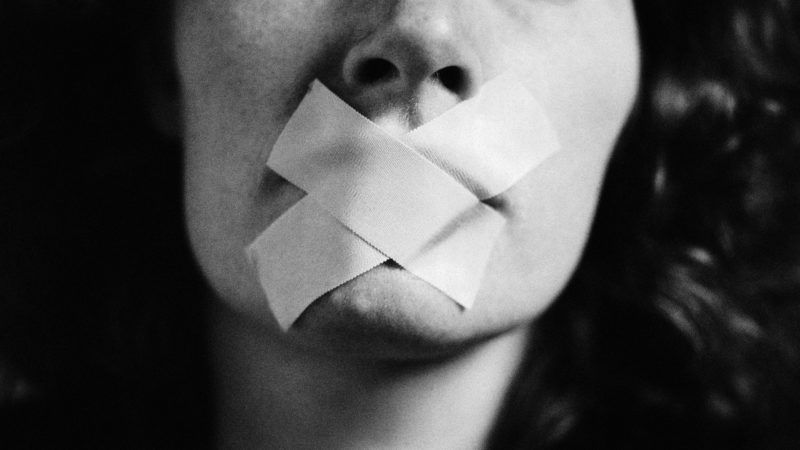

Supreme Court Can Put a Stop to Rule Compelling Anti-Prostitution Speech From Anti-HIV/AIDS Groups

The anti-prostitution pledge is unconstitutional when applied to U.S. nonprofits. But the feds say it's still OK to compel speech from these groups' foreign affiliates.

The U.S. Supreme Court may soon overturn a rule requiring groups that receive government grants for anti-HIV/AIDS work to publicly pledge opposition to prostitution.

Beginning in 2003, Congress said domestic and foreign nonprofits that get federal assistance to help "prevent, treat, or monitor HIV/AIDS" must have "a policy explicitly opposing prostitution and sex trafficking." The rule was passed as part of the U.S. Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act, which also stipulated that these groups would be ineligible for any new grants or programs created by the law if they "promote or advocate the legalization of prostitution or sex trafficking."

Nobody is advocating in favor of making sex trafficking—that is, commercial sex that's coerced or forced—legal. But prostitution between consenting adults is another matter. And from a public health perspective, criminalizing the latter makes no sense. Keeping consensual prostitution illegal only makes sex work more dangerous for everyone involved and makes practicing safe sex (and fighting sexually transmitted infections like HIV) more difficult.

Back in 2013, the Supreme Court said the pledge requirement was unconstitutional when applied to U.S. nonprofits because it violated these corporations' First Amendment rights.

But what about foreign affiliates of U.S.-based groups—is the anti-prostitution pledge clause applied to them still a First Amendment violation? That's what justices are now considering. On May 5, the Court heard oral arguments in United States Agency for International Development v. Alliance for Open Society International, Inc.

"After a little over an hour of argument by telephone, it seemed that the answer [to the First Amendment question] will probably still be yes," writes Amy Howe at SCOTUSblog. But "the vote may be closer than it was seven years ago."

Last time around, justices ruled 6-2 that making these groups take an anti-prostitution pledge as a condition of grant funding was unconstitutional (with Justices Clarence Thomas and Antonin Scalia dissenting). Justice Elena Kagan recused herself last time and will do so for the new case, too.

Arguing on behalf of the Alliance for Open Society International in Tuesday's teleconference session, David Bowker told the Court that U.S. groups suffer reputational damage when foreign affiliates sharing their names and missions appear to support prostitution criminalization. Yet partnerships with these foreign affiliates are often a necessary condition of carrying out work abroad, Bowker said.

Chief Justice John Roberts agreed that "it's undisputed that to be effective in many of the foreign countries involved here, you have to operate through a foreign entity."

