A Survey Finds Speech Restrictions Are Pretty Popular. That's Why We Need the First Amendment.

Most respondents, especially millennials, favored viewpoint-based censorship, suppression of "hurtful or offensive" speech in certain contexts, and legal penalties for wayward news organizations.

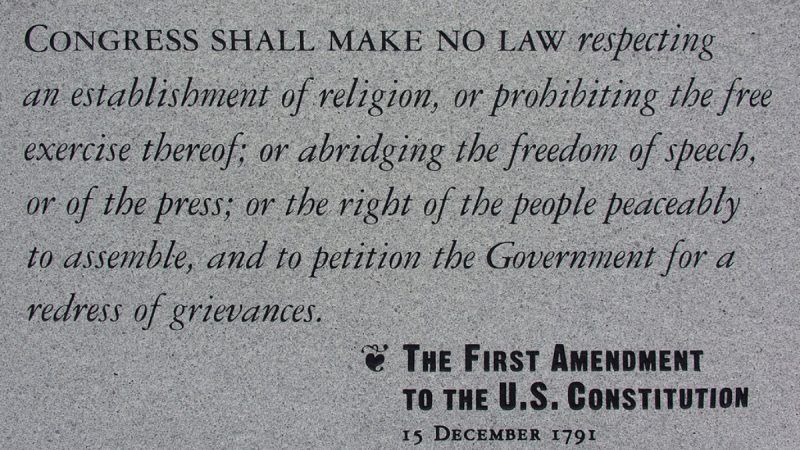

The First Amendment is unpopular…which is why we need the First Amendment. A recent survey commissioned by the Campaign for Free Speech underlines that point, finding that most Americans support viewpoint-based censorship, suppression of "hurtful or offensive" speech "in universities or on social media," government "action against newspapers and TV stations" that print or air "biased, inflammatory, or false" content, and revising the First Amendment, which "goes too far in allowing hate speech," to "reflect the cultural norms of today."

That last position was endorsed by just 51 percent of respondents, compared to 42 percent who disagreed and 7 percent who had no opinion. But 57 percent favored legal penalties for wayward news organizations, 61 percent supported censorship of "hurtful or offensive" speech in certain contexts, and 63 percent said the government should restrict the speech of racists, neo-Nazis, radical Islamists, Holocaust deniers, anti-vaccine activists, and/or climate change skeptics.

On a more heartening note, the idea of tasking "a government agency" with "reviewing" the output of "alternative media sources" mustered support from just 36 percent of respondents, although the opponents still fell short of a majority. Likewise with a law against "hate speech," which 48 percent favored and just 31 percent opposed.

"The findings are frankly extraordinary," Bob Lystad, executive director of the Campaign for Free Speech, told the Washington Free Beacon. "Our free speech rights and our free press rights have evolved well over 200 years, and people now seem to be rethinking them."

We have no data for prior years from this poll, which was conducted by CARAVAN Surveys in early September with a sample of about 1,000 adults. It is therefore hard to say, based on these results, whether Americans are actually "rethinking" their support for freedom of speech or simply expressing the qualms they've always had.

Survey data from the Freedom Forum Institute indicate that the share of Americans who think "the rights guaranteed in the First Amendment go too far" has fluctuated quite a bit since 1999. It was 29 percent in a survey conducted this year, which is higher than in the previous four years but far from a record during the last two decades.

Still, the breakdown of responses by age in the Campaign for Free Speech survey does not bode well for the future. On almost every question, millennials (ages 21 to 38) were more likely to support speech restrictions than older respondents were. But contrary to what you might think, people with college degrees were less inclined to favor speech restrictions than respondents who either did not attend or did not complete college.

If the rights guaranteed by the First Amendment were consistently supported by most Americans, of course, there would be little need to enshrine them in the Constitution. The whole point of a constitutional guarantee is to protect fundamental rights against the whims of passing majorities. While Lystad is right that a decisive turn in public opinion against freedom of speech and the press could jeopardize these liberties in the long term, it's not clear we are experiencing such a shift.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

So over half the country agrees with me that democrats should be silenced?

Cool.

Yes, it appears that the majority would agree that if Trump finds some speech offensive, then they would have no problem with his armed agents shutting it down. What's that? Oh, I see, speech banning only goes into effect when a D wins the presidency.

