Massachusetts and Alaska May Join Maine in Letting Voters Rank Their Choices

Two November ballot initiatives would introduce ranked-choice voting in two more states.

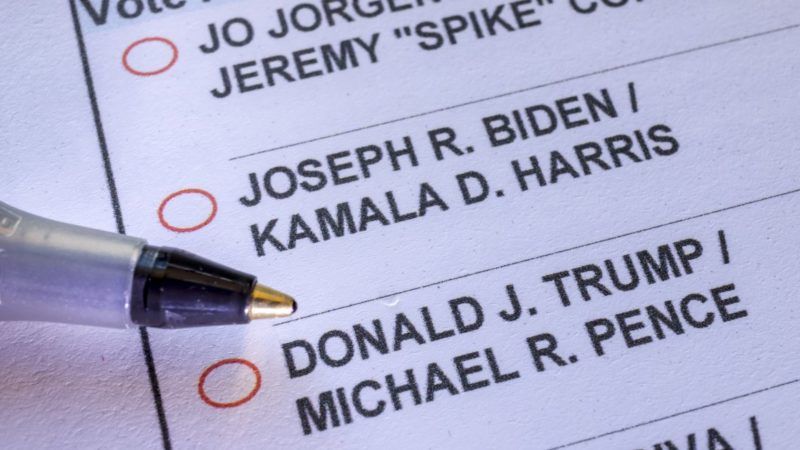

Voters in Massachusetts and Alaska will decide in November whether they want to implement ranked-choice voting for some of their state races.

If voters approve, they'll join Maine, which in November will be the first state to use ranked-choice voting for the presidential race.

In ranked-choice voting (sometimes called "instant runoff voting"), citizens don't just select one of the candidates for an office (though they can if they want to). They are permitted to rank each of the candidates on the basis of preference.

To win a ranked-choice election, one must receive more than 50 percent of the vote, not just a plurality. If no candidate has a majority, the candidate with the least votes is eliminated from contention. Then the votes are tallied again. If you ranked the eliminated candidate as your first choice, your second choice is instead tallied as your vote. And so the process goes until a candidate gets more than 50 percent.

In Maine, voters approved a proposition to introduce ranked-choice voting there for some state and federal elections in 2016. The state's Republican Party has been fighting it ever since, unsuccessfully. In 2018, ranked-choice voting contributed to the ouster of a GOP incumbent.

In Massachusetts, Question 2 will ask voters if they want ranked-choice voting for state officials and lawmakers, members of Congress, and some county offices. It would not implement ranked-choice voting in presidential races.

In Alaska, Ballot Measure 2 combines ranked-choice voting with open primaries. If it becomes law, candidates for state or congressional offices will first run in a single open primary where candidates for each office all face each other, regardless of party. After the vote, the top four (regardless of party) will face each other again in the general election. There voters will have the option to rank the four candidates for each seat, and then the rules of ranked-choice voting will be followed.

Why bother with such a complicated system? Proponents argue that under ranked-choice voting, you aren't "throwing your vote away" by supporting a third-party candidate and you don't have to feel beholden to the two-party model. In Maine, for example, voters will be able to vote for Libertarian candidate Jo Jorgensen or Green candidate Howie Hawkins and still also support either Joe Biden or Donald Trump. Research from FairVote, an activist organization supporting and promoting ranked-choice voting, found that voter turnout trends upwards in cities that have implemented ranked-choice voting.

All of this may explain why the state Libertarian Party affiliates in both Massachusetts and Alaska are supporting these ballot measures.

In Maine, voters have consistently shown support for implementation. But in Massachusetts, polling is currently divided almost evenly between support and opposition, with more than a quarter of voters undecided. In Alaska, it's polling ahead, 59 to 17 percent. Even so, the most recent poll had about a quarter of the voters undecided.

Ranked choice is not perfect, and it comes with its own set of frustrations. If you support only one of the candidates and that candidate does poorly, then your vote can get tossed out and mean nothing, just like in a winner-takes-all elections. It doesn't even necessarily make it easier for a third-party candidate to win. But it does mean that major party candidates cannot simply ignore the interests of more independent voters and run simply by appealing to their bases. Those independent voters' second choice might be what determines the election.

Show Comments (64)