Alone Together in the Pandemic

How we lost our social spaces and how we found them again

The past is a different country, one I used to live in.

In that country, as I remember it, people moved about and met with others freely, passing close to strangers on the sidewalk, wearing gloves and scarves only when the weather required it. They rode crowded buses and packed subway trains, commuting to their offices so they could sit through meetings in close proximity to their yawning colleagues. They stood in lines and watched kids climb on playground equipment. They went to restaurants with dates and had intimate conversations over dinners prepared by someone else, delivered by platoons of waiters whose hands touched each and every plate. They shared sips of expensive cocktails with fussed-over garnishes containing liquors imported from all over the world. They propped themselves up on comfortingly scuzzy stools at crowded dives, drinking cheap beer as other patrons unthinkingly brushed against them. They watched sports, and they played them.

In that country, people sweated out their frustrations in gyms, sharing weights and treadmill grips. They watched suspenseful movies in darkened theaters, never knowing who might be sitting nearby, breathing in unison as killers stalked through crowded streets onscreen. They hugged each other. They shook hands.

They gathered together, to celebrate, to mourn, to plan for a future that seemed, if not precisely knowable, likely to fall within expected parameters. And, though it seems foreign now, they treated each and every one of these moments as ordinary and unremarkable, because they were.

No longer. Over the course of a few weeks in March, America, along with much of the Western world, became a different country. A novel coronavirus was spreading via physical proximity. So in order to slow its transmission, the places where people gathered together—bars, restaurants, gyms, stadiums, movie theaters, churches—were closed. Workers were sent home from offices. Much of the populace was put into lockdown, under orders to shelter in place. People were effectively sent into hiding. What they were hiding from was each other.

The toll taken by the virus and COVID-19, the deadly disease it causes, can be measured in lives, in jobs, in economic value, in businesses closed and plans forgone. That toll is, by any accounting, tremendous—more than 74,000 dead in the U.S. by the first week of May, more than 33 million unemployed, an economy that may shrink by 20 percent or more—and in the coming weeks and months, it is certain to rise.

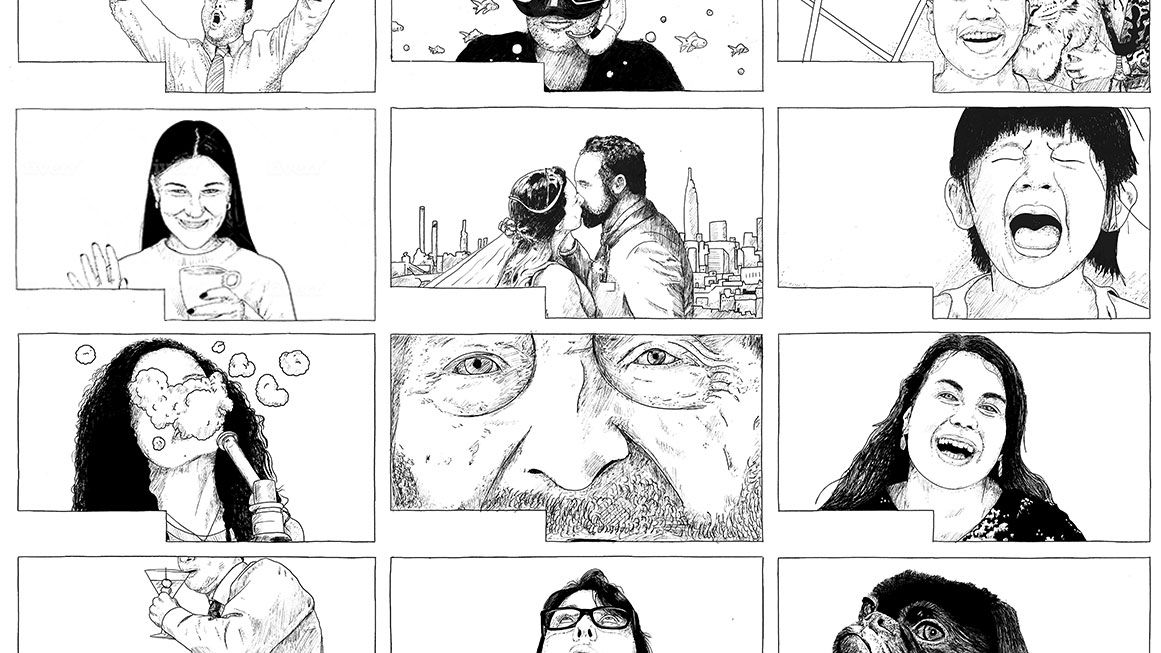

As lockdowns swept the country, we lost something else, too, something harder to measure: connection, intimacy, the presence of others, the physical communities of shared cause and happenstance that naturally occur as people go about their lives. We lost our social spaces, and all the comforts they brought us. Yet just as quickly, we went about finding ways to reclaim those spaces and rebuild those communities, by any means we could.