That is actually rather a small number, because I think it's fair to wager that far more than the majority agrees with the position we have been defending here at NYU for well over a decade: namely, that inappropriate "parody" that offensively impinges on the reputation of our faculty and institution should be immediately silenced and, where necessary, punished by prosecution, jail and any other available means. See the documentation of our efforts in this regard at:

https://raphaelgolbtrial.wordpress.com/

+1000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Awesome! I am totally going to flip that on Lefties who want to curtail free speech and free press.

Reporters have no interest in getting first-hand information about the "impeachment inquiry." Reporters are perfectly happy being spoonfed cherrypicked info from Schiff--secret testimony in which democrats call witnesses and selectively leak to the media. This isn't news, it's spin and political narrative controlled by Schiff. And the media is happy to be shut out and amplify this narrative.

The media were ready to go to the mat over Jim Acosta being shut out of the white house press room. But being shut out from an impeachment inquiry? Crickets.

Just because you don't like what Schiff is finding out about the Peach Peril doesn't mean its not true. The Senate will decide that. Don't worry the Turtle is still on your side. for now.

Yes, the all knowing Senate with their infinite wisdom is the one to decide truth.

More foolish than wise.

Sure, first they'll come for democrats and jail them, and next they'll comb through Reason.com comments and then come for you and send you to prison as well. That's how these draconian zealots think. See you in prison, bro.

I already had some SJW try to get me fired over a blog comment. HR came by on a Friday afternoon with a copy of their email, to assure me that they don't fire people over their politics.

But the idiot tried. Using a burner account, of course...

Yikes, what a piece of crap. You ever find out who it was?

Like I said, burner account. Asshole probably creates a new account on a weekly basis, and doxes people for a hobby.

Probably a smart decision, that burner account. I'm pretty mellow, but some people would burn your house down over something like that, if they could find out where you live.

Democratic supporters have already been silenced.

Conservatives can spew their lies in order to get the sheeple to support the murder of Americans at the hands of Conservatives vile evil murderous pro-pollution ideology:

https://news.vice.com/en_us/article/kzmy79/trumps-epa-knows-its-new-coal-rule-could-kill-1400-people-per-year

Trump’s EPA Knows Its New Coal Rule Could Kill 1,400 People Per Year

Yet I am not allowed to yell "FIRE!" in a crowded theatre in order to get a better seat, or call in a bomb threat if I'm running late for a doctor's appointment to hide the fact that I'm running late.

"Our free speech rights and our free press rights have evolved well over 200 years, and people now seem to be

rethinking themshitting all over them."FTFY

This clamor to put people in prison for offending, um, someone will not end well.

dear lord. stupid people need the most attention.

I can't believe they spelled "Congrefs" wrong in the 1A.

often we find things similarly amusing.

See? People were stupid back then. We know better now what the Bill of Rights really means.

"63 percent said the government should restrict the speech of racists, neo-Nazis ..."

I think we Koch / Reason libertarians should support this. Because we prioritize #ImmigrationAboveAll. We could define all opposition to our open borders agenda as racist and demand the government prosecute those who advocate hateful policies like "border enforcement." As Shikha Dalmia has noted, enforcing a national border is morally comparable to enforcing fugitive slave laws.

Good thinking, OBL.

We should silence all criticism that runs counter to the socialist ideals if we are to obtain a more perfect union of totalitarianism, terror, mass murder and a failed economy just like those lucky bastards in the People's Republic of China enjoy every day.

Keep up the good work, OBL.

You're comments are an inspiration to every closet totalitarian everywhere.

Hey OBL, I do wish you would quit cloaking yourself in the mantle of the prototypical "Koch/Reason Libertarians". That is very much what I am, but I find myself in frequent disagreement with you, or at least your tone. Thing one about being a libertarian is humility when telling others what to think, or how to act.

Lighten up dude!

"but I find myself in frequent disagreement with you, or at least your tone. Thing one about being a libertarian is humility when telling others what to think, or how to act."

"Lighten up dude!"

Hahahahahahaha

I’d prioritize bashing my skull into a fucking wall if I had to live with an arrogant prick like you, Trumpian suckup.

