Joe Biden Should Stop Bragging About the Violence Against Women Act

The Democratic nominee championed the law as a way to protect women. Instead, it hurt them.

When city police in Castle Rock, Washington, arrested Joel Darvell in April 2013, he stood accused of choking his wife, smacking his son in the face with a handgun, and firing the gun to the side of them during a drunken domestic rampage. After his arrest, he was charged with first- and second-degree assault with a firearm and fourth-degree assault. Darvell posted bail, meaning he spent that evening free.

His family—a 13-year-old daughter, a 17-year-old son he'd allegedly smacked with a gun, and their mother, the woman Darvell has been accused of drunkenly choking—spent the night in jail.

Their offense? Refusing to testify against the family's husband and father. He went free. His victims paid the price.

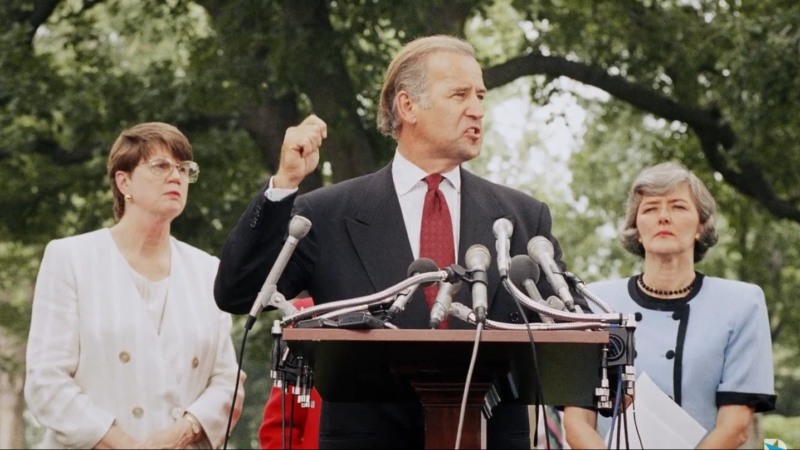

Arresting perpetrators of domestic violence against their victims' wishes is another lingering effect of 1990s crime measures. A handful of states started "mandatory arrest" policies earlier, but they really spread across the U.S. after the passage of the federal Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), part of the infamous 1994 crime bill. The man behind this piece of legislation was then-senator and current Democratic presidential nominee, Joe Biden.