Friendship Machine

Among the first casualties of the pandemic were sports. After a player for the Utah Jazz tested positive for COVID-19 in early March, the National Basketball Association (NBA) suspended its season. Major League Baseball quickly followed, canceling spring training and postponing the start of the regular season indefinitely. In the space of a few days, every other professional sport currently in season followed suit.

Athletics facilities of all kinds—from YMCAs to Pilates studios—closed their doors, with no idea when they would reopen. In multiple cities under lockdown, public officials singled out pickup games as prohibited. This was the country we were suddenly living in: You couldn't watch sports. You couldn't play them. Group exercise of almost every kind was all but forbidden.

Games and athletic pursuits have many purposes. They strengthen the body and sharpen the mind. They pass the time. And they build bonds of loyalty and friendship, camaraderie and common purpose. In short, they're a way of making friends. In the days and weeks after the shutdowns, people found ways to quickly, if imperfectly, replicate or replace all of those things.

With facilities closed, fitness centers began offering online classes and instruction. Vida Fitness, a major gym chain in Washington, D.C., rolled out virtual memberships, featuring a regular schedule of live workouts and a library of full-length instructional videos. Cut Seven, a strength-focused gym in D.C.'s Logan Circle neighborhood owned by a husband-and-wife team, started a free newsletter devoted to helping people stay in shape from home. All over the country, group Pilates and yoga classes moved to videoconferencing apps like Zoom, with individual lessons available for premium fees. A mat and a laptop in a cluttered bedroom isn't quite the same experience as a quiet studio with fellow triangle posers, but it beats nothing at all, and has even become a kind of aspirational experience. We're all Peloton wives now.

Competitive sports went virtual as well. The National Football League held its annual draft online. Formula One organized a "virtual Grand Prix" around the F1 video game, featuring turn-by-turn commentary from professional sportscasters. Sixteen pro basketball players participated in the NBA 2K Players Tournament, which pitted the athletes against each other on Xboxes, playing an officially licensed NBA video game, with a $100,000 prize going to coronavirus relief charities of the winner's choice. Phoenix Suns guard Devin Booker won and split the money between a first responders fund and a local food bank.

With traditional sports sidelined, video games stepped into the spotlight. The World Health Organization, which in 2019 had officially classified gaming addiction as a disorder, joined with large game publishers to promote playing at home during quarantine. On March 16, as state-based lockdowns began in earnest, Steam, a popular hub for PC gaming, set a record for concurrent users, with more than 20 million people logged in at once. A week later, it set another record, with 22 million. Live esports events were canceled, but professional players of games like League of Legends, Overwatch, Call of Duty, and Counter-Strike all continued online.

People weren't just playing; they were watching. In April, viewership of Overwatch League events on YouTube rose by 110,000 on average. Twitch, the most popular video game streaming platform, set new audience-number records. Watching other people play video games, like watching sports, became a way to pass the time.

Video games may not exercise the body—that's what Zoom Pilates is for—but they can sharpen the mind and help form lasting virtual communities.

That has certainly been the case for EVE Online, one of the oldest and most successful large-group online role-playing games in existence. EVE players build and control massive fleets of ships while participating in a complex virtual economy. More than most of its peers, the game's story and gameplay are driven by players, who coordinate among themselves to form in-game alliances and trade goods and services, developing complex supply chains and running trading outposts. Many of the game's core features, including its Alliance system, which allows player-corporations to band together to maintain in-game sovereignty, started as player innovations. In some ways, it's less a game and more of an economic simulator and an experiment in virtual self-governance.

EVE has been going since 2003. But in the COVID-19 era it has seen a "massive and unprecedented change in the number of players coming into the game," says Hilmar Pétursson, the CEO of publisher CCP Games.