You suck at this.

And going by AOC questions to Zuckerberg, for example, racists and Neo-Nazis include center-right news organizations like the Daily Caller. Where they draw their lines as to what is unacceptable will include a lot of what are mainstream voices.

One of the many ways that democracy produces suboptimal outcomes.

My bet is that once the next war starts all these free speech conservatives will go back to calling people like me traitors. That’s what happened last time. It’s funny... free speech is a pretty good thing until advocacy for it runs up against US foreign policy establishment or some oil company’s interests.

The "US Foreign Policy Establishment" is wholly progressive regardless of which side of center their most vocal boosters are.

Just terrible at commenting. Should give up at this point.

Aren’t they already calling you traitors? You like Trump after all.

Now ask them if they support restrictions in freedom of speech if the other side is in charge and making the decisions.

Why would they care? It wouldn't make any sense to make restrictions on speech about homosexuality or transgenderism. Same with talk about punching nazis. Why would you restrict positive speech?

That's how they think. As a result, restricting speech they don't like is a no-brainer to them.

The only saving grace is that they all disagree on what speech is hateful.

You shouldn't be allowed to say that.

be easier if they'd hate each other

What is Reason's view of libel laws ?

Do they violate the 1st amendment ?

Tangible damage has to be inflicted for it to be libel. It's not a 1A issue.

Libel is a dispute between two private parties where one party alleged another party has caused them damage.

So its not really a 1st amendment problem.

No government involved, except as a court doing what it does for other sorts of private disputes.

No different than my neighbor felling a tree that lands on my house and refusing to pay.

According to the commentariat libel laws are not applicable except when it comes from a reporter from the NYTimes/CNN/MSNBC/Mother Jones/Pacifica/Jacobin/FAIR/Media Matters or Pornhub and says something that makes Dear Leader/any current Republican in Congress/Mitch McConnell’s wife/Ben Shapiro/Any CPAC participant since 2008 uncomfortable/angry or in any way impugns that any statement made by above person since 1851 might be racially motivated and in which might cynically or otherwise uncynically appeal to racists/crackpots/idiots or associated fuck-ups. Otherwise libel laws are completely unenforceable and null and void. Is that a fair characterization Reason crackpots?

You

Are

Full

Of

Shit

And a liar besides

Finally!

The masses are finally seeing the light of suppression the poison that is called free speech.

We are all too stupid to think for ourselves, and if it weren't for our obvious betters busy micromanaging our meaningless lives, we would all wander in the desert called freedom. Culling speech is the first, and perhaps the most important, step to establishing a socialist utopia those lucky bastards in Cuba, North Korea, Zimbabwe enjoy on a daily basis.

So let's all cut ties with this foul disease-ridden vermin called free speech and let our enlightened betters to our talking for us by enslaving us, throwing us into gulags, and indoctrinate in the prudent ways of socialism and its logical conclusion, totalitarianism.

Public school indoctrination works.

Average humans aren't very smart and are easily manipulated. The problem is the evil smart people will do literally anything for power. The good smart people won't. It's a definite handicap.

Also, demographic change.

Most respondents, especially millennials, favored viewpoint-based censorship, suppression of "hurtful or offensive" speech in certain contexts, and legal penalties for wayward news organizations.

Luckily the Tumber kidz won't have any effect on the larger culture going forward.

"Lystad". Ever since I read those vampire books years (decades?) ago, every time I see a name that starts with "L", I subconsciously put "the vampire" in front of it. "The vampire Lastat", "The vampire Lystad".

I believe the correct response to the anti-free speech crowd is "Fuck Censorship".

I'm more inclined to "do you feel lucky punk, well do ya?"

For 1st Amendment & punk discussions, I prefer the Dead Kennedys.

It is fun, though, watching Smiths/Morrissey fans lose their minds over his recent conservative gend. Don't worry emaciated vegetarian, he'll still be cancelling plenty of concerts.

I agree.

"...and legal penalties for wayward news organizations."

NYT hardest hit.

Reason hates the idea of being responsible for defamation and slander, but other than that they adore censorship.

Once again Reason follows the crowd.

