Is Farm-Free Food the Future?

The end of agriculture draws nigh.

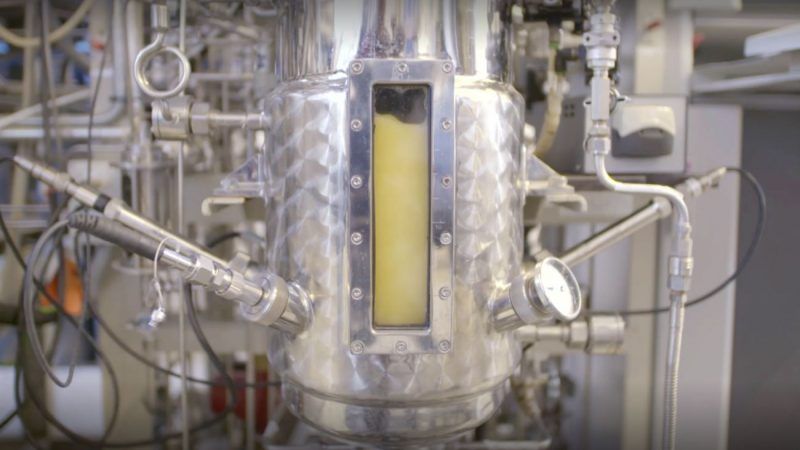

Factory farming may soon well mean something quite different than feedlot cattle and battery chickens. Entrepreneurs around the globe are seeking to replace conventional farming with shiny clean aluminum bioreactors that churn out tasty steaks, drumsticks, and flour. If this vision works out, the human footprint on the natural world will shrink dramatically since we use about one-third the world's land to produce food.

Recently, plant-based meats created by Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat have gained some traction in the marketplace. Both products have significantly less impact on the natural environment than does the equivalent beef product. For example, the carbon footprint of an Impossible Burger is "89 percent smaller than a burger made from a cow," according to one life-cycle analysis. It also "uses 87 percent less water than beef, uses 96 percent less land, and cuts water contamination by 92 percent." Another study found that a Beyond Beef burger "generates 90 percent less greenhouse gas emissions, requires 46 percent less energy, has >99 percent less impact on water scarcity and 93 percent less impact on land use than a 1⁄4 pound of U.S. beef." Of course, most of the ingredients for these products are still grown on farms.

Now comes the proposition that "ferming" in order to produce edible proteins and carbohydrates will displace most farming. Ferming is a portmanteau word combining fermenting with farming. "While arguments rage about plant-versus meat-based diets, new technologies will soon make them irrelevant," boldly asserts journalist George Monbiot over at The Guardian. Monbiot, who is promoting his new documentary Apocalypse Cow, explains that "before long, most of our food will come neither from animals nor plants, but from unicellular life."

Solar Foods in Finland functions as Monbiot's dawn herald of the brave new world of fermented foods. The company promotes itself as producing "food out of thin air." Solar Foods's fermenting microbes produce a high-protein powder, marketed as Solein, in bioreactors using carbon dioxide captured from the atmosphere and hydrogen generated using renewable electricity, along with added nutrients like sodium and potassium. Solein is 65 to 75 percent proteins and its amino acid composition is comparable to conventional sources like soybeans and beef. Consumers will not eat Solein flour directly. Instead, it will be a food ingredient replacing conventional proteins in almost any food product.

The company claims that fermenting one kilogram of Solein flour uses 500 times less water than producing a kilogram of beef and 100 times less than a kilogram of plant proteins. With respect to land use, Solein is 60 times more efficient than plants, and 1,000 times more so than beef. Taking post-farming afforestation into account (trees returning to abandoned cropland and pastures), producing Solein actually reduces atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations.

The company sunnily predicts that Solein will be cheaper than soy protein within five years. Prices vary, but one recent bulk wholesale price for soy powder is $600 for an order of 2 metric tons, or $3.33 per kilogram. Solar Foods' projection depends on, among other things, the continuing fall in the price of renewable electricity used to generate the hydrogen feedstock from electrolyzing water. The U.S. Department of Energy recently projected that commercial-scale solar PV power will drop from $0.11 now to $0.03 per kilowatt-hour by 2030. Electrolysis uses about 51 kilowatt-hours to generate a kilogram of hydrogen, implying a price of around $1.50 per kilogram. (Another analysis suggests that this hydrogen price milestone won't be achieved until after 2040.) Of course, any source of electricity could be used, but Solein's claimed climate benefits would thereby be significantly reduced.

Solar Foods is certainly not the only company aiming to end the age of agriculture by producing scalable food products that are generated rather than grown. Clara Foods, for example, is using sugar and yeast to produce egg proteins and Perfect Day Foods uses genetically enhanced microbes to ferment sugar to produce whey and casein to make animal-free dairy products. Israel-based Aleph Farms is producing slaughter-free steaks by using bioreactors to grow muscle, fat, and blood cells taken from cows.

The market for fish and seafood has not been neglected. Finless Foods is producing fish fillets and steaks by growing fish muscle cells in bioreactors, whereas Good Catch is pursuing the plant-based route to make fish-free tuna, crab cakes, and fish sticks. Unlike Solein, these companies use feedstocks still grown on farms, but nevertheless, the foods they produce use much less land, water, and fertilizer while generating far less greenhouse gases than do foods grown using conventional agriculture.

