Anti-Porn Republicans Haven't Gone Anywhere

The porn wars haven't died, they're just packaged differently.

There's been a "total abandonment of pornography as a battleground in America's culture war," writes Politico reporter Tim Alberta in "How the GOP Gave Up on Porn." He couldn't be more wrong.

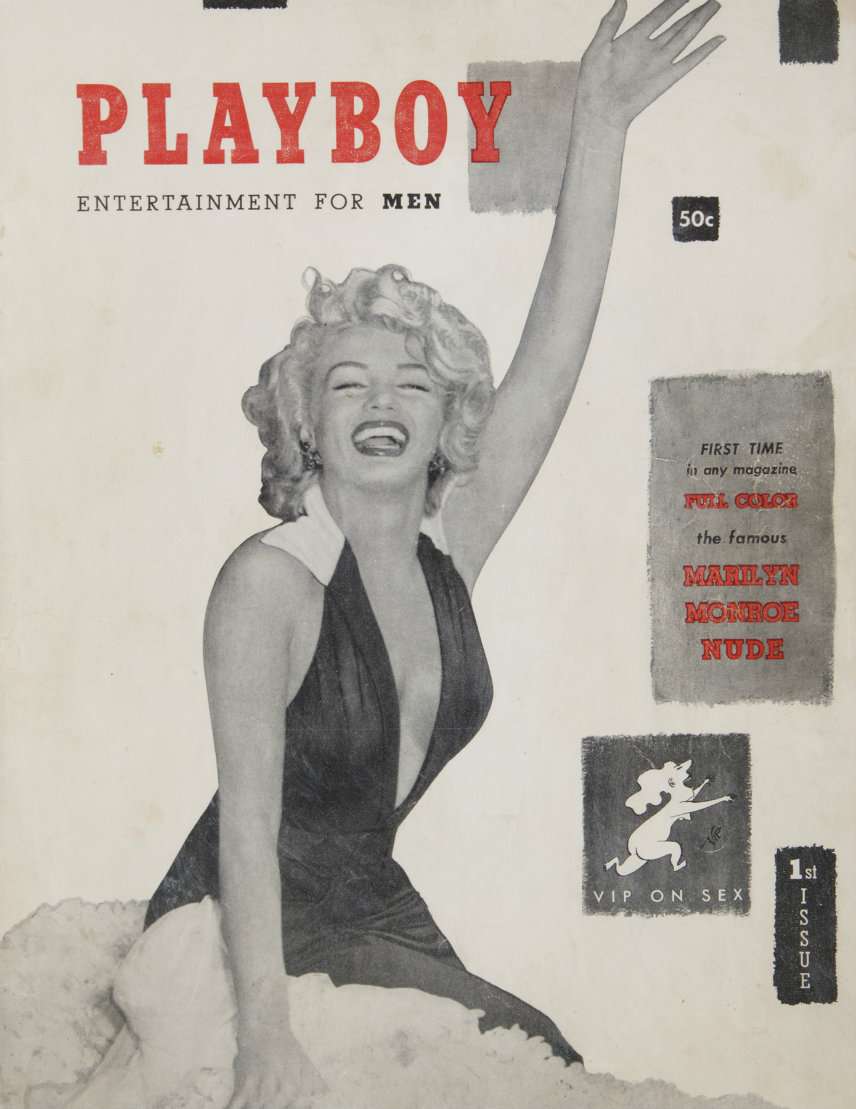

The flashpoints have shifted certainly since the 1970s and '80s, when Jerry Falwell's Moral Majority teamed with second-wave feminists to take on Playboy and Hustler. And social conservatives' embrace of President Donald Trump does present a stark contrast to earlier eras. Alberta notes that while that Falwell sprung to action in response to a Jimmy Carter interview in Playboy ("a salacious, vulgar magazine that did not even deserve the time of his day," the pastor called it), Jerry Falwell Jr. has praised Trump despite the president's vulgarities, even posing with the president in a photo in which Trump's '90s Playboy cover can be seen.

But such hypocrisy should not be mistaken for a radical repositioning of Republican dogma on "obscenity." The dreams of Falwell Sr. and his radfem counterparts are still very much alive in the Republican Party.

"Over a decade spent covering Republican politics," writes Alberta, "I struggle to recall instances of politicians calling attention to pornography. The lone exception: Diane Black, a congresswoman running this year for governor of Tennessee, blamed the rise in school shootings on adolescent porn habits. She was widely ridiculed and ultimately lost the GOP primary. Her comment was a cautionary tale."

Perhaps Alberta should search his memory (or Google) a little harder. After all, it was just two years ago that Republicans added language to their official party platform that declared porn "has become a public health crisis that is destroying the lives of millions."

That same year, 2016, a Utah Republican lawmaker convinced his colleagues in the state legislature to declare porn a public health crisis. Since then, six states—Arkansas, Florida, Kansas, Tennessee, South Dakota, and Virginia—have passed similar resolutions (something Alberta devotes several paragraphs to near the end of the article, despite his earlier quote about Diane Black standing alone).

In 2015, the National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE), formerly Morality in Media, organized an anti-porn summit on Capitol Hill—picking back up an event it had abandoned in the late '80s. Prominent Sen. Chuck Grassley (R–Iowa) was the summit's honorary sponsor. Since then, NCOSE has celebrated getting Walmart to remove Cosmopolitan from checkout aisles, under the rationale that the magazine is too racy for general audiences.

