Making It Easier for Military Spouses To Get Occupational Licenses Could Help All Workers

State-level licensing laws can make it nearly impossible for workers to move from place to place, and that's a particular problem for military spouses. This bipartisan proposal could be a step towards fixing it.

The next Pentagon spending bill Congress passes could contain a few million dollars for tearing down occupational licensing barriers right here at home.

A bipartisan group of lawmakers from both chambers of Congress on Thursday introduced bills that would nudge the states toward adopting uniform, shared licensing standards across a variety of professions. Research on occupational licensing shows that individuals in licensed professions move across state lines less often than other workers—likely because of the time and expense of getting re-licensed in a new state.

Getting locked in place by onerous licensing laws costs all workers, but it's a particular problem for military spouses.

"I followed my husband and that meant sacrificing what I'd worked so hard to achieve," says Brittany Boccher. She'd worked as a teacher in Texas, but gave up that profession years ago when her husband was transferred to a base in another state. Now, after being married 14 years, she's lived in nine different places.

She would love to continue teaching, but Boccher says it's just not practical to get relicensed each time the military sends her husband somewhere new.

She's hardly alone. As I detailed in a Reason feature two years ago, about 35 percent of all military spouses work in licensed professions. About 56 percent of that group work in health care and another 29 percent, Boccher among them, work in education. Every state requires people occupied in those professions to be licensed by the state in which they work. The requirements rarely match up perfectly between any two states, with many states requiring license applicants to go through redundant and expensive training classes.

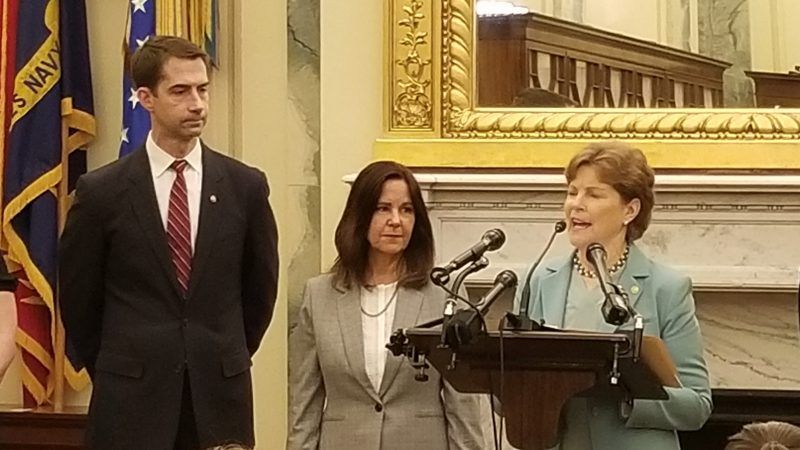

The Portable Certification of Spouses Act aims to change that. Sens. Tom Cotton (R–Ark.) and Jeanne Shaheen (D–N.H.) want to give the Pentagon $10 million for the purposes of setting up interstate compacts for specific professional licenses. The compacts would try to smooth out differences between state licensing laws—something that could benefit all workers in the long run—and create reciprocal agreements among states to honor out-of-state licenses for military spouses.

Cotton says making it easier for military spouses to find new jobs in their fields will help servicemembers better balance their own career interests with those of their wives and husbands.

"We're asking them to move," says Karen Pence, the second lady, who voiced her support for the bill at a press conference held Thursday. "This isn't a handout, it's a way to help them stay employed."

She's following in the footsteps of former First Lady Michelle Obama and Jill Biden, who in 2013 teamed up to urge governors to pass laws easing licensing requirements for military spouses. By 2016, more than 50 state-level reforms had been enacted, reducing licensing and credentialing barriers for military members, veterans, and their families. Since the early days of the Trump administration, groups like the National Military Family Association, a Virginia-based nonprofit that works with currently serving members of all branches and their spouses, have seen interstate compacts and streamlining of licensing requirements as the "next logical step."

"If successful, the bill would reduce the strain of regulations for every American who moves to a new state," write Shoshana Weissmann and Jarrett Dieterle, staffers at the R Street Institute, a free market think tank, in a Wall Street Journal op-ed about the bill. "Once the compacts are up and running, they would apply to anyone, not only military spouses."

Some states are already making progress on recognizing out-of-state licenses, but congressional action could spur more reforms that help all workers—in the same way that the earlier round of military spouse-focused reforms helped lay some of the groundwork for the cornucopia of licensing reforms across the U.S.

Is spending $10 million on this sort of project a core function of the Pentagon? Probably not, but, pound for pound, it's likely a better use of the department's bloated $700 billion budget than far more expensive expenditures. The bill's supporters say the limited timeline is another benefit—funding would expire after five years. If the project doesn't prove to be worthwhile, it can be abandoned.

It's too bad more of the Pentagon's initiatives don't work that way.

Show Comments (11)