was based on a statute that gave him the authority, in the event of "a natural, technological or man-made emergency or disaster of major proportions," to "perform and exercise such…functions, powers and duties as are necessary to promote and secure the safety and protection of the civilian population." As Alito noted, "to say that this provision confers broad discretion would be an understatement."

While "I'm not disputing that broad wording may be appropriate in statutes designed to address a wide range of emergencies," Alito said, "laws giving an official so much discretion can, of course, be abused. And whatever one may think about the COVID restrictions, we surely don't want them to become a recurring feature after the pandemic has passed. All sorts of things can be called an emergency or disaster of major proportions. Simply slapping on that label cannot provide the ground for abrogating our most fundamental rights. And whenever fundamental rights are restricted, the Supreme Court and other courts cannot close their eyes."

In Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the 1905 ruling that was widely cited as a justification for COVID-19 lockdowns, the Supreme Court rejected a challenge to mandatory smallpox vaccination. But that situation was quite different from edicts ordering all "nonessential" businesses to close and commanding hundreds of millions of Americans to remain in their homes except for government-approved purposes. Jacobson's "primary holding," Alito noted, "rejected a substantive due process challenge to a local measure that targeted a problem of limited scope. It did not involve sweeping restrictions imposed across the country for an extended period. And it does not mean that whenever there is an emergency, executive officials have unlimited, unreviewable discretion."

To the contrary, the Court in Jacobson noted that the public health powers exercised by state and local governments, while broad, are not unlimited. Those powers "may be exerted in such circumstances, or by regulations so arbitrary and oppressive in particular cases, as to justify the interference of the courts to prevent wrong and oppression," Justice John Marshall Harlan noted. "An acknowledged power of a local community to protect itself against an epidemic threatening the safety of all might be exercised in particular circumstances and in reference to particular persons in such an arbitrary, unreasonable manner, or might go so far beyond what was reasonably required for the safety of the public, as to authorize or compel the courts to interfere for the protection of such persons."

The question confronting courts right now is when disease control measures exceed those bounds. While Alito did not venture a general answer, he cited as an example a case the Supreme Court already has considered, involving Nevada's restrictions on religious services. Under Gov. Sisolak's reopening plan, the rules for houses of worship were stricter than the rules for other venues—including casinos, bars, restaurants, gyms, arcades, and bowling alleys—where the risk of virus transmission was at least as high. The Court nevertheless declined to hear a First Amendment challenge arguing that the state was engaging in unconstitutional discrimination against religious activities.

Alito, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh, dissented from that decision, and last night he recapitulated his take on the case. "If you go to Nevada," he said, "you can gamble, drink, and attend all sorts of shows. But here's what you can't do: If you want to worship and you're the 51st person in line, sorry, you are out of luck. Houses of worship are limited to 50 attendees. The size of the building doesn't matter. Nor does it matter if you wear a mask and keep more than six feet away from everybody else. And it doesn't matter if the building is carefully sanitized before and after a service. The state's message is: Forget about worship and head for the slot machines, or maybe a Cirque du Soleil show."

In Alito's view, "deciding whether to allow this disparate treatment should not have been a very tough call." In the Constitution, he said, "you will see the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment, which protects religious liberty," but "you will not find a craps clause or a blackjack clause or a slot machine clause. Nevada was unable to provide any plausible justification for treating casinos more favorably than houses of worship. But the Court nevertheless deferred to the governor's judgment, which just so happened to favor the state's biggest industry and the many voters it employs."

Alito contrasted the outcome of that case with the pandemic-inspired injunction that a federal judge in Maryland issued in July against enforcement of the Food and Drug Administration's requirement that women visit a health care provider before obtaining the abortion drug mifepristone, a.k.a. RU-486. In light of the COVID-19 risks it entailed, U.S. District Judge Theodore D. Chuang concluded, that requirement imposed an "undue burden" on the constitutional right to abortion.