The pandemic lockdowns may have brought new players in, but Pétursson believes it's the community that will keep them coming back. The game's developers recently commissioned player surveys to find out what motivates them to play. "We had this thesis that people would join for the graphics, and stay for the community," he says.

It worked even better than the game makers expected. "Self-reported, the average EVE player has more friends than the average human on Earth," Pétursson says. In player surveys conducted in November and December 2019, roughly three-quarters said they had made new friends through the game, and that those friends were very important to their lives. Their data, he argues, shows that "people were making real, deep, meaningful friendships within the game."

"EVE is made to be a very harsh, ruthless, dystopian game," he says. "It seems that condition pushes people together to bond against the elements, and against their enemies. That creates real, deep, meaningful friendships." What the developers eventually realized, he says, was that "actually, we were making a friendship machine."

That has lessons for a world in which everyone is suddenly shut inside their homes. "What we have been seeing from EVE is that physical distance doesn't mean isolated at all," Pétursson continues. A game like EVE encourages players to band together to coordinate complex group actions, from space wars to elaborate trading operations. In a time where everyone is separated, that sort of loosely organized teamwork offers "a proven way to maintain social connection."

Sports may be benched. Gyms may be closed. Pickup games may be illegal. Yet people are still finding ways to keep their bodies fit, to compete with each other in games of skill, to pass the time by watching others do so, and to bond in the absence of physical proximity.

Let's Not Go to the Movies

Not every communal experience lost to the pandemic will return. And those that do might be forever changed.

Few social experiences are as common as going to the movies. Even as streaming services have made at-home viewing more convenient than ever, theatrical viewing has persisted and even thrived. In 2019, global box office returns hit $42.5 billion, a new record. But it's hard to have a global movie business when most of the places where people go to see movies around the globe are shut down. Even in boom times—despite the record box office numbers—making and showing movies is a precarious business. In the midst of a pandemic, it's nearly impossible.

The lockdowns not only shut down movie theaters, which as large gathering places represented potential vectors of transmission; they also shut down film productions, including some of the biggest movies in the works: a fourth Matrix film, all of Marvel's next big superhero movies, yet another sequel to Jurassic Park. Meanwhile, with theaters closed all over the planet, release dates for films that were already complete were pushed back by months or postponed indefinitely. The biggest impact was on tentpole films—the expensive-to-make franchise sequels whose budgets are predicated on making billions at the box office. Originally set to open in April, the 25th James Bond film, No Time To Die, was bumped to November. The new Fast and Furious film, originally set for May 2020, was moved back to May 2021. A long-gestating Batman follow-up was pushed to October of that year. The dark knight wouldn't return for a while—if he ever returned at all.

With theaters empty and nothing on the release calendar, the situation looked grimmer than a gritty reboot. Under the best-case scenario, theatrical grosses are expected to drop 40 percent this year. That's if theaters reopen at all. Most movie screens are owned by a quartet of companies—AMC, Regal, Cinemark, and Cineplex—all of which were in difficult financial positions when the year began. Even the healthiest of the bunch, AMC, was already deep in debt. In April, just weeks after analysts downgraded its credit rating, the company borrowed another $500 million in order to be able to survive in case of closures through the fall. But this was a risky maneuver. If closures persist long enough, industry analysts warned, AMC could end up going bankrupt. And if AMC bit the dust, the other big chains might follow.

Even worse, from the theaters' perspective, was that movie studios were starting to break the agreement that had long propped up their entire business model: the theatrical window. Studios gave movie theaters exclusive rights to air first-run productions—typically for about three months—before showing them on other platforms, such as video on demand. For years, theater chains had forcefully resisted even the smallest attempts to encroach on their exclusivity. But with theaters closed, the deal was off: Universal released several smaller genre films, including The Hunt and Invisible Man, to video on demand just weeks after they debuted in theaters. Bigger-budget films followed. Trolls World Tour, an animated family film, skipped theaters entirely. And Disney decided to release Artemis Fowl, a $125 million Kenneth Branagh–directed fantasy in the mold of Harry Potter, directly to its new streaming service, Disney Plus.

This was an existential threat to theater chains—and to the modern theatrical experience. Would cinemas -survive?