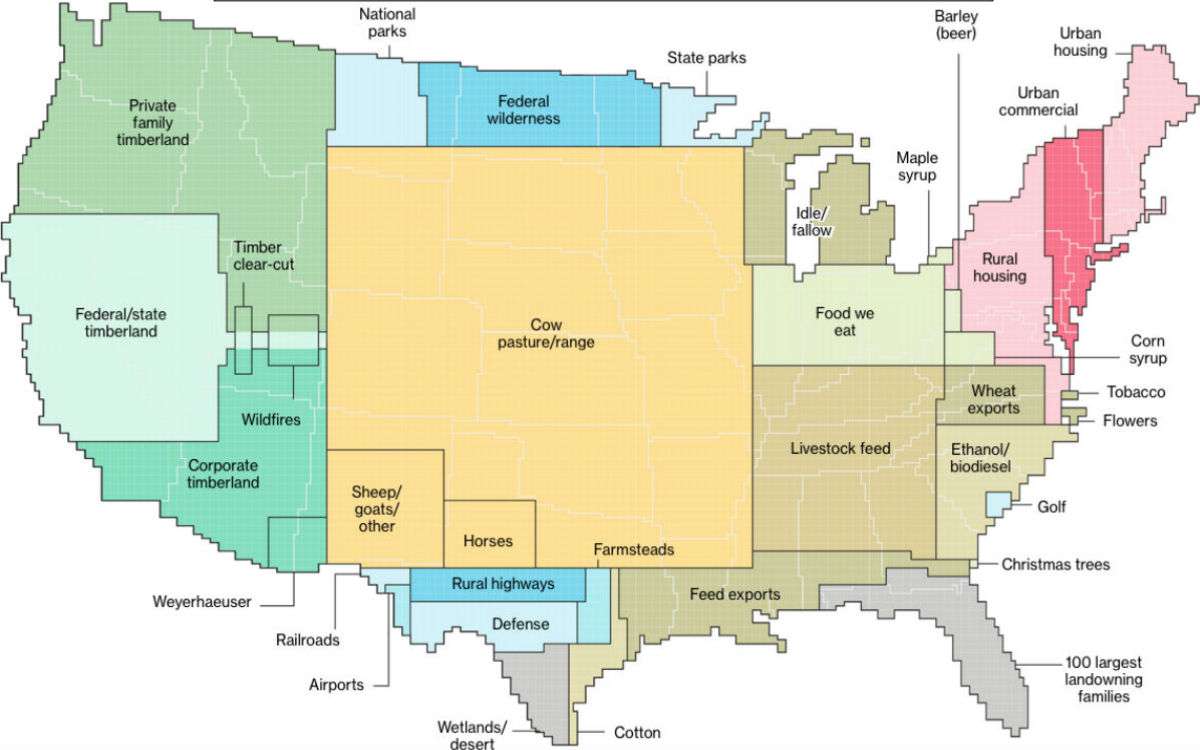

A 2018 study in Science calculated that meat, aquaculture, eggs, and dairy use about 83 percent of the world's farmland while providing only 37 percent of humanity's protein consumption and 18 percent of our calories. This map (below) from a fascinating Bloomberg News article on how we Americans use our land nicely illustrates just how much is devoted to agriculture in the United States.

Notionally speaking, if all meat, milk, egg, and fish production were replaced using generated rather than grown foods that could mean restoring 781 million acres devoted to livestock feed and pasturage to nature. That's about 41 percent of the total land area of the contiguous United States.

Is such a transformation really possible? Not only is this possible, but it is also likely and coming fast, assert the analysts at the independent RethinkX think tank. Their new report, "Rethinking Food and Agriculture 2020-2030,"contends that "we are on the cusp of the fastest, deepest, most consequential disruption of agriculture in history." RethinkX analysts predict nothing less than the collapse of industrial livestock production by 2030 due to being outcompeted by the development and deployment of precision fermentation.

"The cost of proteins will be five times cheaper by 2030 and 10 times cheaper by 2035 than existing animal proteins, before ultimately approaching the cost of sugar," states the report. "They will also be superior in every key attribute—more nutritious, healthier, better tasting, and more convenient, with almost unimaginable variety. This means that, by 2030, modern food products will be higher quality and cost less than half as much to produce as the animal-derived products they replace." They project that modern fermented foods will save the average U.S. family more than $1,200 a year in food costs.

To illustrate just how disruptive ferming will be, the report focuses on cattle production. The analysts project that precision fermentation will, by 2030, reduce the demand for cow products by 70 percent with similar declines for other livestock products. This fall in demand for conventional animal foodstuffs and products will have huge knock-on effects with respect to farm equipment, fertilizer use, livestock feed, and the value of farmland. For example, the demand for soy, corn, and alfalfa as livestock feed will decline by 50 percent by 2030. This disruption will free up hundreds of millions of acres that could be returned to nature while dramatically reducing water consumption, pollution from fertilizer run-off and greenhouse gas emissions. The RethinkX analysts project that the value of U.S. farmland will fall by 40 percent.

Given how conservative most folks tend to be when it comes to the foods they choose to eat, the RethinkX projections for a fast roll-out and adoption of fermented foods will perhaps turn out to be too optimistic. In addition, modern fermented foods will face some stiff headwinds, not least from incumbent farmers who will turn to politicians to help them fend off the competition; the usual claque of anti-technology activists; and, of course, over-cautious regulators.

Nevertheless, the prospect of much lower prices, better nutrition, and substantial environmental benefits all favor eventual consumer acceptance of foods made using precision fermentation.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

No, not the future. Farming is still where the overwhelming majority of our food is going to come from. I mean, duh. We going to make our food out of petroleum? Mine it? Nope, gonna grow it.

In any case, stop subsidies to farmers. Doesn't mean I'm against farming. It's still the cheapest and most eco-friendly way to get food.

I find your lack of argument unconvincing, but I agree we should end all subsidies.

You have to feed the microorganisms something. Where does that come from?

Apparently, the whole process is seen as like the Kilkenny cats. They lived off of eating each other.