Last month, the Supreme Court declined to issue a stay against that injunction, saying "a more comprehensive record would aid this Court's review." Alito, joined by Thomas, dissented. "If deference was appropriate" in the Nevada case, Alito said last night, "then surely we should have deferred to the federal Food and Drug Administration on an issue of drug safety." But because the case involved abortion rights rather than religious liberty, he suggested, the plaintiffs were more successful.

Leaving aside Alito's perspective on Roe v. Wade, he is no doubt right that progressives tend to view abortion restrictions, even when they are imposed in the name of fighting COVID-19, with more skepticism than they apply to limits on church services. Lockdowns that classified abortion as a nonessential medical service have been successfully challenged in several states. For the many Americans who supported those challenges, preventing women from obtaining abortions was a clear example of what Justice Harlan was talking about in Jacobson: disease control measures that are "arbitrary," "unreasonable," and go "far beyond what [is] reasonably required for the safety of the public," requiring courts "to interfere for the protection of such persons."

Slate's Mark Joseph Stern, who described Alito's speech as "ultrapartisan," cited the justice's discussion of COVID-19 restrictions to illustrate that point. But the constitutionality of specific disease control measures is not, or at least should not be, a partisan issue. It is something that should concern any American who values the freedoms protected by the Constitution and is wary of well-intentioned policies that override them in the name of the greater good.

While "I am not diminishing the severity of the virus's threat to public health," Alito said, it's clear that "the COVID crisis has highlighted constitutional fault lines." He warned that "there is only so much that the judiciary can do to preserve our Constitution and the liberty it was adopted to protect." He closed by paraphrasing Judge Learned Hand: "Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women. When it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can do much to help it."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Abortion is their religion.

Green Teeth? Izzat you bullying girls from behind that fake name sockpuppet?

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29658 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. I have joined this action 2 moniths back and I have earned $31547 in my first month from this action.AQw I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it

what I do............Click here

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29658 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. I have joined this action 2 months back and I have earned $31547 in my first month from this action. I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it

what I do.........work92/7 online

True. An old religion too, Leviticus 18 & 20, the depraved worship of the evil false god Molech of depraved Dems/media instead of the gracious true God on whom America was founded. It was so monstrously corrupt that they played loud music as they put their babies on heated metal idols so they wouldn't hear the screams. We're no better today, vainly pretending to be civilized with our saline et al abortions avoiding videos of the unborn like "The Silent Scream" lest we're awakened to the vile evil of what we're really doing. This is one of the many evils the depraved Biden corpse wants and Trump opposes.

I am now making more than 350 dollars per day by working online from home without investing(yes) any money.Join this link posting job now and start earning without investing or selling anything.

Follow Instructions Here....... Home Profit System

There needs to be a hague for the lizard people who pushed these policies.

There needs to be a reeducation camp for people who think emergency public health measures during a global pandemic are oppressive.

Cool tony, will you be doing the rounding up hero?

I wouldn't get near a Trump supporter even if they weren't all being bug chasers.

I look forward to the escalation of the new civil war you and your good friends started earlier this year. Now accounts can be settled and...... induhviduals....... such as yourself may be dealt with.

You are the whiniest motherfuckers this side of a 3 year old.

"You are the whiniest motherfuckers this side of a 3 year old."

Coming from the whiny 3 year old.

No Tony, I don’t whine. I leave that to you. And you are one huge bitch. Whiney, sloppy bottom, submissive weakling.

No wonder you’re such a bitch.

Seriously, I imagine you as a bitchier version of Colin Skittles.

Then why are you crying so much more than I did about losing an election?

Please you've been crying for four years. Gaslighting again Tony.

Only because of all the dead people and loss of national dignity.

you didn't cry for the 200,000+ dead syrians your heros helped kill

Man, Tony is getting their butt kicked. Oops, that was two days ago. Nevermind.

Per the standard methodology used for every other disease, the US has had fewer than 10,000 deaths from the Covids. Which is about what we expect from a cold. And the Covids are a cold.

