Under Trump, Republicans Become the Party of 'You Didn't Build That'

Trump's trade policies are supported by a majority of GOP voters, who used to oppose this sort of corporate welfare under Obama. Partisanship rules all.

For at least the past decade, Republicans have positioned themselves as the defenders of what passes for laissez faire economics in modern Washington. During the Obama administration, the GOP attacked new environmental regulations as hidden taxes on American businesses, decried the stimulus as cronyism on a grand scale, and lashed out at a president for claiming that Americans "didn't build" successful enterprises without government assistance.

Now, with President Donald Trump walking the nation to the precipice of a trade war—one that sees America pitted against not only a longtime Republican boogeyman, China, but also such major trading partners as Canada, Europe, and Mexico—congressional Republicans have a choice to make. They can embrace free markets, or they can can embrace Donald Trump.

A trade war will cause significant pain for American businesses and consumers. It will create new hidden taxes in the form of the costs tariffs impose on consumers. It will be cronyism on a grand scale, with Trump and his top advisers deciding which industries get protected and which get crushed. And it is premised on the same idea that angered so many tea partiers when Obama expressed it. Trump hasn't said "you didn't build that," but his actions suggest that America can't build much of anything—steel, cars, the list goes on and on—unless the government steps in with some protectionism.

What will Republicans in Congress do? For most of them, probably nothing.

But some of them are going to try to pull the party in a different direction. Sen. Bob Corker (R-Tenn.), who on Saturday described news coverage of Trump's trade policies as "like something I could have read in a local Caracas newspaper last week," says he is prepared to work "with like-minded Republican senators on ways to push back on the president using authorities in ways never intended and that are damaging to our country and our allies."

I am working with like-minded Republican senators on ways to push back on the president using authorities in ways never intended and that are damaging to our country and our allies. Will Democrats join us?

— Senator Bob Corker (@SenBobCorker) June 2, 2018

It is, for now, unclear what that plan might look like. Still, the statement signals at least a willingness to do something. Previously, many Republicans responded to Trump's tariff threats merely by expressing their opposition and hoping the issue would simply go away. "I'm not a fan of tariffs, and I am nervous about what appears to be a growing trend in the administration to levy tariffs," Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) told the Louisville Courier-Journal in April, as if he wasn't in a position to do anything about the administration's bellicose trade policies.

It's true that Congress has limited its control over trade policy. In 2015, for example, it enacted a Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) allowing the White House to negotiate trade deals with other countries without congressional interference. Congress doesn't enter the picture until it hold a a straight up-or-down vote on the final product, essentially promising that it won't try to alter whatever deal the president makes.

This was a deliberate abdication of the power granted by Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, which explicitly allows Congress "to lay and collect taxes, duties," and the like. In a previous era, this abdication felt like a pro-trade move: Congress has, traditionally, been more open to protectionist policies (just think about how defensive legislators get about anything in their home districts), while the White House has been more likely to support free trade, since the president tends to get credit (and blame) for the economy as a whole.

"They never anticipated having a protectionist president," says Dan Ikenson, director of trade policy studies at the Cato Institute. Like so much else in the Trump presidency, the trade war is partly a consequence of a decades-long slide of power from the legislature to the executive.

Reversing that trend won't be easy, but if Congress wants to rein in Trump, there is an important deadline looming at the end of this month.

Congress has until June 30 to reauthorize the TPA it passed in 2015. This is supposed to remain in place for six years, but there's a catch: After three years, Congress can exercise an option to revoke that authority. While revoking Trump's TPA would not directly block tariffs—the steel and aluminum tariffs have been issued under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which gives the president more or less carte blanche to impose tariffs on national security grounds—it would be at least a symbolic blow, and an indication that congressional Republicans reject Trump's trade policies.

A more dramatic option would be to pass the Global Trade Accountability Act, a bill proposed by Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah). This would require congressional approval before tariffs could go into effect. The bill would also give Congress the ultimate authority over whether to withdraw from other trade agreements, including NAFTA and the WTO. Again, this would not apply to Trump's Section 232 tariffs, but it could limit the damage the president can cause and it may put America's top trading partners slightly at ease.

But don't get your hopes up. Corker, who is not running for re-election, appears to be in the minority when it comes to standing up for free trade. And he seems to know it—hence his tweet's call for Democrats, who are also in the minority, to come to his aid.

"There is no Republican Party. There's a Trump Party. The Republican Party is kind of taking a nap somewhere," former Speaker of the House John Boehner said last week.

Well, maybe; it depends on which Republican Party you mean. There have been periods when the GOP was a more protectionist party, and even seemingly pro-trade presidents like Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush erected trade barriers at times. But the Republicans discovered a strong free market message during their years as Obama's opposition, and that message is now all but lost.

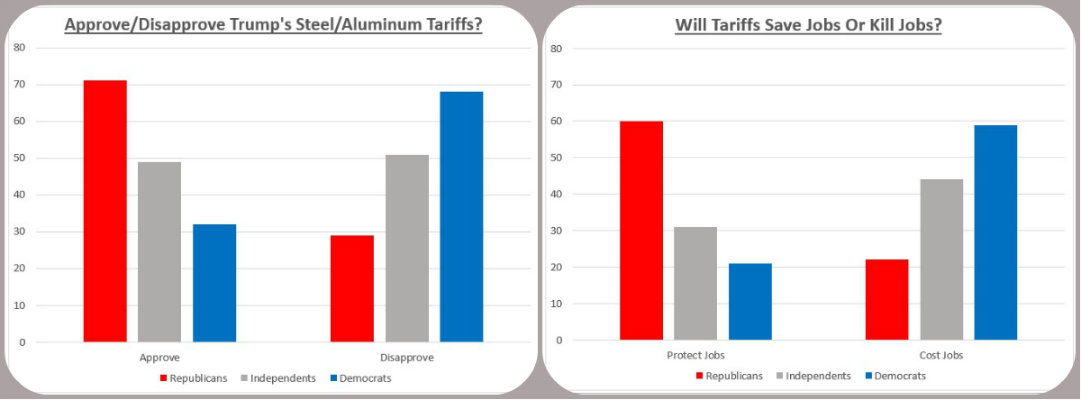

A Harvard-Harris poll released last week found that 71 percent of self-described Republicans approve of Trump's decision to place tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, while 60 percent believe those tariffs "will mostly protect American jobs":

The part about protecting jobs is simply not true. Even if the tariffs do protect some steel-making jobs, they will destroy more jobs in downstream industries, according to projections from both pro-trade and anti-trade groups.

But the first part is what congressional Republicans are hearing loud and clear. On Sunday, House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy took to CNN to defend Trump's tariff plans.

"We are standing up for the process of where we're moving forward that we have fair trade," McCarthy said.

If a majority of Republican voters are going to follow the president into a trade war of choice, then Republicans in Congress appear ready to dutifully stand aside. This year has already seen the GOP abandon its rhetorical role as the party of fiscal responsibility by passing a budget-busting omnibus bill that required the repeal of spending limits once championed by the party's leaders.

Now, in the service of a president pursuing anti-market trade policies, Republicans are casting aside another principle that they recently treated as a clarion call. Just as Republicans seem to be stawart fiscal conservatives only when they are in the opposition, it looks like they might be ardent free traders only when they aren't led by a president who refuses to see the benefits of trade. Republican opposition to big government doesn't seem to have been about anything more than partisanship.

Show Comments (92)