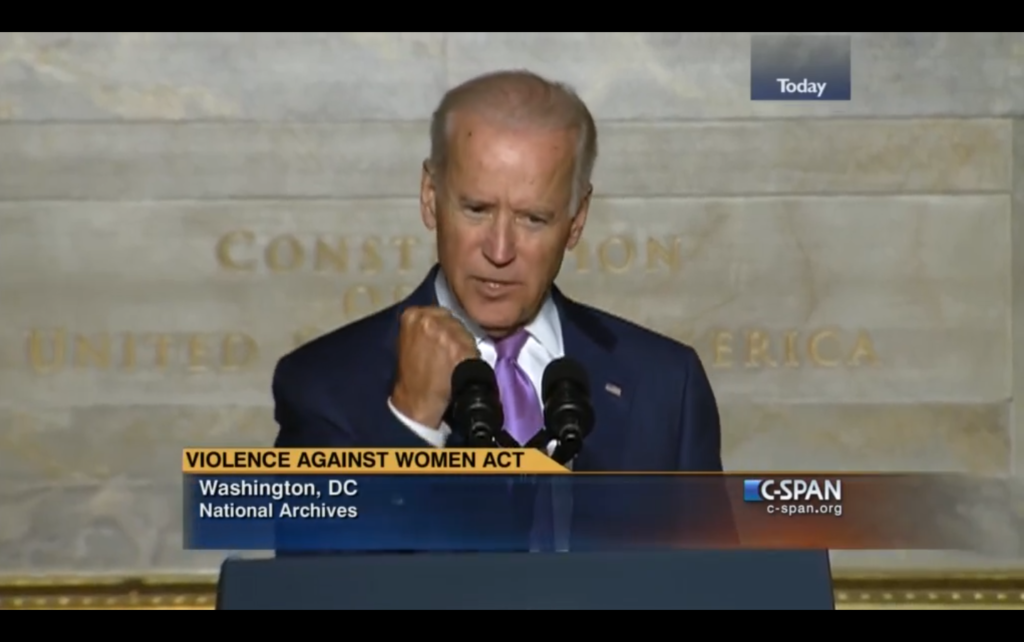

The parent bill, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994—signed into law by President Bill Clinton with enthusiastic backing from both parties in Congress—has since been disavowed by Democrats and Republicans, including both Biden and President Donald Trump. But Biden and the broader Democratic Party are still boasting in 2020 about VAWA. They shouldn't be.

VAWA was the product of activist agendas and political convenience, written and sold on ideas and evidence that were either dubious or outright debunked. Rather than providing concrete aid to those harmed by domestic violence, Biden's law funneled billions to police and prosecutors to enact policies that put women in greater danger—and said victims' wishes didn't matter when they conflicted with what the state thought best.

From Women Helping Women to Women Helping the State

In August, a Democratic National Convention press release declared that America has come far "in its attitudes and efforts to protect women against domestic violence, thanks to then-Senator Joe Biden's leadership on the Violence Against Women Act." The statement asserted that 30 years ago, "domestic violence was treated as a private matter, not a heinous crime," but "Biden believed it was time to do the right thing."

The idea that the U.S. ignored domestic violence until Biden and boomer feminists came along has become a popular one. But it doesn't square with the historical record, which shows not only that feminists have long prioritized stopping domestic abuse, but that there has long been a divide between those who believe that mandating aggressive police intervention helps women, and those who see law enforcement as doing more harm than good. Understanding that divide is necessary for understanding not only how VAWA came to pass, but why it has failed to accomplish its stated goals.

"Assaults and threats of physical violence against intimate partners have been illegal for centuries," noted lawyer Leigh Goodmark in The New York Times last year. "The Massachusetts Bay Colony outlawed wife abuse in 1641; by the late 1800s, a number of states had criminalized violence against a spouse." In the 19th and 20th century, "first wave" feminists were often motivated by concerns about women trapped in abusive marriages. These activists pushed for everything from women's suffrage and property rights to liberalized divorce laws to Prohibition, since it was commonly believed then that drunkenness was the main cause of abuse.

In the '70s, feminists again took up the cause of domestic violence. Initially, their activism was centered on measures like launching emergency shelters and mutual aid networks—solutions that didn't invoke the state. As Aya Gruber, a law professor at the University of Colorado Law School and former public defender, writes in her new book The Feminist War on Crime, "The nascent battered women's movement was radical and antiauthoritarian at its core." But fairly quickly, it "transformed from a radical antiauthoritarian movement into a propolicing, proprosecution lobby."

Some feminists objected to this approach, particularly women of color and others from groups who associated police more with perpetuating violence than providing protection. But their concerns were crowded out by the largely white feminist mainstream, who tended to treat domestic violence as almost solely an expression of patriarchal attitudes and misogyny. While the former argued that addressing things like housing, poverty, unemployment, bigotry, and mental health issues would help curb domestic violence, the mainstream coalesced around the idea that domestic violence happened because abusers were sexist, and the criminal justice system simply wasn't tough enough on them.

This was the backdrop for the development of the mandatory arrest policies and no-drop prosecution policies that would eventually ensnare Joel Darvell's family.

Historically, police didn't make warrantless arrests for misdemeanor crimes that did not occur in their presence. In the '70s, feminists started pushing to change this, with some early success. The first statewide mandatory arrest policy was passed in '77 in Oregon. (Washington, D.C., and 49 states now exempt domestic violence from this rule.)

Mandatory arrest policies say that when cops respond to domestic violence—spousal abuse, intimate partner violence, family violence—they must make an arrest if there's at all probable cause to do so. No-drop policies say prosecutors will take domestic violence cases as far as they can regardless of whether a victim wants their assailant criminally punished.

