America's Debt Will be Twice the Size of the Economy by 2050

The Congressional Budget Office warns that higher levels of debt will slow economic growth significantly in the years ahead.

If you're getting tired of unrelentingly bad news about the national debt—well, I have some terrible news.

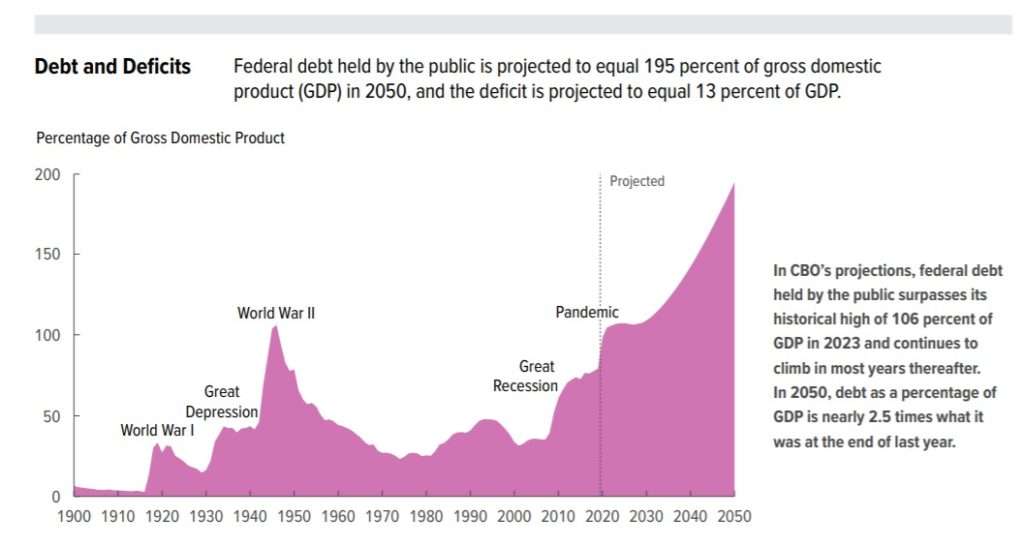

Today the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released a 30-year budget projection. By 2050, the number-crunching agency now says, the national debt will grow to 195 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). That's 45 percentage points higher than the CBO was projecting last year. What it couldn't foresee, of course, was the COVID-19 pandemic and the expensive federal response to it, which has pushed the national debt to nearly 100 percent of current GDP.

The national debt is expected to hit 107 percent of GDP—matching the record high set during World War II—by 2023:

Rising debt levels will "increase the risk of a fiscal crisis—that is, a situation in which investors lose confidence in the U.S. government's ability to service and repay its debt, causing interest rates to increase abruptly, inflation to spiral upward, or other disruptions," the CBO warns. "It would increase the likelihood of less abrupt, but still significant, negative effects, such as expectations of higher rates of inflation."

A national debt nearly twice the size of the economy will put a significant damper on long-term economic growth. The CBO now projects average growth of just 1.6 percent annually over the next 30 years. That's almost a full percentage point less than the 2.5 percent average growth rate during the past 30 years.

In short, Americans face the prospect of decades in which living standards increase at a slower rate. Businesses will likely have a harder time expanding, and the federal government will have an even harder time balancing its wildly off-kilter finances.

Although the coronavirus response has driven this year's budget deficit and the short-term national debt projections to higher-than-expected levels, the biggest problem between now and 2050 are the entitlement programs that will consume ever-larger shares of the federal budget.

While Social Security and Medicare spending are both projected to grow faster than federal revenue over the long term, another problem set to emerge in the 2030s and 2040s is the cost of paying for the national debt itself. As the country's debt load becomes heavier, the interest payments on the debt will become one of the federal government's biggest expenses, the CBO says.

"This current path will lead to insolvent trust funds and unsustainable levels of debt, prompting slower income growth, growing interest payments, and increasing the risk of fiscal crisis," Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said in a statement.

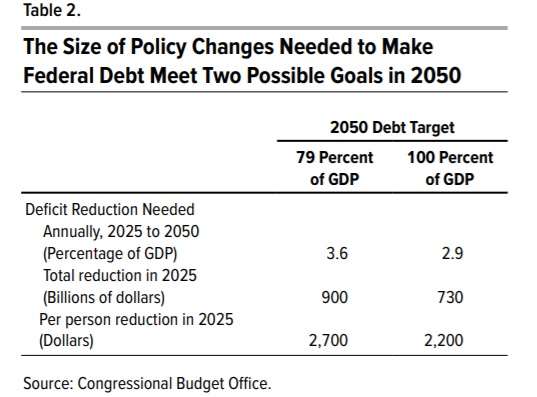

Reducing the size of annual budget deficits and getting the national debt under control will be no easy task. In order to merely bring the national debt down to 100 percent of GDP by 2050, the CBO estimates that Congress would have to implement policy changes—spending cuts, tax increases, or both—equal to about $730 billion (or 2.9 percent of GDP) by 2025.

That would be the same as cutting roughly half of all discretionary spending in last year's federal budget. And the longer Congress waits to take action, the larger that number will become.

As is always the case when discussing the long-term debt and deficit problems facing America, younger generations stand to lose if nothing is done in the near future. "Delaying policy changes would reduce the well-being of younger generations (compared with their well-being if policy changes occurred earlier)," the CBO warns. "Moreover, the farther in the future that a policy change occurred, the more the well being of older generations would be improved and that of younger generations would be worsened."

And, of course, none of this accounts for the possibility that spending could continue to increase above current baselines in the near future. Both President Donald Trump and Joe Biden have indicated that they will hike spending and add to the debt.

The bad news, it seems, will keep coming for a long while.

Show Comments (137)