Speaking of free speech Trump has not threatened to sue or jail a reporter in 58 days, 8 hrs, 33 minutes and... 45 seconds.Mark! Wow!

http://www.trump-clock.com/

Speaking of fucking lefty ignoramuses, you post here.

Just terrible.

Sue and jail are two very different things.

"So you're willing to go to prison if it is decided by others that what you have said should not be legally permissible?"

Well as long as the censor is an oligopoly of less than 10 media and publishing companies then there's no problem and any attempt to oppose the censorship is reactionary neo-Nazism, according to Reason. So who gives a fuck right?

You have no right to someone else's printing press

Exactly! You are to dutifully enjoy your censorship when it is imposed by the glorious invisible hand of the free market. Those half dozen multi billion dollar international corporations obtained their market position completely legitimately in a pure meritocracy. If you have a problem with natural and beneficial oligopolies that arise purely out of economic efficiency then you should just keep it to yourself. You have the right to petition the government for a redress of grievances, not to pester the government with annoying complaints about the market power of a private company operating in a true and veritable free market. The impudence of these neo-Nazis is truly breathtaking, isn't it?

So what's your plan? Nationalize Google?

Seems like the people who bitch the most about Big Tech are rather short on potential "solutions" that won't make things worse.

Yeah, because it's impossible to find any alternative, dissenting views on the internet.

That's a nice solar centric model of the planets you got there. It would be a shame to imprison you if you show it to anyone.

re: denying First Amendment rights to so called climate deniers.

"A Survey Finds Speech Restrictions Are Pretty Popular."

Jacob Sullum, meet Nick Gillespie:

"According to The Washington Post, Jarred Karal and Ryan Mucaj are also facing possible expulsion from UConn for violating the school's code of conduct. That's exactly right: The university should be deciding whether such mindless, ugly action warrants suspension of expulsion. Even though UConn is a state school (and thus bound by the First Amendment), it should be allowed to set reasonable expectations for student and faculty behavior."

From the pages of...Reason, three days ago.

Yikes.

Now do the survey results by race. And national origin. (While we are still allowed to say this). I'm curious who's all for free speech and who's against it.

I know, right? Why, everyone knows one's political opinions are determined by skin color.

In a large part, a person's outlook on life is shaped by one's culture.

"Hate speech is an act of violence."

46% of whites agreed.

75% of blacks agreed.

72% of Hispanics agreed.

"People who don't respect others don't deserve the right of free speech."

36% of whites agreed.

59% of blacks agreed.

62% of Hispanics agreed.

You cannot deny there are large cultural differences in how free speech is viewed.

Source: Free Speech and Tolerance Survey, Cato Institute, 2017

If you need a good What does Packaging Design cost? . Good news.

There's another element to this, however. If enough people decide they don't like the First Amendment for long enough, eventually they will get seats on the Supreme Court and start creating exceptions. (Hillary specifically campaigned on appointing people who would weaken it in regards to campaign finance.) So it's still important to educate people on why we need it.

"" eventually they will get seats on the Supreme Court and start creating exceptions""

First amendment, meet the second amendment.

I'd believe that Conservatives were sincere their support of lying/fraud being free speech if they were also advocating that Bernie, the Conservative media of investing, Madoff be set free because he merely gave people his opinion that they would get their money back if they invested it with him.

If Conservatives are allowed to spew their lies, then I should be able to yell "FIRE!" in a crowded theatre in order to get a better seat, or call in a bomb threat if I'm running late for a doctor's appointment to hide the fact that I'm running late.

Baaaaaaaaaaa!

The First Amendment is unpopular…which is why we need the First Amendment.

Huh. So liberty shouldn't be conditioned on what "the people want". I guess that's what those elitist Reason writers think, thumbing their noses at the 'real Muricans' in the heartland while sipping champagne at their Georgetown cocktail parties.

Swing and a miss, Jeff.

""So liberty shouldn’t be conditioned on what “the people want”.""

Not if what they want is the opposite of liberty.

The purpose of enshrining something into a right is to remove the concept that the 51% can deny it from the 49%.

Is your life subject to a vote?

Nobody’s had to fight for their lives for justice watching their friends die.

Uber pizza is the priority.

What a bunch of cunts. Whoops, I meant pussies.