The idea was that removing victim discretion would benefit battered partners too afraid to cooperate with police, and removing police discretion would stop sexist cops from taking domestic violence lightly. But the story of why police officers didn't always make domestic violence arrests is more complex than this suggests. Some law enforcement officers may well have been the kind of chauvinist do-nothings the feminist narrative invokes. But police testimony repeatedly cited victims' wishes as the top reason for low arrest rates, a situation which left cops feeling frustrated and powerless to help.

Three trends around this time helped cement left- and right-wing support for addressing domestic violence as primarily a criminal justice matter.

First was the crime wave of the '80s and early '90s, and the preference for tough-on-crime policies that followed in politics. Second was a lawsuit against Torrington, Connecticut, brought by a woman who was partially paralized by abuse from her husband after repeated calls to local cops, who did nothing. The suit forced the city to pay out millions of dollars; fearing the same, some authorities saw mandatory arrest laws as a way to stave off legal liability.

Finally, feminist activists like Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin argued that violence against individual women wasn't just violence against individual women but a form of terorrism or hate that men perpetuated based on gender, and that the state not stopping this was a violation of women's civil rights. As Gruber wrote in The Feminist War on Crime, feminist lawyers convinced courts "that battered women had a right to state action. But it was one kind of state action—arrest. Within short order, this right became compulsory, and a battered woman could not waive the 'right' to her husband's arrest."

Further support for these schemes came courtesy of a research project, the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment. In 1981 and 1982, officers in the Minneapolis Police Department made mandatory arrests during some domestic violence calls and not others. In April 1984, researchers Lawrence W. Sherman and Richard A. Berk published a paper in American Sociological Review indicating that mandatory arrests helped decrease repeat domestic violence. Their results were widely publicized in mainstream media and cited by political figures. Police departments started allowing and encouraging domestic violence arrests, sometimes mandating them.

After the Minneapolis experiment, Sherman and his team conducted five similar but larger research projects, finding that—contra the first study—arrests often escalated violence over time, especially in districts with large black populations. Mandatory punishment schemes "make as much sense as fighting fire with gasoline," Sherman and two co-authors wrote in the 1992 book Policing Domestic Violence: Experiments and Dilemmas. At that point, the District of Columbia and 15 states mandated arrest in misdemeanor domestic battery cases.

Perhaps these policies would have just been a quick fad, as more and more research accumulated challenging their wisdom and suggesting they actually put women in more danger. But then came Joe Biden.

Joe Biden, Crime Panic, and Liberals for Mass Incarceration

The phrase "violence against women" first appears in the congressional record in 1982, when a Republican representative blamed both it and AIDS on pornography. That was the same year the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights reported to senators on the federal response to it and two years before President Ronald Reagan's administration put out a major task force report on family violence.

Tales of battered wives, real and fictionalized, filled popular media, while activists encouraged the view that the average case involved extreme violence followed by extreme law enforcement neglect. By the end of the '80s, American lawmakers commonly touted dubious data about domestic violence as fact. "Violence against women will occur at least once in two-thirds of all marriages," claimed Rep. Bob Carr (D–Mich.) in an October 1987 floor speech. "In this country, a woman is beaten every 18 seconds."

It was against this backdrop that Biden introduced his first version of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) in 1990. Biden had already latched onto criminal justice as a signature issue in the '80s, pushing harsher sentences, more police, and more prisons as a response to rising crime. This wasn't just a policy response; it was a political strategy designed to respond to Republican attacks positioning Democrats as soft on crime. By 1994, Biden could be found bragging that "the liberal wing of the Democratic Party is now for 60 new death penalties," and "the liberal wing of the Democratic Party is for 125,000 new state prison cells."

Like so much of the era's tough-on-crime rhetoric, Biden's case for VAWA was littered with panicky pronouncements unrooted in fact. "During her lifetime, one in five women will be raped," Biden told Senate colleagues in January 1991, previewing a junk statistic that he would rebrand during his vice presidency as one in four women. "Last year, more women were battered by their spouses than were married," he said (again without citation or evidence), adding that "authorities are more likely to arrest a man for parking tickets than for beating his wife."