Last year, Republicans in at least a dozen state legislatures introduced measures to ban porn access for anyone who wouldn't pay a $20 fine, and Utah conservatives called for reappointing a statewide porn watchdog.

This year, the conservative New York Times columnist Ross Douthat advocated banning porn. And a search on Congress.gov for the 2017-18 legislation mentioning "pornography" turns up 93 results. (Douthat's column has a cameo in Alberta's article; those 93 results do not.)

But never mind reality. Fresh from declaring that there's been no recent Republican action against porn because he doesn't personally remember it, Alberta gets right to theorizing about why: The right has "surrendered the fight on many social issues as America has moved left" and the anti-porn movement, like "traditional marriage and supporting prayer in public schools," has been tossed aside. This ignores the fact that anti-porn activism of yore was often a bipartisan cause, with second-wave feminists serving as major drivers of the issue; the fact that many in the academic and feminist left still oppose pornography; and the fact that even in recent years, mainstream liberals have worked with Republicans and on their own on all sorts of anti-porn actions.

In California, a coalition of left and right activists fought to make condom use a requirement in all porn films and to appoint a "porn czar" to monitor for violations; the same activists then turned their sights on Nevada. In Dallas, the city council and Democratic mayor supported banning an adult entertainment expo from its Convention Center.

Around this same time, the FBI was running dozens of its own Dark Web porn sites in a massive (if misguided) attempt to catch people sharing pornographic images of minors.

One could credibly argue that there's been less focus on the horrors of naked ladies per se and more on stopping exploitation. But this shift seems more predicated on limited resources and accepting technological realities than a waning impulse to control the sexual lives of others.

Let's not forget Operation Choke Point, an Obama-era program that covertly pressured banks and payment processors to end relationships with porn actors, sex toy sellers, and others in adult entertainment and novelty industries. The initiative represents one of many ways the federal government has been trying to go after legal sex work and adult industries by choking off their access to digital infrastructure. This year a bipartisan group of legislators took aim at sex workers' access to web hosting and advertising with FOSTA, an act alleged to target sex trafficking that actually ensnares adult advertising of all sorts.

Plenty of porn-adjacent panics have sprung up since the 1990s as well, and plenty of political effort has gone into fighting them. So, yes, we might have fewer federal obscenity prosecutions, but we also have many more federal sex crimes on the books overall and no shortage of activity on their behalf. Since 2000, we've seen an ever-escalating federal war on prostitution, all sorts of panic (and prosecutions) over teen sexting, and dozens of bills introduced (in Congress and statehouses) to bring "revenge porn" and "sextortion" to an end.

For instance, last year the House overwhelmingly voted in favor of a bill that would have subjected teen sexters to a 15-year mandatory minimum prison sentence. Republican Sen. Richard Burr moved to expand FBI data-collection practices used in terrorism and national security matters to include investigations into teen sexting. And underage teens who send racy pictures to one another are routinely threatened and arrested under child pornography laws.

Alberta blames Bill Clinton for the proliferation of porn in the 1990s, but he admits that the Clinton administration intensified efforts to eradicate child pornography as general obscenity charges fell. Many of those efforts wound up problematic in practice, but this conception—that the government should stress less about the erotic activity of consenting adults and instead prioritize preventing the exploitation of underage people—is in line with the direction mainstream America was going in the 1990s and largely continues along today.

Many of those 1970s and 1980s anti-porn crusaders have used this to their advantage in fighting against attempts to decriminalize commercial sex. For going on two decades, efforts to reframe all prostitution as "sex slavery" or "human trafficking" and to inflate instances of underage and forced prostitution have been a bipartisan affair, reinvigorating the old coalition of religious conservatives, sex-negative feminists, law enforcement, and concerned citizens easy to amp up over any cause that invokes The Children.

And invoke the children Alberta does. After ascribing to porn all sorts of negative and at best unproven, at worst thoroughly debunked effects (he says it contributes "to abusive relationships and the fracturing of families" and that it incites "destructive behavior," including violence, misogyny, and child abuse), he turns to fears over Generation Z growing up exposed to so much porn. Lots of experts are very, very afraid, and lots of people feel intuitively that the kids aren't OK.

But data actually supporting all those fears have been scarce to nil. And in the same decades that access to porn has dramatically increased, rates of everything from domestic violence to sexual assault to crimes against children (including sex crimes) have fallen.

So Alberta uses the trick many prohibitionists play when there's no actual evidence to support their claims: Follow vague murmurs about grave harm with concrete statistics about ancillary things. Hence, we get six straight paragraphs on the size and scope of the porn industry, how much money porn makes, how many people claim to consume it, and how many people allege in polls that they disapprove. Alberta concludes that "if ever there were a national dialogue needed about porn—if ever there were a moment for some opportunistic politician to make a cause of it—the time would be now."

With all the legitimately pressing problems facing America today, it's astonishing that anyone could earnestly advocate for more obscenity prosecutions and renewed cultural fighting over pornography. But here we are. Alberta has little clue what's been going on in porn politics this millennium, but he's sure that something more must be done.

Show Comments (92)