So like progressives?

^LMAO..... PERfect....

Mystery growth medium from China?

Nice band name.

The question of where you get your input energy from is important. Is it more cost efficient to make silicon wafers to collect the suns energy or have your food grow its own solar collectors?

Well, if everything is based on photosynthesis, then why is "ferming" so much more efficient than regular plant farming? Now it's just a matter of efficiently collecting sunlight. You can do that with some weird vertical structure to take up less land, but you can do that with regular crops too. *shrug*

Now reference the EPAs estimate of agricultural contribution to GHG emissions (including livestock).

Also, your study about the amount of agricultural land is completely misleading. Beef cattle are raised on land unsuitable for crop raising. This is often arid land which requires huge tracts to support cattle growth. Plenty of research had demonstrated that grazing is actually beneficial for these grassland habitats. And just so you know, I have a MS in Animal Science, so yes I do know what I am talking about. Anybody with any range Management training would inform you that "returning this land to nature" would actually decrease the health of the land, unless you could magically restore bison and elk herds. The grasslands evolved with grazing and require grazing to maintain their health. If you eliminated cattle you would destroy the very thing you claim to be trying to help. Stop pushing scientifically unsound woo and get back to reporting on actual science. I once respected your science reporting. What happened to the guy who defended modern agriculture on Penn and Teller's show Bullshit? I guess you need those cocktail party invites more than scientific integrity.

Sorry that was meant for Ronald Bailey's post.

"What happened to the guy who defended modern agriculture on Penn and Teller’s show Bullshit?"

He joined the cult of AGW

Simpler handling, simpler harvesting, more controllable growth conditions, no pests, continuous industrial process, etc.

Now it’s just a matter of efficiently collecting sunlight. You can do that with some weird vertical structure to take up less land

Indeed. A cylindrical solar collector sounds great. You might call it Sol-indrical. I’m sure we could get funding for that.

Solar Foods uses CO2, air and electricity to make protein. That's why Ron says the cost of their protein is directly tied to power costs. In their case they have chosen to only use renewables. I'm sure someone else trying to do the same thing with cheaper sources.

Ok, yeah, you're not going to feed 7 B people with windmills and solar panels.

They have no intention of feeding 7 billion people. The ones they don't mass murder will die of attrition and mass starvation. That's literally what psychopathic climate change cultists likes Ron actually believe. The hilarious part is he very seriously believes he will not only live another century to see it come to fruition, but also will sufficiently ingratiate himself to the ruling class that his life will be spared despite his life having absolutely no utility.

Has he ever actually said that?

For his utopian "longevity escape velocity" claptrap see, for instance, "The Methuselah Manifesto" or "Eternal Youth for All!" among others. He tends to keep his genocidal fantasies barely-concealed under a sheen of transhumanist technoutopian bullshit about how declining fertility and Moore's law are going to obsolete most of the plebes.

This is correct.

Ok, yeah, you’re not going to feed 7 B people with windmills and solar panels.

Who said anybody was going to do that? Bailey didn't. I didn't either.

Algae live off atmospheric carbon dioxide and light. Yeasts live off sugars. Other microorganisms can live off electricity or chemical sources of energy.

Welcome to the world of blandness.

Ferming is a portmanteau word combining fermenting with farming.

So, after eating an "impossible burger" one ferts?

Fermenting I am familiar with. But I've never had farts bad enough where I was actually planting corn in the ground.

The impossible burger may be better for the environment, but it isn't better for you. Have you seen the nutrition info on those things?

"Ingesting as much oestrogen as a week's worth of birth control pills at a sitting has absolutely no health effects!"

I was talking about the calories, fat and sodium, not that debunked drivel.

Ahh, so you're a IFLS-regurgitating moron still bought into the lipid hypothesis and reassuring us that testosterone levels halving over the last 50 years is completely normal. Good to know.

HIGH testosterone levels are ABSOLUTELY ESSENTIAL when erecting war boners!!! Never-ending WAR will save us all!!! Get your war-boners on, one and all!!!

Ahh, so you like to make a lot of unsupported assumptions and pointlessly insult people so you can feel good about yourself. Good to know.

Hey Ron, How does the "ferming" process impact food allergies. Can they make a convincing substitute for crab meat or peanuts that won't trigger allergies in anyone? What about Celiac disease? Seems like they should be able to eliminate those issues and that would be a big selling point to a lot of people.

What about Celiac disease? Seems like they should be able to eliminate those issues and that would be a big selling point to a lot of people.

Why *actually* alleviate the symptoms of the disease when you can just pretend to eliminate the symptoms of the disease as a sales gimmick. Moreover, why pretend to just alleviate the symptoms of a very narrow and rare disease when you can manufacture a disease and then simply allege that you've alleviated the symptoms. Why, eventually you could regard whole biomes, cultures, and production systems as some sort of flawed disease and proffer your otherwise inferior product as *the* cure.

BS marketing gimics aside, my question still has value.

I like crab, but I'm allergic to it. My cousin actually does have Celiac disease. These problems aren't as common as they are made out to be by marketers and the media, but they do affect a lot of people.

BS marketing gimics aside, my question still has value.

Maybe if more accurately tailored or narrowly asked but, by your own precepts (or misinformation), you're asking if it can produce an invisible pink unicorn. Celiac disease isn't an allergy, isn't highly dependent on the method of preparation, and the allergy it's frequently confused with are even more rare than Celiac and also don't depend exceedingly heavily on preparation. Imitation crab is widely available now and plenty of people who are allergic to shellfish aren't allergic to it. Of course, you can find a significant portion of the population who doesn't have any known food allergy but will assert that they're allergic to imitation crab meat.