Research showing that aggressive arrest and prosecution policies actually increased violence against some women, particularly black women, was well-publicized by this point. Nevertheless, Biden's first two drafts of VAWA encouraged states to adopt both no-drop prosecution and mandatory arrest in domestic violence cases.

The version that eventually passed did not include the words no-drop. But it still encouraged aggressive action by providing state, local, and tribal governments with money to "implement mandatory arrest or proarrest programs," to "strengthen…prosecution strategies," and to ensure "more widespread…prosecution." It also conditioned many of VAWA's grants on government's certifying "that their laws or official policies encourage or mandate arrests of domestic violence offenders" and of people "who violate the terms of a valid and outstanding protection order" and stipulated that priority would be given to entities that "demonstrate a commitment to strong…prosecution of cases."

The Violence Against Women Act was signed by Bill Clinton in September 1994. By 1996, an American Prosecutors Research Institute survey found that large jurisdictions showed "a pronounced willingness of prosecutors to move forward in cases in which victims do not participate as witnesses and to rely on non-traditional methods to ameliorate the litigation dilemmas presented by victim absence." Prosecutors also "reported a high percentage of cases in which the victim would not serve as a witness."

This is how we wind up with cases like the Darvells, through policies that were either built into VAWA or encouraged by its language. After more than 24 hours in jail, Darvell's wife and son each agreed to testify against him and were set free. But his 13-year-old daughter wouldn't give in and remained locked up another night. Finally, after two nights in jail, she appeared in court, shackled at the wrists and ankles. She told the judge she would testify against her dad if she could go home.

After his family got out of jail, Joel Darvell was offered a plea deal. Later that year, the case's lead police officer was awarded for his work at the city's Justice and Hope Conference.

The kids' involvement in this story makes it stand out. But there are myriad stories of women being arrested or jailed for refusing to testify in domestic violence cases against their partners, and surely countless more cases where the threat of this very real possibility has been used to coerce victim testimony. By 2009, "every state ha[d] some form of pro-arrest policy and, as of 2004, at least twenty states and the District of Columbia mandated arrest in cases involving domestic violence," notes Goodmark in her paper Autonomy Feminism.

A critic of mandatory arrest and no-drop prosecution from a feminist perspective, Goodmark—author of the 2018 book Decriminalizing Domestic Violence—suggests that "at their core, these policies reflect a struggle over who will control the woman who has been battered—if the state does not exercise its control over her by compelling her testimony, the batterer will, by preventing her from testifying. Hard no-drop policies express the state's belief that it has a superior right to intervene on behalf of the woman who has been battered in service of both the woman's needs and the state's objectives."

Big Government vs. Domestic Abuse

VAWA was, at its core, a funding bill, designed to dole out grants to a variety of programs. Specifically, it authorized $1.62 billion in federal funding for related programs over six years. "The majority of these funds will assist police and prosecutors at the state and local levels," Rep. Anna Eshoo (D–Calif.) explained in October '94.

In the original and subsequent extensions, VAWA funding for shelters and non-law enforcement support for victims was miniscule compared to amounts going toward supporting police, prosecutors, and courts, or to general "awareness" raising. "More than 50% of the current VAWA allocation is directed to training and support of police and prosecutors," University of Miami law professor Donna Coke noted in 2014.

The largest portion gets dished out as Stop Violence Against Women grants, which cannot go to nonprofits or religious groups providing services, only to states and territories. Governments who get these grants must agree to use 30 percent for services for victims of abuse, while 55 percent must go to prosecutors, law enforcement, and courts. Another 15 percent is discretionary.

Much of the money continues to go toward training cops and other authorities on how to handle domestic violence cases despite the fact that research has found little evidence that it makes a difference. For instance, a federally funded study of VAWA training, published in 2000, found "training produced no change in attitudes toward [domestic violence], had no effect on an officer's opinion toward mandatory arrest, and that the training did not make it easier for an officer to identify the perpetrator or to determine whether victims wanted to cooperate with officials to end the violence. Additionally, the DV training did not change the length of time the police officers spent at the scene, acceptance of cases for prosecution, or the number of resulting convictions."

