Mad Magazine Is Dead

The comic magazine's ability to rib culture, politics, and business shaped the boomer mentality, and we should be grateful.

The comics community is abuzz with the news that Mad magazine will, after two more issues, cease publication of original material and abandon newsstand distribution, becoming a reprint title available only in comic book shops (with the exception, Hollywood Reporter reports, of one special issue a year of new content).

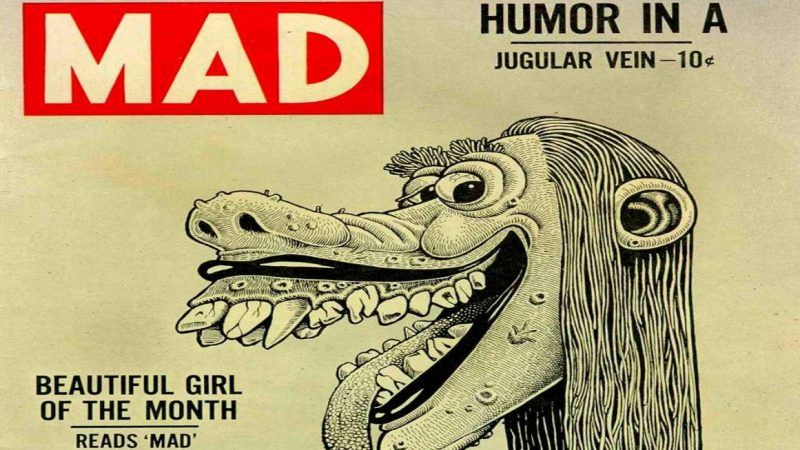

Mad began life as a comic book in 1952, the brainchild of then-obscure New York cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman, published by William Gaines' E.C. Comics. Through his work in Mad's formative years and at later humor magazines he launched—Trump (published by Kurtzman superfan Hugh Hefner, and not related to Donald), Humbug, and Help!—Kurtzman became a culture god to a generation of baby boomers who eagerly lapped up a brilliant, acrid, prickly adult with a fresh, warbly-wicked cartooning style to solidify and reify their inchoate sense that aspects of adult American culture were more absurd, more ersatz, sometimes even reprehensible, than their parents, schools, churches, or leaders wanted them to know.

Mad's influence on baby boomer humor and general sense of life is one of those cultural truisms that now sounds like a dull cliche that some Mad-level parodist should josh. But Richard Corliss of Time was not wrong when he wrote that Kurtzman "virtually invented what would become the era's dominant tone of irreverant self-reference," nor was The New Yorker's Adam Gopnik when he wrote that "Almost all American satire today follows a formula that Harvey Kurtzman thought up." (Both quotes from Bill Schelly's indispensable 2015 Kurtzman biography, Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Invented Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America.)

In a Reason feature in May, I wrote about how everything anyone loves about the modern explosion of adult, intelligent arty, self-expressive comics has direct lineage from the work in the 1960s–'80s of Robert Crumb and his cohorts in the first wave of American underground comix. Since the article was not a detailed history of influence in comics history, it did not step back to discuss the ur-influence that lay behind Crumb and other underground comix artists around him, which was Mad magazine.

Art Spiegelman was blown away by Crumb, and through his Pulitizer Prize-winning Maus and his tireless cheerleading for comics in mainstream publishing, museums, and culture is a linchpin of modern art comics. He spoke for himself, Crumb, and nearly all the first-wave underground comix maniacs when he said that "Seeing Harvey Kurtzman's work when I was a kid was what made me want to be a cartoonist in the first place. Harvey Kurtzman has been the single most significant influence on a couple of generations of comics artists." (And not just comics artists on paper—Monty Python's Terry Gilliam's formative job as a young man was as Kurtzman's assistant on Help! in the early 1960s.)

As Bill Griffith, underground comix creator of Zippy the Pinhead and partner with Spiegelman in editing the mid-'70s underground comix magazine Arcade, put it, "Mad was a life raft in a place like Levittown, where all around you were the things that Mad was skewering and making fun of…Mad wasn't just a magazine to me. It was more like a way to escape. Like a sign, 'This Way Out.' That had a tremendous effect on me."

For those of us who grew up in the world Mad made, it's bracing and peculiar to read Crumb and his epigones discuss the explosion of consciousness it caused in them to see the structures, mores, entertainment, and business of the adult world burlesqued, warped, questioned, and mocked. That wasn't normal then. Thanks to Mad, it is.

Everyone doing interesting work in comics, even if they never had a childhood dalliance with Mad, should aim a joyous and respectful Don Martin-esque PHLBTTTT!! in the direction of Kurtzman and all the usual gang of idiots who occupied the pages of the magazine he created for the past 67 years.

To its very first wave of fans, the golden age of Mad was short. When the comics code and the wave of anti-comics fervor of the mid-1950s drove E.C. out of the comics business per se, it shifted its bestseller Mad with its 24th issue to the magazine format it retained ever since. (E.C. ran ads puckishly playing on regnant McCarthyism and suggesting that the people most likely to want to censor comics were likely Communists.)