Will fake food cure fake diseases? Sure. Will fake food cure your real disease? No. It's just food that's fake.

I never said Celiac was an allergy. I put it in as a separate question for a reason.

"Fake diseases"? Are you saying that food allergies don't exist? And what is "fake food"? Is it something that looks like food, but is inedible? You're all over the place here trying to sound smart and informed, but you're just coming off like an opinionated ass more interested in pumping his ego than engaging in a meaningful conversation.

I put it in as a separate question for a reason.

OK, I was politely entertaining your idiocy (pretty directly there, right in the first sentence) but it's apparent that you want to play the role of stupid dipshit.

Celiac Disease isn't caused by meat or meat products. It's not exacerbated by them. In fact, at one point, meat based diets were the recommended treatment. The cause of Celiac Disease is well known and the treatment of food to avoid them is well understood and has abs-fucking-lutely nothing to do with fermentation. The vast majority of people claiming to have Celiac Disease and/or gluten sensitivity are parroting bunk science that the originating scientist himself has acknowledged is bunk. Similarly, many people can and do claim "subclinical allergies" and clinically unidentifiable sensitivities to substances that are hypoallergenic or to which no known human has been reported to be allergic.

Overarchingly, asking if fermentation will solve *either* your shellfish allergy or your Celiac Disease is like asking if a wrench will help you with your homework. If you happen to be learning about right angles or polygons a tire iron or combination wrench *might* be able to help you. If your shop teacher assigned you to take apart a car or your art teacher assigned drawing a still life a wrench will absolutely help you. For everything else a teacher could possibly assign you as homework a wrench is probably going to be between useless and irrelevant.

Are you saying that food allergies don’t exist?

Hurr durr, are you saying diseases can't be faked? Hurr durr.

And what is “fake food”? Is it something that looks like food, but is inedible? You’re all over the place here trying to sound smart and informed, but you’re just coming off like an opinionated ass more interested in pumping his ego than engaging in a meaningful conversation.

Hurr durr hurr why you use words like 'fake food' to sound so smrt? Hurr durr.

Whether your idiocy is feigned, learned, or genuine, I don't care. Go fuck yourself. Better yet, go fuck your cousin and report back on whether it cured your shellfish allergy and/or their Celiac Disease.

Meh. Soylent Green does all that and more.

Solein sounds like something you'd use to fatten Eloi.

Move over bacon...

Solein - can't believe the name. Maybe they'll dye the powder green too.

It's sure to provoke soyboy jokes too.

The company sunnily predicts that Solein will be cheaper than soy protein within five years.

By using only renewable energy?

*doubt*

I love that "cheaper than soy protein" is presented as a feature. Within the next 10 yrs. it will be cheaper than that inedible non-nutritive cardboard melamine slurry that was banned in China!

It the "taxes on the rich will pay for everything" version of this sort of wonder product.

I wouldn't invest in Solar Foods, but I might invest in a competitor that is using cheap power.

They should go to the plains states where they're flaring natural gas because they don't have enough pipe infrastructure to handle it all.

Although it seems a problem for the greenies if they're swapping out photosynthesis as their energy source, and using some other "renewable" energy source instead.

"Solar Foods' projection depends on, among other things, the continuing fall in the price of renewable electricity used to generate the hydrogen feedstock from electrolyzing water."

Do they ever give kilowatt hours per pound of protein?

I see lots of numbers, but not the one that counts.

Do these people understand how many types of food people eat in the world? Many types of meat , fowl, fish, veggies, fruits , ect. They can never replace all of that . Not to mention varying tastes.

They don't have to replace all of it. Replace low end beef, pork and chicken products and you've probably covered 95% of the meat that is eaten in the world. The rest can still be grown and processed the old fashioned way. The same goes for other categories of food.

Most arable land is used for crops. Rice, corn wheat, soy beans and others. Then you have vegetables , fruit and nut trees. Many countries eat large amount of fish and sea food. You Idea won't make a dent.

Replace low end beef, pork and chicken products and you’ve probably covered 95% of the meat that is eaten in the world.

I've long considered this to be the key to the abject failure of these products. It's somewhat akin to climate scientists who say we should be holding the climate in stasis and then getting on board jets or Elon Musk claiming to revolutionize the automotive industry and then practically refusing to deliver any car at a price point less than $45K or, and I know this one isn't very popular around here, the way crypto-currency users insist they'll replace credit.

There are foods, animal proteins, with massive consumer bases that are absolute garbage and have zero cultural relevance but they don't insist they could replace those. They insist they could replace beef, or filet mignons. Knock off fish sticks, then take down chicken nuggets, then we'll talk about replacing beef. When I see a BK commercial where people insist they can't tell the difference between a veggie whopper and a regular whopper I just assume that you could grind up a shoe and send it through the same flame broiling process, and these people would never know the difference.

"We're going to take over the world and you can tell by the way we abjectly fail to pick even the lowest of low-hanging fruit."

Ground beef is the beef version of chicken nuggets and fish sticks and that's the kind of beef they're going after first. The difference is that ground beef is more expensive per pound than chicken nuggets or fish sticks. They're literally doing exactly what you want them to do.

I don't see the cultured meat really displacing much of the market for even ground beef, until they manage to produce something closer to solid tissue. Right now the vat meat is more of a slurry than ground meat. And vegetarians will tell you the vegetable "beef" tastes like the real thing; How would they know?

But if they manage to break the solid tissue barrier, I could see it catching on. Especially if they can provide variety meats like elk or bison, and not just beef.

Personally, I've got a flock of chickens in my backyard, and am trying to transition away from having to buy meat in the grocery stores.

Especially if they can provide variety meats like elk or bison, and not just beef.