Using the special, Covids-only metrics, it's killed about 25% of what the measles killed every year before the vaccine. Which is still not a significantly relevant number.

As the US has the 3rd highest population, we would reasonably expect it to have the third highest number of cases. China's numbers are never honest, and India lacks the infrastructure to count them. However, the US case count is stastically similar to all other Western nations, which is apparent to anyone capable of doing basic arithmetic (who identify themselves by not putting a D next to their name).

Only pussies and faggots are shitting their pants over a cold.

I kind of hope you get it and suffer. You're spreading stupid lies that were debunked months ago. Stop lying.

I haven’t cried one bit. Why would I. The election is in no way decided. Clearly, you’re confused.

Not surprising, as swishbucklers go, you are both weak and stupid.

Beyond parody.

Get a load of Chairman Tony over here. Don’t think that just because you’re a card-carrying party member, you’ll be immune from that midnight knock at your door.

Whether justified and legal or not, they are absolutely oppressive.

Dying slowly and painfully ain't no picnic either.

I’m glad you’re aware of that. Maybe you can somehow psychologically prepare for that inevitable end to your existence.

Or just do something smart and correct for once. Go drink Drano.

"Dying slowly and painfully ain’t no picnic either."

We hope you'll do so, shitstain.

President-Elect-in-Waiting AOC is drawing up plans already.

There needs to be a reeducation camp for people who think emergency public health measures during a global pandemic are effective.

FTFY.

Hey, Tony, if you're that afraid of a cold, just lock yourself in your house, seal all the windows with tape, wrap your head with 6 layers of plastic, and drink a bottle of Drano. I guarantee you won't die of The Covids.

The rest of us, who aren't pussy little faggots, can get on with our lives.

Interestingly, I've refused to comply with every single mandate in every state I've been in this year, and literally nothing has happened. Not a sniffle, not a sneeze, not a friend with either.

Almost as if a coronavirus is just a cold. Oh, wait, that's what Wikipee says.

Tony would've liked Salt Lake City during the 1918 Spanish Flu, when folks were urged to snitch on the maskless if not punch them out. Then again, before that a war protester was killed by a mob, and everyone acquitted after sth like 15 minutes' deliberation.

So, have you always been such a whiny, totalitarian, nutless, and fundamentally harmless bitchboi, or did it take years of practice?

Let us love you until you love yourself Tony

Fuck off, slaver.

Only gullible, stupid, mentally incompetent useful idiocy pretends the proven massive fraud of corrupt, lawless, fascist, blue state and RINO dictators we're experiencing is regarding a real global pandemic instead of the corrupt fascist religious exploitation it really is, ably exposed by https://hailtoyou.wordpress.com/2020/04/05/against-corona-panic/

The fraud is very like the attempt these corrupt, lawless, fascists to steal the election Trump won that is mathematically IMPOSSIBLE for the Biden corpse to have won. As with those who say the virus is a real threat, those who say Biden won are clearly and manifestly delusional, belonging in an asylum.

Emergency executive orders should not be permitted to extend beyond 14 days, during which they should be confirmed exactly as issued, or held void. Any order held void should not be re-issued in whole or in part.

Emergency means emergency; something that requires action before a legislative solution can be achieved.

Oh, yes, and every kid should have a pony.

sweet! pony tax!

>>Emergency executive orders should not be permitted to extend beyond 14 days

word.

pony privilege tax.

Every kid should have a pony? Not if Elaine Benes has something to say about it.

I. Had a pony!

We just need to find a power to enforce that limit on the executive. A higher executive?

And after those kids all get ponies, we ourselves will need to all get street cleaners, unless we can teach all those kids real fast.

This is actually a very good point.

The purpose of legislation that provides significant additional authority to the executive during an emergency is to allow things to happen faster than a legislature can act.