Gaines sold E.C. in 1961 and a few sales and mergers later it became part of the Warner Bros. empire, more recently officially part of Warner's D.C. Comics. Kurtzman, aware the magazine's comedy DNA was his own, had in 1956 asked publisher Gaines to cede 51 percent ownership of the magazine to him. Gaines refused, and Kurtzman walked. It remains one of comic fandom's cautionary tales of business exploiting art that Gaines pushed out the genius who created Mad and continued to profit from the reputation and style Kurtzman created.

Still, even generations who missed Kurtzman's era in real time continued to have their minds blown and sensibilities tickled by iconic artists and writers such as Al Jaffee, Wally Wood, Dave Berg, Don Martin, Mort Drucker, Sergio Aragones, and Jack Davis who kept the magazine going under successor editor Al Feldstein, who guided it through the late Boomer and early Gen X eras until 1984. Until 2001, Mad carried no paid advertising in an implied promise to its readers that no other considerations came between them and telling the sordid and/or ridiculous truth about the world they were growing up in.

If you were ever a fan, your golden age was usually the first year or so you read it, likely between the ages of 10–13. Mad was diligent about regurgitating its legacy in reprint special issues and paperback books, so if you wanted to check out its past you could. I've been re-reading a lot of old Mad myself lately, and while one cannot say that it "holds up" to an aging mind in 2019—it's more a magazine to absorb and leave behind in adolescence than a lifelong companion—it still manages to provide both interesting insights into old culture and the occasional laugh.

The focus in late '50s issues on such parody subjects as barbeques, weights and measures, box cameras, and fake backdrops to add versimilitude to adult fibs shows a magazine that wanted to elevate the cultural and behavioral sightlines of youngsters who might be reading it. Mad was the youth league version of the same boomer humor that adults were seeing in nightclubs with Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce and on TV with Ernie Kovacs and set the stage for National Lampoon, Saturday Night Live, and everything that follows them.

However Mad old or new reads to me now, I can't forget how, when I finally saw Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece Barry Lyndon on the big screen a couple of years back, I was seeing every frame through the jokes, references, and look of the Mort Drucker–drawn parody in the first issue of Mad I convinced mom to toss in the cart at the supermarket, where it appeared as—what else?—Borey Lyndon. Mad's goofy jokes have been many generation's deeply embedded truths about culture, politics, and business, and that has been a wonderful thing.

The magazine relaunched last year with a new issue number one and the offices relocated from New York to Burbank with a whole new staff, but the new version apparently didn't catch enough fire with paying readers to keep going.

Freighting it with nothing but socio-political-historical weight, doesn't capture all of Mad's magic, which could be as much about goofy silliness. Among the ones that have stuck for life in my mind include the cop in Issue 11's "Dragged Net" announcing a "Stake out!" with a hideous close up of his open mouth with a clichéd cartoon steak laying complete in his maw, and the comic strip musical to the tune of "It Ain't Necessarily So" which goes in part: "Flash Gordon, he flies to the stars! Flash Gordon, he flies to the stars! But I know he's lyin', cause folks who've been tryin', can't even reach Venus or Mars!"

You encounter stuff like this at the right age and it sticks; for another example my image of the hippie era as I learned about it in history will forever be shaped by Dave "Lighter Side of" Berg's evocations of their goofy rangy deluded self-righteous insouciance, right or wrong. Mad's antic "don't take this seriously" style works for youngsters who think they are clever, and youngsters just ready to have expectations upset or notions upended with the magic of unpretentious silliness. It made the world a jollier, more winsome place; we've always needed as much of that sort of popular art as we can get, especially when done as it usually was with Mad with skill, verve, and a basic respect for a reader's intelligence.

Mad continued to deal with real presidents and real issues, and it had been hitting Donald Trump regularly and hard in its newest iteration. Trump insulted Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg by tweeting that America wasn't ready to elect Alfred E. Newman (Mad's goofy mascot who came to appear on every cover) president; Buttigieg purported in his youthful way to not have any idea who Trump was talking about, marking Mad as hopelessly irrelevant.

If one were in the mood to argue with comic book satire you could insist it wasn't fair, didn't deal with issues in a well-rounded way, was anti-Middle America, embued with that smarty-pants mentality of the New Yorker who invented it. Editor Feldstein was proud to believe much of the mentality of the draft-card and bra-burning '60s radical generation was shaped by his magazine.

But Mad's meta-point—that entertainment, marketing, business, politics, middle-class mores, often failed to live up to their own standards or pretentions—was eternal. Even if new issues with new content are no longer being published regularly, the Mad mentality has sunk its roots everywhere in our culture and can never be extirpated, thank Newman. It's as true a case as any of "Mad is dead, long live Mad."

Like most old fans, I stopped picking up new issues a long time ago. But I'll miss it for the world it represented, when a well-conceived periodical package of words and cartooning on paper could not only be supported by an enthusiastic audience but shape the culture in a funnier, zestier, freer direction.

Show Comments (84)