States Can't Shut Down Non-Essential Businesses Without Harming Essential Ones

The coronavirus outbreak offers another view of the limits of central planning.

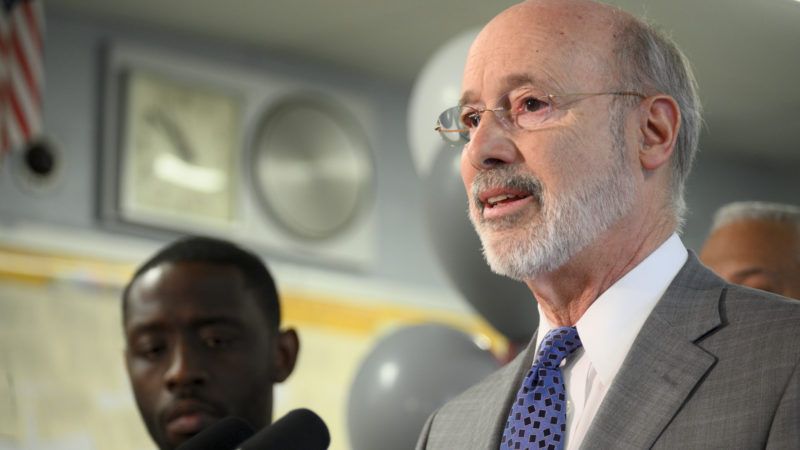

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf (D) issued one of the more sweeping responses to the COVID-19 outbreak on Thursday evening: he ordered all "non-life-preserving" businesses in the state to close, indefinitely.

"To protect the health and safety of all Pennsylvanians, we need to take more aggressive mitigation actions," Wolf said in a statement announcing the new anti-virus measures. "We need to act with the strength we use against any other severe threat. And, we need to act now before the illness spreads more widely."

Acting "with strength" meant threatening fines, citations, and the loss of licenses to any business who defied Wolf's order for more than a day—the order to close took effect at 8 p.m. on Thursday, but enforcement would be postponed until Saturday morning, the governor's statement explained.

By the end of the day on Friday, governors in California, Illinois, and New York had issued statewide orders to shutter so-called "non-essential" businesses and telling people to stay home except for emergency situations. But all those states have more reported coronavirus cases than Pennsylvania does, and none of those other orders came with similar promises of punitive measures.

Republican lawmakers in the state's General Assembly criticized Wolf for the timing of his announcement. It was made after the close of normal business hours on Thursday, potentially leaving many businesses and employees unsure about what to do on Friday morning.

"The ill-prepared actions, announced after normal business hours, are not only an economic blow to every worker in the state right now but will have ramifications long into the future," Republican legislative leaders wrote in a joint statement. "It is incumbent upon all state leaders to recognize that long after we have defeated this public health threat, we must have the ability to create economic opportunities for all Pennsylvanians."

Even in the short-term, shutting off all supposedly nonessential economic activity poses a risk. "Many of the industries listed as 'non-life-sustaining businesses' in the governor's order are in fact part of the supply chain for other businesses listed as being a 'life-sustaining' business," the Pennsylvania Chamber of Commerce pointed out in a statement. To businesses subject to the order, the governor's announcement seemed confusing and arbitrary.

That's the difficult balance that elected officials and bureaucrats now must try to strike. How extreme should shut-down and shelter-in-place orders be, and how long should they last?

"If everything we do saves just one life, I will be happy," New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) said Friday, as he announced a new round of restrictions on businesses and individuals.

Yes, containing the virus' spread and helping prevent the health care system from being overwhelmed must be the top priority, of course, but it cannot be absolute in the way that Cuomo described. As the Pennsylvania Chamber pointed out, hospitals can't stay open without supply chains, and health care workers—and lots of other people—may need access to other nonessential services to get by.

Wolf's decision to include laundromats in his initial shut-down order is a good example. Those are indeed essential for many Pennsylvanians who may not have the necessary equipment to wash and dry their clothes—to say nothing of the people who own or work at laundromats—but they are also semi-public spaces where lots of people are touching the same handles, dials, and buttons.

By Friday night, however, the Wolf administration had reconsidered parts of the order. Now, laundromats can remain open, along with law firms, coal mines, hotels, accountants, and businesses connected to the timber industry—all of which had initially been subject to the shut-down order. The governor also postponed enforcement of the shut down until Monday morning, and the state announced a waiver process to allow other businesses to request permission to remain open as well.

Does that strike the right balance between protecting the economy and public health? Well, we can hope.

Under the best of circumstances, policymakers suffer from what the philosopher and economist F.A. Hayek famously called "the knowledge problem." Only a price-driven market can solve the endless complex questions of what is needed where, and in what amounts. The coronavirus has crippled markets to some degree, but they are finding ways to respond. Too often, policymakers seem determined to prevent that.

That being said, I'm honestly not sure that there is a right answer to the question of how far policymakers should be willing to go in pursuit of stopping the spread of COVID-19. But it seems plausible that we're underestimating the economic damage that these statewide shutdowns will do.

"I am deeply concerned that the social, economic and public health consequences of this near total meltdown of normal life—schools and businesses closed, gatherings banned—will be long-lasting and calamitous, possibly graver than the direct toll of the virus itself," writes David L. Katz, former director* of the Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center and president of True Health Initiative, in The New York Times. "The path we are on may well lead to uncontained viral contagion and monumental collateral damage to our society and economy."

"We should be putting more weight on the economic and health damage that will be risked by extended business shutdowns," writes Chris Edwards, director of tax policy studies at the Cato Institute. "Governments are offering emergency business loans, but that won't compensate for the massive income loss imposed if this extends for more than a few weeks."

Again, look to Pennsylvania. The New York Times' Jonathan Martin reported on Thursday that more than 180,000 of the state's residents had applied for unemployment benefits in the previous few days. And that was before Wolf's mandatory shutdown order took effect. For comparison's sake, there were 210,000 unemployment applications nationwide a week ago. Goldman Sachs expects more than 2 million Americans to seek unemployment this week alone—and that's before the more aggressive measures now being taken by some states.

In a press conference on Friday, Wolf said the shutdown order was necessary to protect Pennsylvania's health care system from becoming overwhelmed. He said the announcement was made after consultation with the federal government—including the White House and the Department of Homeland Security. That raises the prospect of similar orders being issued in other states in the days to come.

If so, then the question turns to enforcement. As Reason editor-at-large Matt Welch pointed out this week, enforcement of curfews and full-fledged economic shutdowns will require pulling limited resources away from other, likely more crucial purposes. And as Reason senior editor Robby Soave wrote, there are limits to what people are willing to endure. Total shutdowns cannot be expected to last for weeks or months. An equilibrium will be found—either purposefully and orderly by official policy, or haphazardly when people simply can't take it anymore.

Wolf deserves credit for backing down a bit from his initial order, and for trying to find that equilibrium, though it may be impossible. The coming days and weeks will tell if he has succeeded.

There is little to do at this point but hope that our elected and appointed officials can pull the right levers and steer the country and its economy through this. But under the best of circumstances, we should be skeptical about their ability to do that—and these are far from the best of circumstances.

*This article originally misidentified David L. Katz's role at the Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center. He is the former director.

Show Comments (279)