Unless the emergent condition is *so utterly severe* that the legislature cannot possibly convene, even virtually (giant meteor stroke, Yellowstone eruption, zombie apocalypse), after a point, it can no longer truly be considered emergent any longer.

Though Mr. Anthony below also makes a good point, who will enforce the limitation?

In about ten more weeks or so we’ll finally start to get a definitive answer as to what the left really cared about the most: getting Trump out of office or trying to make Agenda 21 totalitarianism in America permanent.

If it turns out to be the latter, they risk pushing America to our most dangerous place since the Civil War.

Agenda 21, lol. I bet you complain at your local QAnon meetings about how the conspiracies were much better when you were younger.

Or Agenda 2030 or the “Great Reset” or whatever fuckin’ term is now in vogue for it among you scumbags.

Ooooo. Scary tough guy masked sockpuppet. What did Mark Twain say about masks?

tWo WeEkS tO fLaTtEn ThE cUrVe

This was a disaster. Someone explain the logic here. The court gave gay people equal rights to marriage, and thus it became a first amendment problem for people to express opposition? Is there a law against expressing opposition to gay people? News to me.

A justice of the United States supreme court can't tell the difference between social pressure not to be a bigot and an infringement on his legal rights.

I am 100% in favor of him attending all the covid parties he wants.

Way to boil down the words into a pablum you could understand. Of course you managed to get it wrong as usual. Maybe you could get your legal advice from Kirkland.

The First Amendment includes religion as well as speech.

And don't forget assembly, and petitioning for redress of grievances, even outside Festivus.

And how are Justice Alito's first amendment rights being thwarted?

I applaud your conviction of being the dumbest but most persistent poster here. That's quite a low bar but you've met it. Just accept the persistence award.

I mean what 1st amendment right are being violated. All of them you fucking dipshit

Lets see we can't worship, but we can go to Walmart. we can't hang put at he pub but we can protest in the streets as long as its he right kind of protest.

God doesn't actually live in the church, you know.

Fuck off asshole.

No, no, it's "Fuck off, slaver". Although he *is* an asshole.

If morons like you didn’t feel a need to license every goddamned thing, then there would be no license for marriage, and you would have nothing to bitch about.

I don't believe that you gave a shit about marriage licenses until the gays wanted them.

I always thought they were stupid. I also think that two men together isn’t marriage. I would just prefer that the government not be involved so then I’m not involved.

Not that it matters to you. You’re so much of a narcissistic twat that you could never value another person enough to be a serious partner in a healthy relationship. You’re the epitome of a progressive democrat, self absorbed and obsessed with inflicting your idiotic feelings and ideas on everyone else.

I actually can't argue with about half of that.

More like 99.9% of it.

I’m opposed t gay marriage. I am far more opposed to government licensing any marriages.

Tony, if I were deciding how things worked, y would have far more personal freedom than you do now. However, you would be forced to leave everyone else’s lives the Hell alone.

https://twitter.com/Paramythia__/status/1326487012526841857?s=19

Kirawee High School NSW questionnaire for year 8 students.

These people shouldn’t be anywhere near children.

Thank god that is down under in Australia. These people are insane.

"Slate's Mark Joseph Stern..." Slate has been a self-parody from some years now.

I'm quite proud that I was banned from their site some years ago.

Justice Alioto is free to claim that the Supreme Court's decision in the Nevada case was "wrong", but people like me are also free to claim that the 2nd Amendment decisions finding a right to self-defense enshrined in the Constitution were "wrong" as well (see Justice Stevens' dissent in those cases for more detail).

I look forward to you putting that into practice, corpse.

Stevens defense of Kelo v New London still pisses me off all this time later. His opinion on the right to self-defense was even more tone deaf and illogical. Anyway the courts have upheld firearms ownership and nothing is going to change that.

What did you just say? So did you read 1A and 2A.? What part don't understand?

If you disagree with what they say start an amendment

"...but people like me are also free to claim that the 2nd Amendment decisions finding a right to self-defense enshrined in the Constitution were “wrong” as well..."

