The Fleeting Glory of Trump Magazine

No, not that Trump.

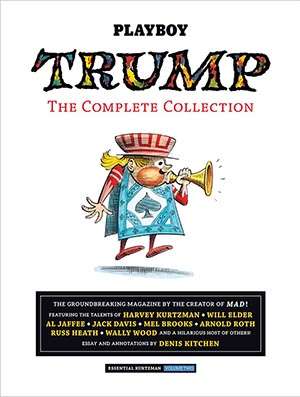

TRUMP: The Complete Collection, edited by Denis Kitchen, Dark Horse Books, 184 pages, $29.99

Trump—the title of which, I feel compelled to point out, has nothing to do with the current POTUS—was an illustrated satirical magazine edited by Mad founder Harvey Kurtzman and published by Playboy's Hugh Hefner. Both men were young, very ambitious, and perhaps a little too idealistic. Thanks partly to a storm of unforeseen business woes that almost destroyed the Playboy empire and partly to Kurtzman and Hefner's generosity toward their contributors, the publication lasted for only two issues, one released in 1956 and the other in 1957. The result, on display in a new collection edited and annotated by Denis Kitchen, was a tragic might-have-been.

Kurtzman is best known for founding Mad, which started out as a full-color comic book satirizing other comics. As one of only two staff editors at the EC Comics company, Kurtzman was expected to write every word of the titles he edited; prior to Mad he ran the imprint's war titles, which often featured anti-war messages. Thanks to his obsessive determination to get all his facts straight, he routinely fell into "research holes." Mad was supposed to be a relatively easy job for him, but he soon started obsessing over it too, especially as he started to run out of comic characters to spoof and began to expand his targets into the worlds of film, TV, advertising, and literature.

Mad was a surprise hit, and it soon attracted attention from outside the marginalized, lowbrow comics world, with Kurtzman becoming a cause célèbre among humorists of all kinds. This, combined with a new industry-wide self-censorship policy (known as the Comics Code) that was threatening EC Comics' very existence, convinced Kurtzman to ask his publisher, William Gaines, to convert Mad from a kiddie comic to an adult humor magazine. Gaines agreed, and Mad became not just more popular than ever but, eventually, a cultural institution. All this sudden and unexpected attention went to Kurtzman's head, and he soon began making outrageous demands that the publisher wouldn't have agreed to under any circumstances, such as 51 percent ownership of Gaines' own company. But Kurtzman thought he had an ace in the hole: Hugh Hefner.

Like most men of that era, Kurtzman was fascinated by Playboy, with its unprecedented mixture of pornography, high-end production values, and intellectual aspirations (or pretensions, take your pick). And Hefner, who had been an unsuccessful cartoonist, was equally fascinated by what Kurtzman was doing with Mad, specifically in the way he would deconstruct—in a very pre-postmodernist fashion—his targets. Kurtzman's commercial purpose was simply to mine humor from his subjects, but if in so doing he also revealed some heaping doses of hypocrisy and greed behind the mass media's messages, then so much the better. (It should be noted here that Kurtzman's parents were Communists. While he never shared their political beliefs, he certainly was raised to view American culture with a cynical eye.)

This approach appealed to Hefner's own self-image as an observant Hip Outsider, and the two men were soon conspiring with each other to create a satirical publication that would put all others to shame, sparing no expense in the process.

Content-wise, Trump wasn't much different than the early "adult" version of Mad that Kurtzman had only just started at EC. Kurtzman also took the cream of EC's stable of artists with him, primarily the incomparable threesome of Will Elder, Jack Davis, and Wally Wood, as well as a young Al Jaffee. (Wood quickly returned to Mad when he learned he wasn't allowed to work for both publications, while Davis and Jaffee were welcomed back after Trump folded. Jaffee still works there 60 years later.) What separated Trump from Mad was the former's determination to be a demonstrably "adult" publication, which meant it included (possibly at Hefner's insistence) a lot of semi-clad young women in the art; the only nod to modesty was a rule against exposed nipples. Mad, meanwhile, slipped back into appealing to a more adolescent audience. This noticeable difference in the sexual maturity of the respective magazines' intended readerships was recreated 15 years later with the arrival of National Lampoon.

One highly ambitious feature from the first issue was an elaborate take-off of Life magazine's illustrated panoramas of various stages of human development over specific time periods. Trump's version imagined what archeologists would make of our own culture, a million years in the future, as they study such "art objects" as fire hydrants and coke bottles and marvel over such "fertility goddesses" as Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell. Being a fold-out feature, it also teased readers into thinking they were opening a Playboy centerfold by inserting a partial photo of a nude model just as you begin to turn the page.

This feature in particular represents the noticeable difference between Trump and Mad in terms of production. The former was printed on slick magazine paper rather than cheap newsprint, and it featured a lot of full-color art in its interiors—hand-colored art at that, which was unheard-of in comic books up until then. So while Kurtzman was generous with his artists, he also was quite demanding, expecting them to turn in the very best quality work they were capable of. Thus, the otherwise slapdashy (but always excellent) Jack Davis employed a far more time-consuming cross-hatching technique instead of his usual water-color approach, with stunning results.

Even more stunning are the incredibly detailed painted illustrations by Kurtzman's childhood friend and lifelong collaborator, Will Elder. Their collaborations in the early Mads still stand out as that publication's most remarkable achievements, and with Trump it was obvious that both men saw this as a golden opportunity to strut their stuff. There's something almost harrowing in the way they would employ a Sistine Chapel–like effort simply to make fun of, say, Howdy Doody or Coca-Cola, and their work in this collection is worth the cover price alone. But Kurtzman and Elder's obsessive, laborious approach was also why Trump (like the Kurtzman-era Mad) was rarely completed by deadline time. You have to wonder how two artists with such an it's-done-when-it's-done-and-damn-the-distributors attitude wound up working in the world of periodicals to begin with. Such prima donnas are more likely to be fine artists—though it's unlikely that these two would have been welcomed in that world either.

Kitchen's collection includes not just the complete run of Trump but also (mostly) unfinished work on what would have been the third issue of the magazine. And there are examples of work in progress from the two existing issues, which serves as a window into Harvey Kurtzman's perfectionist mind. As was the case with the early Mads, he not only wrote and edited almost every feature but also roughed out and/or laid out each piece in great detail. The artists were expected to remain faithful to these blueprints. His sense of timing and composition is flawless, and has served as a go-to model of sorts for visual satirists ever since. The only shame in all of this is the relative lack of Kurtzman's own finished art, since he was convinced the public didn't care for it. (His stock response to anyone who complimented his art was "yeah, you and my mother.") His drawing style was highly expressive and energetic, and he employed it to great effect in dramatic stories as well as humorous ones.

In a sense, Kurtzman's entry into the world of Hefner was both the best and the worst thing that ever happened to him. Yes, it resulted in Trump, but the ultimate differences between the two men—one an unflinching realist, the other a peddler of fantasies—were bound to come to a head at some point. Still, they liked and respected each other, and they continued to work together for decades afterward on the long-running Playboy comic Little Annie Fanny. But that aforementioned conflict of sensibilities always hung over this feature, with one man attempting to enlighten the reader while the other was primarily interested in titillating him.

Kurtzman's later career consisted mainly of various failed or aborted projects. But this never diminished the impact his early work—including Trump—has had on almost everyone in the comedy world ever since, whether they know it or not. He sure has inspired the hell out of me. He is one of America's all-time greatest artists, and he deserves to be a household name.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Fleeting Glory of Trump Magazine."

Show Comments (15)