Roberts Accuses Kavanaugh of Judicial Activism in Coronavirus Church Closure Case

"Although California's guidelines place restrictions on places of worship," Roberts wrote, "those restrictions appear consistent with the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment."

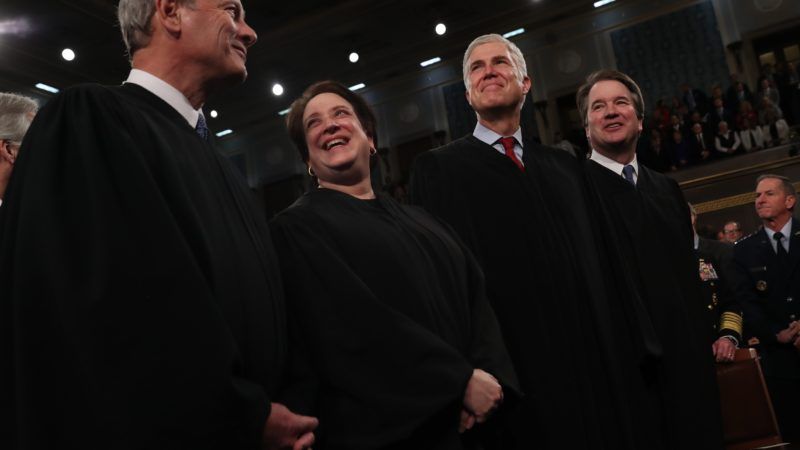

The constitutional showdown over coronavirus church restrictions has driven a deep wedge between Chief Justice John Roberts and his fellow Republican appointees on the Supreme Court.

On Friday the Court rejected a California church's efforts to block the enforcement of a state order that allows shopping malls and certain other businesses to reopen at 50 percent capacity while allowing churches to reopen at just 25 percent capacity. According to the South Bay United Pentecostal Church and its legal team, that differential state treatment violates the religious liberty secured by the First Amendment.

Four justices were prepared to take the church's side. According to the Supreme Court's order on application for injunctive relief in South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, "Justice Thomas, Justice Alito, Justice Gorsuch, and Justice Kavanaugh would grant the application."

Writing in dissent, Kavanaugh, joined by Thomas and Gorsuch, spelled out his reasoning. "California's latest safety guidelines discriminate against places of worship and in favor of comparable secular business," he declared. "California already trusts its residents and any number of businesses to adhere to proper social distancing and hygiene practices. The State cannot 'assume the worst when people go to worship but assume the best when people go to work or go about the rest of their daily lives in permitted social settings.'"

That dissent drew a sharp rebuke from the chief justice. "Although California's guidelines place restrictions on places of worship," Roberts wrote, "those restrictions appear consistent with the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment." According to Roberts, the state's treatment of churches is not actually dissimilar from its treatment of "comparable secular gatherings…where large groups of people gather in close proximity for extended periods of time," such as concerts and movie theaters. The state "exempts or treats more leniently only similar activities," he argued, "such as operating grocery stores, banks, and laundromats, in which people neither congregate in large groups nor remain in close proximity for extended periods."

Roberts then accused Kavanaugh and the other dissenters of judicial activism. "Our Constitution principally entrusts '[t]he safety and health of the people' to the politically accountable officials of the States 'to guard and protect,'" the chief justice wrote. And those politically accountable officials, he insisted, "should not be subject to second-guessing by an 'unelected federal judiciary,' which lacks the background, competence, and expertise to assess public health and is not accountable to the people."

This is not the first time the chief justice has accused his opponents of judicial activism in a hot button constitutional case. When Roberts led the Supreme Court in upholding Obamacare's individual mandate in 2012, for example, he justified his decision as an act of deference to the elected officials that brought the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act to life. "It is not our job," Roberts said in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, "to protect the people from the consequences of their political choices."

Roberts struck an equally deferential pose three years later when the Court recognized the constitutionality of gay marriage. Writing in dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges, the chief justice attacked the majority for second-guessing the wisdom of those democratically accountable lawmakers that prohibited same-sex unions. "Allowing unelected federal judges to select which unenumerated rights rank as 'fundamental'—and to strike down state laws on the basis of that determination—raises obvious concerns about the judicial role," Roberts declared.

The question of when and how the Supreme Court should act in constitutional cases is one of the most important debates in American law. The side that favors judicial deference clearly has a friend in John Roberts.

Related: "Coronavirus Cases Pit Constitutional Rights Against Public Health Authority."

Show Comments (224)