You misspelled "lefty shits", lefty shit.

Stevens’ dissent is a steaming pile of illogical bullshit.

If you insist that logical consistency and sensible application of reason is inferior to arriving at the conclusion that you already decided that you wanted is "wrong" sure.

Alito was talking about the Patriot Act and the drug war, right?

He was indeed talking about a law relating to drugs.

Why would a libertarian blog not mention Justice Alito's bigoted advocacy of statist gay-bashing (which consisted mainly of whining about how modern people call a bigot a bigot)?

There is no scientific support for lockdowns. Cogent arguments why they fail to accomplish their goals were made as long ago as 2007. So even if one disregards the moral and legal hazards lockdowns impose on liberty and economies, there is no scientific rationale for them.

Forgot to mention that as far as I can determine, lockdowns were only proposed circa 2006, hence there was no need to argue against them much prior to that time frame.

AIER....read the essays there. Jeffrey Tucker lays it all out; revealing that it wasn't contrived by scientists, but instead, modelers.

Regardless, there should have been rioting in the streets in February and March.

Lockdowns are a great litmus test for how much the people are willing to tolerate from government, however. That’s what this COVID saga is transforming into; a social test of the people’s tolerance of lost income, lost recreational activities, and loss of “non-essential” services. As well as a measure of the people’s trust in science based claims from authority (e.g. “Get rid of your N95 mask, and use these cloth ones”).

This obviously wasn’t the original intent of the lockdowns, but there’s value in knowing what people will tolerate. Especially to the “Fundamental Transformation” crowd currently making gains in government.

Is this something that a state or municipal government isn't allowed to do? Is the federal government supposed to prevent them from making their own pandemic response policy?

You read my comment even less closely than I read the article.

Well he's a dumbshit, so??

HAHAHAHAHAHA

"...Is the federal government supposed to prevent them from making their own pandemic response policy?"

If those policies violate the constitution, yes, the DOJ has a duty to step in.

I'm sure that's a surprise to you; you might read something about Littlerock in 1957 as I'm sure you never heard of it.

And we as Americans have failed that test miserably.

Not as badly as the Euros who are now in full lockdown again.

Not as badly YET.

The first test might've been Boston Strong, which I always hear in an eastern European and/or caricature American Indian accent.

You just don’t do it. Right? Civil disobedience? No need to break stuff or smash it. We just refused the lockdown thing. That’s what we’re been doing since March (live in CA)

Probably spreading COVID all over the place though... :O

Justice Alito has sounded the alarm. Hopefully, many are listening. Our individual civil liberties are being eroded, and it has to stop. Sooner or later, the government will expand it's power in the next 'emergency'.

When the hillside starts to wash away, that's erosion.

Once the road is wiped out, it's gone.

Alito makes good points but what about the likely thousands of innocent Americans blacklisted since 9/11 - more than 6900 consecutive days of blacklisting torture. Will Alito abolish state-operated Fusion Centers with a 99% failure rate (comparing terrorism-searches vs. terrorism-convictions). What about BLM protesters blacklisted for legal First Amendment activity. These innocent Americans lost rights also.

Fuck blmantifa

Ugh. Fusion center say beaver have heavy coat, say Gomez Addams pocket watch point to 25 o'clock, say hemlines go up, say mouse parts in McDonald's...conclude human trafficking on 4th Street.

I have a few suggested guidelines for the next public health crisis (and have no doubt there will be more now, every few years):

1. Any lockdown orders must follow state law. If the state law says an emergency expires after 30 days unless the legislature grants an extension, it expires after 30 days. The governor can't just issue a new order, or what would be the point of the 30 day limit?

2. No county or city level public health officer can issue any lockdown order against healthy people, only those confirmed infected and contagious. Any attempt to interfere with freedom of movement or commerce can only be ordered by the state governor, and only pursuant to state law. Governors have to stand for reelection, and have to consider the economic consequences of their actions, local health officers don't.