"I would not invest my kid's piggy bank in any of the big-box, generic movie theaters, as very few general-audience members are brand loyal to a specific theater chain, and these same viewers will not make the efforts to go see a movie in theaters if it is going to be available in their home days later," says Dallas Sonnier, CEO of the independent production company Cinestate, in an email. (Disclosure: I appear on Across the Movie Aisle, a podcast published by Rebeller, a Cinestate brand.) Cinestate specializes in genre fare made with modest budgets: Its best-known releases are the neo-western Bone Tomahawk, with Kurt Russell, and Dragged Across Concrete, a noirish crime thriller with Mel Gibson and Vince Vaughn, which had limited theatrical showings but found receptive audiences in home viewing. That gives Sonnier a unique perspective on the industry's current predicament.

"Sure, there will be a brief surge of pent-up demand," he says, "but that will wane over time, as big theater chains join the ghosts of the retail apocalypse when they cannot force studios back into traditional windows and cannot survive their mountains of debt." Theaters probably won't disappear entirely. But if the major chains collapse, far fewer screens will remain. And the survivors will likely be those that offer a premium experience for cinephiles, differentiated from today's generic cineplexes.

If movie theaters as we know them go the way of the dinosaur, that leaves big questions for moviemakers, questions that producers like Sonnier are already beginning to ponder. "As much as we'd like to say 'this will all be over soon,'" he says, "with projections being made for second and third waves of infection in this pandemic, we all have to be prepared to continue to release movies from home. If studios aren't prepared to make that decision on some of their biggest, most anticipated titles, what happens then?"

It's not that movie producers, large or small, would have to stop making films entirely. But they would have to build in different assumptions about how and where people will see them. That, in turn, would mean making different types of films.

One possibility is that this year's losses could foster studio consolidation, driving more production under the umbrella of a few big players, like Disney, which recently bought Fox and already nabbed more than 60 percent of total industry profits in 2019. But in May, Disney reported that its profits were down 91 percent in the previous quarter—before the pandemic took its biggest toll. So it's also possible the crisis could open up new opportunities for smaller-budget, smaller-scale productions that don't depend on outsized global box office returns—movies, in other words, of the sort that Cinestate specializes in.

Whatever happens, Sonnier believes the movie business won't emerge unscathed or unchanged. "I think that we've yet to witness the big, real changes that are going to happen here," he says.

The communal experience of watching movies in a pitch-black room with hundreds of strangers might never be common again. But even still, in the weeks after theaters went dark, people found ways to watch things together. New York Times film critics, who suddenly had no films to criticize, started a weekend "viewing party" in which readers were encouraged to watch movies like Top Gun and His Girl Friday over the weekend, with follow-up discussions with Times critics later in the week. In some parts of the country, old drive-in theaters staged a comeback, and restaurants converted parking lots into neo-drive-in experiences. Netflix Party, a web browser extension, allowed viewers in different locations to sync up their shows. The South by Southwest film festival, one of the first major events to shut down in response to the virus, was resurrected in the form of a 10-day online event on Amazon Prime Video. The American Film Institute, a nonprofit that runs several movie theaters, hosted a movie club, encouraging viewers to watch a slate of classic films and releasing short video introductions featuring famous actors and filmmakers. The tagline was "movies to watch together when we're apart."

Cinestate found its own ways to keep viewers engaged, hosting viewing events in partnership with the horror-film streaming service Shudder and transitioning a previously scheduled theatrical release to Vimeo On Demand, with part of the proceeds benefiting theaters. "We're certainly heartsick over the temporary loss of the theater-going experience," says Sonnier, "but we're finding ways to keep that spirit of community alive."

Alone, Together

By now you may have picked up on a theme: communities staying together by going online. Under lockdown, virtually all of what passed for social life shifted to the internet—to video game streaming services and video chats, to Twitter and Facebook, to YouTube and Netflix, and, perhaps more than anything else, to Zoom.

Zoom, an online videoconferencing service that launched in 2011, was the portal through which quarantined life continued. In the weeks after the lockdowns began, it became the go-to platform not only for workplace meetings but for after-work happy hours, birthday get-togethers, dinner parties, even church services. In mid-April, the state of New York legalized Zoom weddings. (Presumably kissing the bride was still done in person.)

Every videoconferencing service saw growth, but from December 2019 to March 2020, Zoom went from 10 million users to more than 200 million. In April, when the British government voted to continue operating by using the service, The Washington Post ran an article headlined "U.K. Parliament votes to continue democracy by Zoom." In the space of a few months, Zoom became an all-purpose platform for human connection and the functioning of society.