Howe has more details:

What kind of ties, Chief Justice John Roberts asked, would the government require to attribute the speech of the foreign entity to the domestic one? [Assistant to the U.S. Solicitor General Christopher] Michel responded that when two groups have opted to be separate legal entities, they will have separate legal rights. They have to take "the bitter with the sweet."

Roberts did not seem entirely convinced. He pushed back, asking whether it is reasonable for the government to insist "on formal legal ties in this context," particularly if an NGO needs to operate through a foreign entity to be effective overseas. Especially when the domestic and foreign NGOS have "the same logo, the same brand," Roberts wondered "if it makes sense to think of foreign entity as another channel for domestic entity's speech."

Roberts pressed this point again later with Bowker, asking him whether the U.S.-based NGOs can control what their foreign affiliates say on the question of prostitution and sex trafficking.

Bowker responded that, "as a practical matter," the U.S.-based NGOs can indeed "veto" speech by their foreign affiliates on these issues.

Justice Neil Gorsuch also seemed somewhat unconvinced by the government's argument. It seems "to rely on legal separation," said Gorsuch. "But why does the First Amendment care?"

Past Supreme Court cases "seem to suggest" justices "are less concerned with corporate formalities" regarding business structure and more with public perception, suggested Justice Sonia Sotormayor.

Meanwhile, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg expressed skepticism that the imposition on anti-HIV/AIDS groups made sense when there was not a similar requirement for other public health groups, like the World Health Organization (which is in favor of decriminalizing prostitution) and Justice Stephen Breyer suggested the same arguments against the pledge that applied in 2013 were valid in this case as well.

Justice Thomas, who dissented from the majority last time, "did not necessarily seem to see much difference between today's case and that one" either, according to Howe.

And Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Samuel Alito expressed concern that striking down the anti-prostitution pledge would have ripple effects on other government rules. Kavanaugh's specific hypothetical: "Suppose the U.S. government wants to fund foreign NGOs that support peace in the Middle East but only if the NGOs explicitly recognize Israel as a legitimate state. Are you saying the U.S. can't impose that kind of speech restriction on foreign NGOs that are affiliated with U.S. organizations?"

Federal lawyer Michel encouraged a broad interpretation, suggesting that ruling in favor of the nonprofits here could somehow invalidate rules against foreign donations to election campaigns. But the anti-prostitution pledge, in this case, is "unique," responded plaintiffs' lawyer Bowker. Ruling it a First Amendment violation would be a "very narrow" decision, he told justices.

The Court is expected to issue a decision this summer. You can listen to Tuesday's oral arguments here.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

So the actual question is "Can foreign corporations claim rights under the constitution of the United States?"

Corporations can have rights, just not ones that engage in wrongthink.

Change Your Life Right Now! Work From Comfort Of Your Home And Receive Your First Paycheck Within A Week. No Experience Needed, No Boss Over Your Shoulder...wxz.. Say Goodbye To Your Old Job! Limited Number Of Spots Open...

Find out how HERE...... See More here

I wonder what the membership of the "Anti-HIV/AIDS groups" think about Chik-Fil-A being denied airport concession contracts because an owner has politically incorrect views on homosexuality?

It would seem to be at least an analogous situation.

I have to admit that I don't see how this is a First Amendment problem at all. I happen to agree that the anti-prostitution speech is bad policy and probably counter-productive. But if you don't want to deal with those restrictions, don't take the money. If you do want the free money, why is it a surprise that it comes with strings attached?

Since the War on Drugs has started to wane (after many decades of failure), it is time to ramp up the War on Sex, especially in non-monogamous forms including prostitution.

Most officials believe in their heart of hearts that they simply can’t allow individuals to exercise too much freedom over their personal choices or what they do with their bodies to feel pleasure (not to mention making some money). Free folk can get uppity.

Allowed too much liberty, officials fear some of those folks would start insisting on things that are unconscionable to them and their power, such as term-limits, an end to the two-party system, and (gasp) balanced budget amendments.

And this is why having the government fund things is incredibly dangerous.