3. Any state or local official (including the governor) who exceeds their lawful authority should face federal civil rights charges. Malfeasance and overreach were rampant in 2020, where are the federal charges?

How about this there is no order that is unconstitutional? You know like that bastion of liberty Sweden. Who knew that Sweden is the bastion of liberty in 2020.

WHO FUCKIN KNEW

Or we could elect people who were competent at governing in the first place. Obama actually prevented an ebola outbreak. No lockdowns necessary.

So Obama prevented it how? C'mon dipshit

Very, very carefully.

Tony is incapable of posting without lying.

“Obama actually prevented an ebola outbreak”

Nope. A cool,Kant media just stopped reporting the numbers.

SCOTUS is a partisan political institution and can we please stop pretending otherwise?

Yes, you and your friends made it political. As you can’t imagine anything that isn’t political.

Regarding the abortion restriction, if they actually believed the lockdowns would only last 14 days as they originally said then the burden on access to abortion would have been negligible.

But they knew from day 1 they were never going to fully lift the lockdowns, so they had to fight the abortion restrictions on those grounds

Well you know all of the cool lawyers and judges say when there is pandemic your dictator governor can do whatever he wants and the constitution doesn't apply.

C'mon Sam you know those founders really meant that don't you.

A whole bunch of schmucks over at Volokh , you know the cool libertarians , also believe that.

Problem is the constitution doesn't have a suspension clause. And you've let it go 8 months now and we've elected a demented idiot who thinks he can cure Covid. He can't even finish a sentence .

Reason would do well to reject the MSM tendency to use unflattering photos of people in its articles. I didn't even recognize Alito from that photo, and after doing an image search, I'm not sure that any of the many, many images I've found are less flattering than this one.

And this is an article that refers to Alito in a positive light, even.

Gavin Newsom on line #1; sounds worried.

I'm happy to live in Florida.

Attn looters: not a good idea to start shit here

Yeah, in a nation built on genocide, slavery, Jim Crow, misogyny and all kinds of other human rights abuses, we just have never seen anything like Covid-19 restrictions.

Sarc? Stupidity? Lefty fantasy?

Oooh, this one might be Tony grade stupid.

Of course Slate called it "hyperpartisan". To the staff at Slate, the wetness of water and whether the sun rises in the east or the west are considered to be mildly partisan topics of discussion.

So what about Missouri suing the Communist Party over their germ weapons lab leak infecting the planet with a communist-scale health hazard? Have any other states budded cojones?

In a political movement based on redefining reality and economic fantasy, we just have never seen anything like respect for human decency.

I made 10k dollar a month doing this and she convinced me to try. The potential with this is endless. Here’s what I’ve been doing Please visit this site…. CLICK HERE FOR FULL DETAIL

I made 10k dollar a month doing this and she convinced me to try. The potential with this is endless. Here’s what I’ve been doing Please visit this siteby follow detailsHere═❥❥ Read More

The current crop of Marxists Democrats couldn't care less about rule of law or anything else that stands in there way. Thank you America for Joey who is about to show us the true meaning of lockdowns, isolation, economic shutdowns and the destruction of humanity. Other than Trump, and a few others, no one is stopping this fake pandemic fallout.

Sorry, but Alito concern for government overreach is limited only to issues he concerns important.

First, Alito is criticism of NV is a red herring. NV didn't ban religious expression or restricted the size to 50. It was INDOOR meetings are limited to 50. Outdoors 50+ were allowed.

Second, he himself has endorsed the idea of religious practices being subordinate to State's interest to protect the public through state sanctioned homicide. Dunn v Ray, he defended state right to commit homicide on its terms as superior to an individuals Muslim's religious practices. Even worse, he did for Budist what he refused for a Muslim.

This doesn't address the 50 person limit for indoor religious gatherings compared to the lack of such limitations on indoor entertainment gatherings.

