Would a Presidential Pardon for Roger Stone Be Unconstitutional?

The argument requires several controversial assumptions and leaps of logic.

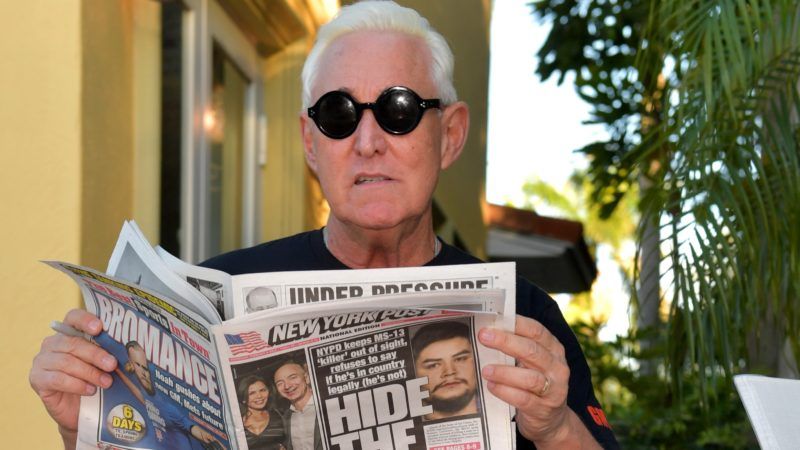

President Donald Trump has suggested he might pardon Roger Stone, a longtime crony who last week was sentenced to 40 months in federal prison for obstructing a congressional investigation, lying to a congressional committee, and tampering with a witness.

Not so fast, says Corey Brettschneider, a professor of political science at Brown University. Brettschneider argues that Trump does not have the power to save Stone from prison.

It's a bold claim, given the president's sweeping clemency powers under the Constitution. But Brettschneider notes that the "power to grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States" does not apply "in cases of impeachment." That exception, he argues in a Politico essay published today, rules out a pardon for Stone. It is hard to see how.

Brettschneider suggests that "cases of impeachment" include criminal cases against people who conspired with the president in the commission of "high crimes and misdemeanors" for which the president was impeached. Many legal scholars disagree.

During the Watergate investigation, New York Times reporter John Crewdson looked into the question of whether Richard Nixon could pardon himself to avoid criminal prosecution after he resigned or was removed from office. Based on his interviews with "constitutional experts," Crewdson flatly stated: "The exception [for 'cases of impeachment'] means that [the president] cannot restore the standing of a Federal officer who has been impeached and removed from his position; it does not mean that a President cannot pardon himself before his own impeachment."

After Bill Clinton was impeached, Slate considered the same issue and summarized the opinions of several experts. "The simplest interpretation," it said, "is that the president can pardon any federal criminal offense, including his own, but cannot pardon an impeachment. In other words, Clinton is free to immunize himself from criminal prosecution, but has no power over Congress."

If a president who has been impeached can avoid federal prosecution by pre-emptively pardoning himself, it seems clear that he also can pardon someone who was convicted of crimes related to that impeachment. But even assuming Brettschneider is right about that issue, there is another obvious problem with his argument: Stone's crimes had nothing to do with the abuse of power described in the articles of impeachment against Trump, which alleged that he sought to discredit a political rival by pressuring the Ukrainian government to announce an investigation of him.

Stone, by contrast, was convicted of lying to a congressional committee about his attempts to help elect Trump by contacting WikiLeaks, which had obtained emails that Russian hackers stole from the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton's campaign chairman. He was convicted of witness tampering because he persistently pressured one of his WikiLeaks intermediaries to refrain from contradicting those lies.

"It is true that the Stone investigation concerned Russian involvement in the election and that the House charges focused on the more recent Ukraine accusation," Brettschneider writes. "But the articles of impeachment focused on the accusation of 'abuse of power,' and it is that general high crime at play in Ukraine and elsewhere that links the impeachment and Stone."

That is quite a stretch. By Brettschneider's logic, any criminal case that arguably relates to a presidential abuse of power would count as a "case of impeachment," regardless of whether the president actually was impeached for that abuse of power.

Nor is it clear how Stone's crimes are even arguably related to crimes by Trump. There was nothing illegal about the actions Stone tried to conceal. Trying to assist the Trump campaign by seeking information about the purloined emails was not a crime, although it was potentially embarrassing for a president who has steadfastly denied that Russia helped him win the election. And Special Counsel Robert Mueller found no persuasive evidence that the Trump campaign illegally conspired with Russia in any way.

Trump has claimed many powers he does not actually have, including the power to "open up our libel laws," the power to punish TV stations that irk him by revoking their broadcast licenses, the power to unilaterally ban firearm accessories, and the power to build a border wall that Congress never approved. But the list of Trump's imaginary powers does not include the power to pardon Roger Stone.

Show Comments (101)