The Government Accountability Office and other official watchdogs have repeatedly warned of problems in VAWA grant program overlap, data collection, oversight, expenditures, and effectiveness. The grant programs have also been plagued with waste, fraud, and embezzlement, with a number of recipients criminally charged in recent years.

But perhaps the biggest flaw with the grant programs is that they make it nearly impossible for victims of abuse to get services without the state getting involved. For undocumented immigrants, sex workers, drug users, people worried about Child Protective Services involvement, or anyone with reason to be distrustful of cops or other authorities, this can serve as a serious deterrent to getting help. VAWA was sold as a package of victim support. Yet support funneled through the offices of state attorneys general and an alphabet soup of government agencies is support that many victims cannot or will not access.

Not all of VAWA was counterproductive. For instance, several provisions addressed legal barriers for immigrants stuck in abusive marriages. But the legislation's benefits have been outweighed by policies that have proven destructive—or unconstitutional.

A central part of VAWA was creating a special civil right of action for female victims of violence to sue their assailants in federal court. The rhetoric justifying this was heavily influenced by feminists who asserted that many if not most cases of rape, sexual assault, domestic violence, and other violence against women were hate crimes that men perpetrated against women based on their sex. Congress invoked the Commerce Clause, which gives it jurisdiction to regulate matters of interstate commerce, in explaining why it had the power to pass this law change.

Biden said in a June 1994 Senate floor speech that his "hope" here was "not only will the man go to jail if the woman can prove she was a victim of violence because of her sex, she can take his car, his house, his savings account. She can be empowered not to have to wait for the state to proceed."

The action was rarely used, however, and in 2000, the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional. If VAWA logic was allowed to stand, Congress could "use the Commerce Clause to completely obliterate the Constitution's distinction between national and local authority," justices wrote in a 5-4 decision.

That wasn't the only part of VAWA that attempted to make domestic violence a federal criminal matter, instead of one best handled by state and local law enforcement and social services. VAWA created three new federal criminal offenses: interstate domestic violence, interstate violation of a protective order, and a federal stalking charge. (A later extension would also add federal cyberstalking.)

Unlike other VAWA policies, these don't seem to have significantly contributed to driving up incarceration. Their flaw falls in the other direction: so little use—and use in cases that would clearly be illegal under state laws already—suggests they were utterly unnecessary.

Data collected by Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University shows that since 2000, federal authorities have never convicted more than 18 people in one year on interstate domestic violence charges, with most years seeing under 10 convictions. There were three in 2015, for instance, and four in 2010. For interstate violation of a protective order, none of the past 20 years have seen more than five convictions (a high point that came in 2000). Six years saw just one conviction, and four years saw none at all. Half of the time, two or fewer prosecutions were even opened annually. The most active charge has been stalking, with 18 convictions last year and 14 so far this year. In total, 161 people were convicted on federal stalking charges between January 2000 and August 2020.

Meanwhile, evidence suggesting VAWA actually decreased violence against women is, at best, murky. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the rate of intimate partner violence dropped from 15.5 victims per 1,000 women and 2.8 victims per 1000 men in 1995 to 5.4 women and 0.5 men per 1,000 in 2015. That's a decrease of about 65 percent for women and 82 percent for men.

However, this occurred during a period where crime in general, including violent crime and sexual assault, had been drastically falling. Between 1993 and 2019, for instance, national crime data show a 64 percent decrease in violent crimes across the board and a 30.4 percent decrease in sexual assaults and rape. By 2019, this had ticked up slightly, but was still down 59 percent for violent crime and 26 percent for sexual assaults.

What's more clear is that mandatory arrest and prosecution policies haven't helped.