This was a modern blessing: Humans confined to their houses could talk to each other, see each other, smile and laugh in each other's virtual presences. Technology and human ingenuity had allowed us to preserve our social lives, our religious communities, our family gatherings and friendly outings. There was something heartening about watching people adapt to their new lives, carrying over their old habits and traditions, like immigrants from a previous time.

Yet as genuinely marvelous as the Zoomification of social life was, it was hard not to wonder: How much had really been salvaged? Yes, there was something reassuring in being able to communicate with other people, but in the course of retaining our connections, we'd transformed all of human existence into a conference call, with all of the frustrations those entail: shaky connections, bad lighting, poor audio quality, confusion about whose turn it is to speak, the inherent alienation of communication mediated through screens. This was, at best, a kind of social limbo, and sometimes it felt like something worse. Hell is other people on Zoom.

The online space we'd moved into was almost certainly better than the alternatives available to us, and it came with tangible benefits. But it was a substitute experience, a simulacrum of human connection, an ersatz social space standing in for the real thing. We'd cobbled together imperfect replicas of our old lives, cramped into tiny boxes on computer screens.

In my last days in the old country, the one I used to live in, I visited the Columbia Room with several friends. The Washington, D.C., establishment is known for its elaborate liquid concoctions; in 2017, it was named best cocktail bar in the country. We spent the better part of the evening there, sitting close together, unconcernedly breathing each other's air, and even sharing sips of drinks.

A bar like the Columbia Room isn't just a delivery system for cocktails. With its tufted leather seating and its intricately tiled backbar mural, its plant-walled patio and ink-colored cabinets full of obscure booze, it is also a particular space, designed for comfort and socializing, for being near other people and enjoying conversation and company. It has, in other words, a vibe. Roughly a month later, that place—and every place like it—was closed.

The Columbia Room continued to serve cocktails to go, a legal innovation intended to ease the burden of the lockdowns on businesses and imbibers alike, but it wasn't the same. It couldn't be.

Producing take-out cocktails is "very different from the bartending that you're used to," says owner Derek Brown. "The main difference is the ritual and engaging with the customer. There's a ritual to making a cocktail. There's an interaction to it." And with the Columbia Room closed to in-person business, that's gone. "We're very sad—sad is the only word—that we can't do that right now," Brown says.

That's what we lost to the coronavirus: not the cocktails themselves, but the ability to share them. Not competitive sports, but the companionship of playing games together. Not movies, but the experience of seeing stories on a big screen surrounded by friends and strangers. In the new country, we were suddenly, terribly alone.

Among the most upsetting aspects of the lockdowns, especially for those who live in dense cities, was the closure of many public parks and green spaces. Most beachgoing was prohibited. In New York, playgrounds were shuttered and parts of Central Park were cordoned off. As the orders went out, Gov. Andrew Cuomo complained about crowding in public spaces, warning that although people should try to "walk around, get some sun," there could be "no density, no basketball games, no close contact, no violation of social distancing, period, that's the rule." The message was clear: Stay away from each other.

In Washington, D.C., where I live, authorities blocked road access to the Tidal Basin in late March, as the city's famous cherry blossoms reached the peak of their annual bloom. The National Arboretum was closed, and the city parks department spent the month of April tweeting the hashtag #StayHomeDC; all the facilities the agency oversaw remained closed.

Officially, nature was more or less off-limits, just as spring arrived. Yet as the weather warmed, and the light lingered later and later into the evening, people emerged from their homes. The streets, mostly emptied of vehicle traffic, created space for runners, allowing them to leave the sidewalks for families and dog walkers. In my neighborhood, a small private park, nestled behind a block of houses and maintained by the community, became a place to stretch out and read a book under the sun.

Before the virus, I didn't go to the park very often. But in this new country, I found myself visiting more frequently, sometimes in the middle of the day. And so, I noticed, were my neighbors.

People sat in the grass and spread out picnics, walked their dogs, played catch with their kids. The park never became genuinely crowded, but it was always populated, a place where you could see other people and, at an appropriate distance, be reminded of their existence. Somehow, going to the park on a sunny afternoon had become an act of solidarity, of necessity, of rebellion. We were all alone in this strange time, this familiar yet deeply foreign place where the authorities had told everyone to stay apart. But at least we had found a way to be alone together.

Show Comments (31)