Think about what you're asking. Know anyone who can take something that's already a meat, like chicken, and effectively pass it off as elk? The vast majority of people with minimal development of their pallet and modest attention to detail can tell the difference between grass fed and grain fed beef. The turkey people have pretty decidedly acknowledged that turkey bacon is best meant to imitate bacon rather than supplant it.

The idea that people will be able to take soy or wheat or biofermented slurry and effectively replace whole cuts or even chunk pieces of meat is akin to the 3D printer people saying that in 10 yrs. we'll be printing off hand tools, metal and plastic, in your garage or the self-driving car people saying that in 10 yrs. nobody will own cars and parking garages will be a thing of the past. Not only is it bound to fail to meet all the expectations, nothing close to resembling everyone one wants it. They need to find their niche, like turkey, bacon and focus on that. Then, maybe, they'll be able to replace meat in places like taco bell tacos, italian meat sauce, and skyline chili. Even then, they should expect to cede ground to GM cows and other 'top-down' approaches that offer similar gains in efficiency.

Ground beef is the beef version of chicken nuggets and fish sticks and that’s the kind of beef they’re going after first.

It's almost like you paid absolutely zero attention to what I actually said and then said some things that you thought no one knew (but pretty much everyone over the age of 6 does) that you thought might, I dunno, help. The worst part is, you posted it a full day after I posted “We’re going to take over the world and you can tell by the way we abjectly fail to pick even the lowest of low-hanging fruit.” Pointing out that their reaching for the second or third highest fruit on the tree is just dumb.

Ever heard the statement "everything tastes like chicken"? Seems like it would be dead simple to put the chicken nugget industry out of business with a cheap substitute that tastes like chicken. Except they can't because chicken nuggets are dirt cheap and even 4 yr. olds can tell the difference between ground chicken, ground veggie byproducts, and chicken chunks. How about hearing someone offered a fully-processed and/or seasoned fish dish say "I don't like the taste of fish"? They're literally saying "If a textured substitute existed and you prepared it the same way, I'd eat it." Seems like if you could make a fish substitute people would effectively throw money at you. Except they can't because anything up to and kinda including garbage can substitute for fish and they can't make this stuff cheaper than garbage.

Even at restaurants known for serving effectively shit on a shingle cultural vegetarians and carnivores prefers their foods *based on their sources*. Nobody asks taco bell how much of their meat is actually derived from animal sources (it's predominantly beef and oats). It should be dead simple for vegetarians (who already patronize taco bell for their copious cheese, beans, and rice options) to completely subvert that meat source to an indistinguishable vegetarian equivalent *and they haven't/can't*.

Ahh, makes sense now. You're a vegan soy activist. LMAO.

I just had a bacon cheeseburger and chicken nuggets. What are you basing any of this on? Are you even reading what I'm typing before you respond? I'm just saying I'll happily buy a meat substitute if it has equal or better value than the real deal. And I suspect billions of other people will too.

And I suspect billions of other people will too.

There's plenty of evidence to suggest that you're wrong. As Asia and Africa have risen out of third world poverty, meat has displaced veggies and vegetable products in their diets. People who've spent several generations curdling and fermenting soy, soaking it in broth to make it taste like pork or beef are readily giving it up for the real thing and not because intrepid pork and beef producers have planned to reduce people's dependence on soy or because they believe meat to be more environmentally friendly, but because the customers want meat.

People may get rich by leading spartan lives, but they generally don't get rich in order to lead spartan lives. Mainly because you can lead a spartan life without being rich *and* because a spartan life is spartan.

The cow is sacred and the most wonderful animal that has ever lived, and if you try to keep me from eating it I will fucking murder you

Who's trying to keep you from eating it? Nobody in here is talking about outlawing beef.

Albeit both Warren and Yang have proposed taxing red meat to the point that the average American can't afford it.

Do these people care

understandhow many types of food people eat in the world?FTFY. And the answer is no.

And they shouldn't when replacing just a few of the most consumed food products with convincing substitutes will have a huge impact.

When they were trying to make a grain that produced beta-carotene there's a reason they started with rice instead of teff.

Fuck off you totalitarian piece of fear mongering shit.

Where is this coming from? What did I say that ever indicated I wanted to force anyone to do anything? Where did I ever try to scare anyone? I'm the most positive, optimistic person in this whole thread. You're projecting mightily.

Nevertheless, the prospect of much lower prices, better nutrition, and substantial environmental benefits all favor eventual consumer acceptance of foods made using precision fermentation.

Not if Greta Thunberg has anything to say about it. The idea that environmentalists will support this because they want what's good for the environment is nonsense - they don't love the environment, they just hate human beings. Food being cheaper and better for humans is the very worst thing about this as far as they're concerned.

Monbiot, who is promoting his new documentary Apocalypse Cow

The horror.

I am picturing cows with machine guns.

Doesn't quite carry the same gravitas when the natives parade out and then sacrifice a block of tofu.

There's also that scene where they're hurling hundreds of disposable straws at the boat.

I'm picturing The Cow from The New Adventures of Mighty Mouse.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pN69bPIv2yg

But Apocalypse Cow is pretty funny.

“I love the smell of cow dung in the morning!”

Apocalyse Cow is forty feet tall--and shoots fire from her teats!

Soylent Green. Nothing new here.

It's easy to see how Ron Bailey became a climate change cultist. When you can't comprehend at even the most rudimentary level something like agriculture it's probably very easy to be taken in my those fancy hockey stick graphs.

I can't even begin to tell you how gratifying it is that you will very soon be dying in a government-run hospital under the socialized medical system you champion, never to return from the void despite pissing away your inheritance on cryogenics in a futile attempt to preserve your completely, totally, and utterly useless life, Ron.