One statistic stands out: "Mandatory arrest laws are responsible for an additional 0.8 murders per 100,000 people. This corresponds to a 54 percent increase in intimate partner homicides." That's from a 2008 paper by Radha Iyengar Plumb, now a research director at Google and a health research fellow at Harvard University when she conducted the domestic violence research. In the paper, published in the Journal of Public Economics, Iyengar found that in states with mandatory arrest policies, "homicides of males by their female partners are not significantly affected" but "intimate partner homicides of females increase about 50 percent"—a rise she attributes to mandatory arrest policies.

Even when disaster doesn't strike, the outcomes aren't great. In Milwaukee, doubling the number of domestic violence prosecutions meant "the time to disposition doubled, conviction rates decreased, the level of pre-trial crime increased, and victim satisfaction decreased," according to a 2006 study published in Criminology & Public Policy. Authors Robert C. Davis, Barabara E. Smith, and Bruce Taylor concluded that "the good intentions of policymakers needs to be coupled with a realistic expectation of what can be accomplished by the criminal justice system."

More recent research, published in 2015, found evidence that mandatory arrest laws may depress abuse victims' calls to the police for help in the first place.

That same year, Sherman—the man behind the Minneapolis mandatory arrest study so touted in the '90s—published the results of a followup look at 1,125 cases first studied in 1998. Victim whose partners were arrested and jailed were 64 percent more likely to have died (of any cause) in the intervening years, with the effect size much stronger for black women than white women (98 percent higher versus 9 percent). "The magnitude of the disparity strongly indicates that mandatory arrest laws, however well-intentioned, can create a racially discriminatory impact on victims," wrote Sherman in the March 2015 Journal of Experimental Criminology.

There's also evidence that mandatory arrest policies have led to more victims being arrested. If they respond to the abuse by fighting back physically, or even if their partners just say that they did, police often feel obligated to arrest both parties.

In Washington state—one of the first to enact a mandatory arrest law, in 1984—women were soon arrested in 50 percent of all domestic violence cases in which an arrest was made.

Nationally, the dual arrest rate in domestic violence cases is about 7 percent, though in some states, such as Connecticut, it's still as high as 20 percent. In California, women accounted for 5 percent of all felony domestic violence arrests in 1987—just before the state's mandatory arrest law passed—but, by 2000, this had risen to 18 percent, DOJ-funded researchers found.

"The existence of mandatory arrest laws (but not preferred arrest laws) significantly increased the likelihood of dual arrest," a 2007 report to the DOJ determined. "Dual arrest was significantly more likely to occur in cases involving same sex couples as opposed to heterosexual couples." However, cases in mandatory arrest states were "more likely not to end up in conviction than cases that take place in states with discretionary arrest laws."

Still, lawmakers have walked back their positions on these policies only slightly. For instance, they changed language from requiring grant recipients to mandate arrest to encourage or mandate arrest, and eventually to just encourage. But it's not clear this made much difference. As of 2020, 25 states had mandatory arrest policies, according to Alayna Bridgett writing in Health Matrix: Journal of Law-Medicine.

VAWA's Legacy: Bad Statistics, Bad Policies, and Little Help for Victims

Biden's role in all of this may indeed reflect a genuine desire to help women. But it also reflects his longtime role as Democrats' for-better-or-worse standard-bearer—the party operator willing to go all-in on whatever centrist ideas have captured the zeitgeist and to give a folksy, do-gooder veneer to all sorts of ultimately ugly policies. In the years since, he has moved seamlessly from mischaracterizing fears about domestic violence to backing counterproductive and ineffective responses to more modern moral panics, like campus sexual assault. And he has continued to display a tendency for elevating faddish interpretations of progressive feminist advocacy that turn out to infantilize women, driving up their arrest rates and placing them in greater danger—all while portraying himself and the state as their saviors.

During his tenure as Barack Obama's vice president, Biden showed no signs of having learned from his days exploiting fears of crime. From his perch in the administration, Biden helped expand a federal war on "sex trafficking" that largely arrested consenting sex workers and their clients. An even bigger focus—for Biden in particular—was on campus sexual assault.

