Occupational Licensing Locks Workers in Place. Here's One Idea for Fixing That.

Workers in professions requiring state-issued licenses are 36 percent less likely to move across state lines than workers in other jobs.

Workers whose jobs require a state-issued license lose out on between $178 million and $711 million they could have earned by moving to a different state, according to a new paper by two labor economists at the University of Minnesota.

Occupational licenses make it harder for workers to pursue opportunities because getting licensed in another state often requires retaking classes and other time- and money-consuming requirements. Researchers have identified that phenomenon before—including in this wide-ranging report from the Brookings Institution—but the new working paper by Janna Johnson and Morris Kleiner takes a stab at figuring out exactly how many workers those state rules hurt.

Johnson and Kleiner examined 22 professions that are licensed across most states. Workers in those professions are significantly less likely to move across state lines than workers in other, non-licensed professions.

"For example, a licensed public schoolteacher with a decade of teaching experience in New Hampshire is not legally allowed to teach in an Illinois public school without completing significant new coursework and apprenticeships," they write. "The existence of such requirements could constitute a significant cost to migration across state lines for those in licensed occupations, and these costs could prevent individuals from moving if the costs of re-licensure had been lower."

Though migration rates vary from profession to profession, the researchers conclude that the between-state migration rate for individuals in occupations with state-specific licensing exam requirements is 36 percent lower than the rate for other workers. If so, that means more than 100,000 workers are passing up the opportunity to move each year, potentially leaving hundreds of millions of dollars of potential earnings on the table.

In fact, the numbers are likely larger. As Johnson and Morris note, their research fails to capture the lost productivity and earnings for people who are forced out of the labor force entirely because they cannot (or choose not to) get relicensed in a new state. If a wife moves to a new state for a better-paying job, for example, her husband who previously worked in a licensed profession might have to change careers entirely.

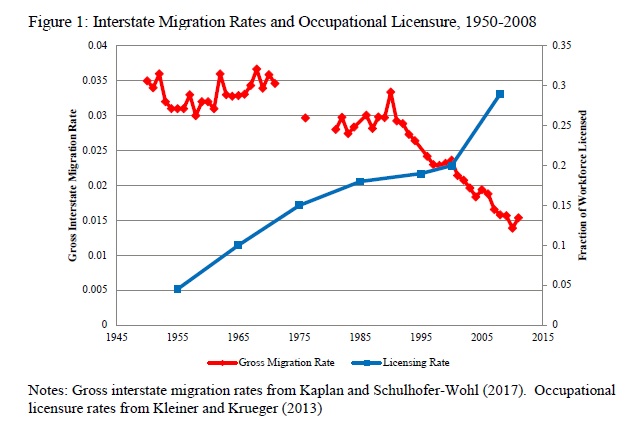

Licensing is probably not the sole cause of the recent drop in interstate migration by Americans, but it certainly seems to be a contributing factor. As earlier research by Kleiner showed, the percentage of jobs requiring a state-issued license has grown from about 10 percent in the 1970s to around 30 percent today. Meanwhile, the percentage of Americans moving from one state to another in a given year has fallen by about half since 1990.

The best solution would be to scale back the number of occupations where state-issued licenses are required. I understand why people want to license professions where there is a serious risk to public health and safety if a worker messes up, but I don't think the risk of a bad haircut really fits the bill. For professions that fall short of that benchmark, voluntary certification or mandatory bonding can serve the same purpose as licensing, but without creating big barriers to entry or limiting workers' ability to relocate.

And if that's too much to ask, Johnson and Morris offer a more modest solution. They found that reciprocity agreements between states—like the one that allows lawyers to practice across state lines with limited relicensing costs—increase the mobility of workers in that profession. That's something the Federal Trade Commission has been encouraging states to consider as well.

Moving requires a substantial investment of time and money even in the best of circumstances. The government shouldn't be adding to that burden.

Show Comments (20)