MH: FWIW, I may know a little bit about farming since I grew up on dairy farm. About 90 percent of the food I ate while growing up was raised my me and my family. Just saying.

And if you don't want to be transhumanist, that's certainly OK by me. Just leave us in peace.

MH: If you're interested, here's more detail about my farm background.

Are you trying to excuse your awful journalism with being a country hick? It's not working.

Try actually reporting science and not quoting advocacy groups, also, call out the misleading Bloomberg graphic. And report on the EPA's findings on GHG emissions and particularly agriculture's contribution. Also, report on modern range Management and the science behind it. Then we will be more willing to believe you are impartial rather then pushing a scientifically unsound point of view.

For your reference:

https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

BTW, I love some of the squares on the map. Christmas trees and maple syrup!

That big square in the middle represents sin. Sure, in actuality it represents ranchers grazing bovine on open land but, if fake meat takes off, we'd be able to purge ranchers of their sinful ways and return the land back to nature so that bovine can graze freely on it. Free from the tyranny of ranchers' evil machinations of property ownership and profit.

Nobody is saying that except you. What is wrong with replacing low end beef products (ground chuck, etc.) with a cheaper, imitation version? If you want to keep buying real porterhouses, the existence of this technology isn't going to stop you.

We are not herbivores.

That's a moral argument, not a logical argument.

No, it's an acknowledgment that Man's evolution into a thoughtful dominant species was largely driven by consumption of red meat and the protein it provided to brain development, as well as the reduction in jaw space to take up less cranial area

I don't understand what this has to do with anything I said. Personally I love meat. I just ate a bacon cheeseburger and some chicken nuggets for lunch. Meat trifecta.

Nobody is saying that except you. What is wrong with replacing low end beef products (ground chuck, etc.) with a cheaper, imitation version? If you want to keep buying real porterhouses, the existence of this technology isn’t going to stop you.

Nobody's saying you suck goat dicks and poison schoolchildren either, that doesn't mean you don't suck goat dicks and poison schoolchildren or that we shouldn't be discussing it.

Jesus Christ, it's a false dichotomy (or a series of them) dipshit. They're explicitly *not* saying it because they can't envision the narrative they're laying out or don't want the narrative to be seen that way. It's got everything to do with property rights and economics and nothing to do with fake meat vs. real meat.

You'd have to force the ranchers out of the business and off the land to make the pasture/ranch square disappear and even if you take the ranches out of the picture up there and the land doesn't disappear, it gets shuffled into the other bins. None of which are labeled 'Nature'. Idle/farrow is the closest you get and, even then it's not the most likely second choice.

There's also some considerable economic apples-to-oranges pasture/grass-fed beef vs. feedlot/grain-fed beef vs. cultured meat land/water/resource use comparisons going on. We could have more beef cheaper, but we don't because people like and we can afford the natural wide-open grasslands. Getting rid of the ranch/rancher in no way guarantees that the nearly natural wide-open grassland stays nearly natural.

Going further, it's not fake meat's fault if the ranchers' land gets turned into a federally mismanaged tinderbox as long as they're straightforwardly selling fake meat as a less intensive meat product. The issue I'm raising is that if they or their proponents are advertising their product as a means by which ranches get converted back to nature, they're doing something between lying and deceiving people.

Entrepreneurs around the globe are seeking to replace conventional farming with shiny clean aluminum bioreactors that churn out tasty steaks, drumsticks, and flour. If this vision works out

Anything within the next two generations is going to look a lot like a Tesla on autopilot.

Ag, that explains the new flame broiled whopper!

Smelting the aluminum alone will produce more CO2 than raising the cows does. Electricity will need to be dirt cheap to make this work. I don’t see it being widely adopted, although if they can make some high end products - read: pharmaceuticals - then there is a good case to be made.

Another study found that a Beyond Beef burger "generates 90 percent less greenhouse gas emissions, requires 46 percent less energy, has >99 percent less impact on water scarcity and 93 percent less impact on land use than a 1⁄4 pound of U.S. beef." Of course, most of the ingredients for these products are still grown on farms.

By the way, I don't believe any of these numbers.

Beyond Belief.

I'm sure the impact on land use and... water scarcity (WTF?) numbers are full explainable down to the nearest Newton-second.

By the way, I don’t believe any of these numbers.

Also, "When you start off with the assumption that carbon should be taxed and that humanity will run out of fresh water in the next 5 yrs., our product will be cheaper than soy in... 10 yrs.!"

Those pesky consumers better know whats good for them and make the right choices, right Ron? Otherwise they MUST be anti-technology activists.

This is a most evil of concepts. One of the main inputs is the earth destroying CO2!! To feed ourselves we would have to actually produce MORE of it!! RUN!!

Where is Greta when we need her? Is this one of her weeks to go to school?

The headline made me think, for a fraction of a second, that Reason had gone anarcho-primitive but as soon as I saw the byline I knew it was going to be some authoritarian, centrally planned, soylent greenish nightmare of government-mandated ersatz "substitute food".

Go reduce your carbon footprint in North Korea, Bailey

SIV: I guess you didn't notice that all of the companies mentioned in the article were privately owned? Curious.

No, Ron. He probably just noticed your usual condescending and self-righteous tone. You write as if you know what choices consumers ought to make.

Porsche and Hugo Boss were privately owned too.

I'd say this runs the risk of Godwinning the thread but Hitler managed to limit the scope of his insane hatred to Jews rather than all carbon-based lifeforms.

Think of how much someone must hate themselves to be a transhumanist.

It makes transgenders look well adjusted by comparison.

Some seriously deep mental disturbance going on.

Think of how much someone must hate themselves to be a transhumanist.