Though it would have been amusing if the casinos had been told to set up the slot machines outside.

Most of these COVIS restrictions are unconstitutional. The closing of churches is but one example. Restrictions on private gatherings violate the First amendment guarantee of the right to assemble peaceably. There is no public health exception to the first amendment. ‘Stay At Home’ orders are a form of house arrest - without benefit of a trial or hearing. Also unconstitutional. Someone needs to challenge these in the courts.

Google is now paying $17000 to $22000 per month for working online from home. I have joined this job 2 months ago and i have earned $20544 in my first month from this job. I can say my life is changed-completely for the better! Check it out whaat i do..... Read More.

My state's governor has once again "ordered" certain businesses and activities shuttered for a 2 week period. People out of work, people unable to do their normal daily activities, just like before and it was ineffective in terms of the virus then, it will be now. What possible legal authority does a governor have to force a business to close its doors to its customers and tell me how many people I can have in my home?

The majority of these COVIS limitations are unlawful. The end of holy places is nevertheless one model. Limitations on private social events disregard the First revision assurance of the option to collect serenely. There is no general wellbeing special case for the main alteration. 'Remain At Home' orders are a type of house capture – without advantage of a preliminary or hearing. Likewise unlawful. Somebody needs to challenge these in the courts.

https://www.workant.io/

he lion's share of these COVIS restrictions are unlawful. The finish of heavenly places is by and by one model. Impediments on private get-togethers dismiss the First amendment confirmation of the choice to gather peacefully. There is no broad prosperity extraordinary case for the fundamental modification.

https://dealmarkaz.pk/jobs_sialkot-c356440

Learned Hand said that in a speech almost 80 years ago and it's still incredibly true.

The issue with the authoritarian politicians' response to covid isn't the they have tried and succeeded, it's that so many people have welcomed having their liberty restricted.

Please daddy, save me from the scary virus!

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29658 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. I have joined this action 2 moniths back and I have earned $31547 in my first month from this action.IPl I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it.

What I do......... Home Profit System

Tony is smarter than you.

As a full time student, you should consider a career at Shop Rite.

I've heard it's a great stepping stone to high paying jobs.

Like we didn't know that. Ever been to one of our parades?

I second this, I mean at least Rev I think is a parody account.

I get paid 75 bucks each hour for work at home on my PC. I never thought I’d have the option to do it however my old buddy is gaining 14k/month to month by carrying out this responsibility and she gave me how. Give it a shot on following website…. WORK24HERE

Lord have mercy...the sick level of entertainment I get from these comments.

And sadly just now I realized Tony is gay. I mean, with all the ass comments, I'm just pissed that I could have been laughing longer, harder, and more often, had I known.

"Tony is smarter than you."

Coming from someone of room-temp IQ.

You're being too generous

I've been to one of your parades.

It was gay.

I know right?

I know enough to stay far away from them because of all the noise they make and disease they spread.

A 3 year old is almost a million times less likely to have any Covids than an octogenarian.

But I'm pleased that by inference you don't have kids. That's an excellent trait for a Demorrhoid.

Sure, but how are we going to get rid of the Demorrhoids? We don't have enough helicopters. We'll probably need logchippers.

The 3 year-olds were a metaphor for Trump supporters.

Wow Tony, you got owned. That was really rough. Sorry, but it's obvious you didn't only think about Trumpers.

Having very few ebola cases is the same managing it well you simpleton.

Trebuchets are far more environmentally friendly than helicopters.

Remember, folks, *sustainable* purging.

He's using the Celsius scale.

Google is by and by paying $27485 to $29658 consistently for taking a shot at the web from home. I have joined this action 2 months back and I have earned $31547 in my first month from this action. I can say my life is improved completely! Take a gander at it

what I do.........work92/7 online

That's right, because people who have no drivers license, and thus never drive, get into accidents most rarely.

Thus, they are the best drivers. I learned that in my social science class, back in 2034.