Obama and Biden ostensibly set out to improve the way campuses responded to sex crimes and sex-based harassment by making changes to the enforcement of Title IX, the law governing sex discrimination in education, along with public awareness initiatives.

But the result was to create campus kangaroo courts that ignored the rights of the accused, crackdowns on professors' speech, and policies that encouraged administrators to pursue Title IX violation charges against students even when alleged victims said they didn't want it or that nothing had happened—much like VAWA. Meanwhile, there's no evidence that students were made safer or that campus victims feel they've started being treated more fairly.

In these efforts, dubious statistics continue to prop up dubious policies. As with the war on domestic violence, "the campus rape crisis was based not on changed circumstances but on increased preoccupation with an existing problem," notes Gruber in her book. And like that earlier episode, this one was frequently justified with bad research. In this case, the now-debunked work of psychologist David Lisak, which said most sexual consent violations on campus were committed by serial predators, was used to justify things like dismissing due process and instituting what are essentially no-drop Title IX inquiries.

In one particularly tone-deaf effort, Biden spearheaded the "It's On Us" initiative which told college men it was their duty to protect women who were drinking from sexual advances. "In a surprising twist," writes Gruber, "the feminist mantra that rapists cause rapes morphed into a decidedly less feminist notion that boys must protect girls from drunk or unwise sex."

Today, Biden's continued embrace of VAWA and an enhanced Title IX suggest he's learned very little about either criminal justice or feminism since the '90s.

His 2020 campaign website draws a direct throughline from VAWA to the Title IX initiatives to his future work, promising that, as president, Biden would once again bring renewed focus to enforcing and strengthening Title IX and laws against online harassment, sexual assault, domestic violence, and "dating violence."

"Dating violence" has become the latest frontier for VAWA expansion. Every few years since its original passage, VAWA has been expanded via "reauthorizations" that continue to make the law more powerful and far-reaching. "VAWA's power is that it gets stronger with each reauthorization," Biden tweeted in February 2019.

On the 26th anniversary of VAWA's passing, Democratic leaders again praised the bill and called for its expansion. They're currently seeking to apply VAWA's ban on gun ownership by people found guilty of certain crimes against spouses or domestic partners to those found guilty of offenses against any dating or sexual partner, too. They're also pushing the International Violence Against Women Act, which Biden has embraced.

But it's not just Democrats who are devoted to this law. In September 2020, the U.S. attorney's office said it would be "making the investigation and prosecution of federal domestic violence crimes a priority." VAWA isn't going away in 2021, no matter who becomes president.

VAWA's reauthorization is one of the American Bar Association's (ABA) "legislative priorities," the group wrote in August 2020, endorsing increased efforts to "restrict adjudicated abusers' access to firearms, closing "the 'boyfriend loophole' that allows abusers not married to their victims a functional free pass from surrender provisions," and creating "victim-defined innovations to serve as alternatives to criminal justice penalties."

The ABA's simultaneous focus on fixing flaws in past versions of the law while inserting new ways to expand (and misfire on) federal crime control is a common theme.

In recent years, Democrats have come to disavow much of the 1994 crime bill, and Obama and Biden even dismantled a few of its worst components. But VAWA has been almost wholly exempt from this reconsideration and reform.

It's time for this to change. As the COVID-19 pandemic brings renewed focus to the needs of people in abusive or volatile domestic situations, it's imperative that we don't repeat these same mistakes, forcing victims to bear the consequences of domestic abuse in the name of political gain. Joel Darvell's family didn't deserve to be punished for his actions, but as long as the ideas that drove VAWA remain law, it's victims who will continue to pay the price.

Any reauthorization of VAWA will further bind support for survivors of abuse, rape, and other forms of violence to federal whims, as well as to police, district attorneys, and judges. It's time we chucked this bad law and actually listened to victims about what they want and need.

CORRECTION: This original version of this piece contained a quote about a woman who would not testify against her abuser. The quote, from a Senate floor exchange between Biden and Sen. Arlen Specter, was misattributed to Biden and has been removed.

Show Comments (179)