I don't have a problem with transhumanism/transhumanists. Aspiring to be something better than what you are is a big part of what makes humanity great. The problem is that few of these people are able to distinguish that (or consistently convey that they're able to make the distinction) from aspirations to make other people better than they are, which includes some pretty horrifying shit.

It's not the desire to be "better" that's the psychological issue, it's the rejection of one's biology and aspiration to replace it with machinery that reveals a deep disgust with one's own existence.

The basis of transhumanism as a philosophy is the idea that conscious thought is superior to natural evolution, which is fucking idiotic.

See the "downloadable consciousness" as an example, aspiring to completely eliminate the biological body's existence.

It's buddhism for people who can't control themselves enough to be a Buddhist, so they want to purchase nirvana

SIV is just worried that ferming will significantly reduce his dating pool.

FREE MARKETS

Ron, I'll reiterate a sentiment expressed on a board the other day; your willingness to wade into the figurative Mos Eisley that is the Reason comment section is much appreciated.

KMW should pay attention. If she wants clicks, this would be a way to get em. Have the ‘writers’ take turns on the comment section of their articles.

I'll reiterate my sentiments as well; I appreciate the effort but hope that he's wading into the forums of the whack jobs he's citing with equal vigor.

I guess you didn’t notice that all of the companies mentioned in the article were privately owned?

But how much government money has been used to develop these products? I’d bet more than half of the support has been government grants, particularly if you include the numerous failures that have disappeared.

Weird everyone getting so het up. If those companies can ferment a beef-substitute which is cheaper and I can't tell the difference, fine by me, probably good for humanity's environment too.

The only real problem I foresee is the damn greenies trying to mandate this stuff. You know they will try, and they won't wait til it's cheaper and indistinguishable from the real McCoy. The trouble they have now with guns won't compare to the trouble they get from fake beef.

Indeed! This is my fear as well. Just look at what happened to fur coats. Not outlawed, but canceled by the crazies.

Actually, California (naturally) has begun the process of banning fur coats.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/14/style/fur-ban-california.html

My issue is the misleading way he references advocacy groups and misleading graphics without the necessary disclaimer. See my above responses to his article, especially the bullshit graphic from Bloomberg.

I hate to be in the position of defending Reason, but they don't bother lying that they're "fair and balanced". They are an ideological activist publication. And yeah, it often quotes, uncritically, from advocacy groups without disclaimers. In almost all of their articles.

So quite simply, while your complaint is legitimate, it's not particular to this article or this topic. That's a complaint about Reason as a whole.

Ronald Bailey portrays himself as a serious science journalist. There is nothing scientifically sound about this article. Nor is there anything particularly libertarian about it either. If you study the funding of the companies, they are a collection of advocacy groups whose aim is to ban the eating of meat. Part of their goals is to create alternatives to meat, so that when they ban meat eating they will receive less pushback. Mr. Bailey should have referenced how that was the whole motive behind the inventor of the impossible burger. This is not a market alternative but the first step in a totalitarian push to control our diets on their religious beliefs (because environmentalism is a religion because it runs contrary to the science more often then naught).

Additionally, many of these groups want to ban the 0ublic from being able to visit the land that they are "saving".

If it were the Mormon church or Proud Boys or something else backing these projects, I doubt Ronald would have failed to mention that in his article.

The only real problem I foresee is the damn greenies trying to mandate this stuff.

Uh... the people making the stuff either are greenies or are in lock-step with them, quoting green philosophy as sales material.

Ask yourself this, why a beef substitute? Why not poultry? Why not fish? Why not egg or milk? Do America's beef farmers have aspirations of putting Dairy or Chicken farmers out of business? Do they quote the ecological superiority of beef over chicken? More tellingly, why would a fermented beef substitute mean we do away with pastures and ranching? Aren't people still going to own that property? Aren't undulates still going to roam those open plains? If not, why does fermented beef have a predilection to any sort of favorable outcome, isn't it just as likely that we replace all the ranches with federally mis-managed forests that catch fire and destroy whole communities?

I absolutely have no problem with an artificial fish stick, the real ones aren't very 'real' anyway. Milk's production costs and nutritional profile are pretty hard to beat and it's been massively displaced by Coke and tincture of almonds. These people nakedly expose their ambitions and it's exceedingly obvious that food production is merely a stepping stone. Whether it's by their own machinations or it's baked in to the green philosophy that makes up their precepts which, in turn, has red philosophy baked into it's precepts is not clear but is, depending on their actions, a bit moot.

Ron mentions a fish substitute in this very article. A quick internet search finds that Beyond Meat is working on a chicken substitute. Dairy alternatives already exist in droves, but more internet searching finds that people are still working on new solutions.

Yes. To make money selling by selling a product they think will make the world a better place.

Why is that a threat to you?

mad.casual and Michael Hunt are just irate over some argument that was made in some other article or in their own heads. The sooner they share what was said with the rest of us, the sooner we can have a meaningful conversation.

Except the science doesn't support that it will make the world a better place. Also, the funders behind these groups actually do support forcing people to become vegan. It is actually fairly well documented.

The only real problem I foresee is the damn greenies trying to mandate this stuff.

Don't worry, comrade! It will only be mandatory for the proles and the outer party members! They will be issued a nutritious fermented yeast paste and they will like it! It will 'taste', just like 'meat'.

We, in the Party, of course, need a more rigorous form of food, so that we may continue to work for the good of all, am I right, comrade? So we will take on the onerous chore of eating all the reactionary food we can--so that the proles don't have to.

It's for their own good.

What's that? You're not a member of the inner Party? Hey! can I get some muscle over here?!!

SLOEIN? Really? I am probably dating myself but does anybody remember the movie Soylent Green? It predicts a Malthusian future for the human race; overpopulation has overstressed the food-production capacity of the planet, resulting in desperation at all levels. Where they take the old, infirmed and useless in to make food for the masses!!!! Once all of the BOOMERS (me) have moooved along it will be an easier roll out! We enjoy a great steak, a nice single malt, and a good cigar way too much to eat baby food!!

Daniel Miller: What are you eating?

Bob Diamond: You wouldn't like this.

Daniel: What does it taste like?

Bob: You're curious, aren't you? I like that. Want to try?

Daniel: Yeah. Looks so weird ... Oh my God!

Bob: Like horseshit, huh? As you get smarter, you manipulate your senses. This tastes different to me than to you.

Daniel: This is what smart people eat?

-- Defending Your Life, 1991, Geffen Pictures

Great movie, highly underrated.

The impossible burger is soaked in au jus to get the meat flavor. Where do you think au jus comes from Ronald?

Also, Ronald, most pasture in the US was never forested, so very little will go back to trees. Grazed grass actually removes more CO2 then ungrazed grass. Fermentations main byproduct is CO2 and alcohol. What is the potential for scaling up. At a cellular level, yeast are more efficient but it takes a hell of a lot of yeast to produce a kG of protein, which requires a hell of a lot of sugar (what is the source of the sugar?). Come on you are supposed to understand science but are failing even basic chemistry and microbiology in this article.

Reaction to the article: Huh. My two main concerns are

(A) we've figured out that overly processed foods, as a group, tend to be unhealthy. We haven't quite figured out what "healthy" really means (see the variety in nutritional suggestions by country), but most of the stuff from the middle of the grocery store is going to lead to worse health outcomes then buying fresh from the perimeter. So I'm going to be skeptical, for a long time, that this stuff (whatever it ends up being) is actually healthier then fresh meat and produce. Our food industry just doesn't have a good track record here.

(B) You can talk up the benefits, but there are two real markets for this kind of food-replacement. At the high-end, you can talk it up as a moral/ethical thing, and (some) folks will buy/eat it even if it tastes horrible because they have the luxury of eating awful for moral reasons (see how the fancier the restaurant, the smaller the meal on your plate). The "Impossible" stuff did that first, where it was a fancy restaurant thing for years before it came to Burger King. At the low-end, you are just trying to make it the cheapest alternative available so that folks who are most motivated by price (rather then nutrition/ethics/etc) will gobble it up. The middle is the hard part, because that's where it has to beat out alternatives on price and taste. This is the real hurdle.

Reaction to the comment section: The overt hostility to trying something new is rather telling. This isn't government subsidized, this isn't being imposed. It's another option on the market. And there's a significant number of folks here who are taking a new option as a person attack. The fact that y'all sound like Bernie Sanders complaining that folks don't need that many deodorant options is lost on you.

Reaction to the reaction--

A) is pretty much spot on--and it's a wonder how stuff like this keeps coming to us from the same folks who decry overly processed foods.

It's almost as if they think they won't be having to eat it.

B) is also right there. The vast middle wants fresh, tasty choices--healthy is a plus, but not a demand. The edges are using food as penance or eating to keep the machine moving with as little cost as possible.

The Reaction to the reaction to the comments

Here's where you miss. It IS government subsidized and the people behind it are the type that like to impose.

That's what people are responding to.

Right now it's just another option.....supported by the Bernie fans that want us all put in gulags for wrongthink. Kinda makes you leery.

Then "people" are either ignorant or hypocrites.

To the degree this stuff is subsidized (and note how much of it is happening in other countries), the pre-existing American food industry is much more subsidized. So either "people" are ignorant, and think that the American food industry is standing on it's own two feet, or they're hypocrites because they're complaining about an upstart that's no where close to the level of government involvement that already supports the status quo.

You can be "leery" without being a fear-mongering nut-job.

Thank you both for an injection of sanity here. I was starting to think my browser failed to render part of the article. The part where Bailey calls for banning meat and fossil fuels while mandating hormone therapy.

Please show references to how much subsidies the US beef industry gets. Hint, it isn't that much compared to the rest of agriculture. And you are fucking kidding yourself if you think US farm subsidies come anywhere close to how heavily subsidized these companies are.

I do not think that we will get away from traditional foods or farming techniques for at least some time to come. There are strong tendencies on both sides of the political spectrum that each seem to favor farming and the rural lifestyle, albeit in slightly different ways.

On the conservative / right side, it's about tradition and values and hard work, rural cultural roots, etc. Family values. Guns, whatever. Conservationism and forest management - even some religious sentiment that it is not only our right but our duty to manage our natural resources by extracting value from them in a sustainable way, or even one that improves our environment. Stewardship.

On the progressive / left side you've got the anti-GMO nuts (party of science!), a strong proclivity toward anything labeled 'organic' and people who are sincere advocates of farm-to-table restaurants and grocers. They view food that is locally sourced as being better for the environment because less energy is consumed in its transportation, and better for the body because it's theoretically fresher when you eat it. In some cases, like locally produced honey, they believe it actually helps with allergies (it doesn't really work in any measurable way).

I don't see these people abandoning their preferences any time soon.

20 Years ago it was NutraSweet was going to kill of Table Sugar.

I predict it'll go exactly the way of NutraSweet (multi-choice) or the way of the other billion in a half Anti-Choice legislative wars.

If you're brainwashed by billions in propaganda (oh look the "studies"); you'll probably eat the NASTY stuff and be so upset about your own nasty propaganda-embedded habit that you'll go lobby government out of pure envy to make sure nobody can have anything they enjoy or desire anymore solely because you got duped by b.s.