National I.D. By Any Other Name Still Stinks

A patchwork of state-level systems accomplishes what Americans have specifically rejected, and perhaps far more.

There have been many pushes to centralize and standardize our individual identification data at the federal level. But when given the choice, American voters and their representatives have always rejected the idea of National I.D. Alas, that hasn't stopped the government with going ahead with it anyway.

In a new report published by the Cato Institute, Jim Harper of the Competitive Enterprise Institute details how a patchwork of state-level systems and programs that collect and share data already does everything the National I.D. proposals of the past ever hoped to, and is poised to do much more.

Harper's report identifies six different programs that in conjunction with each other can or already do provide federal, state, and local authorities with near-instantaneous access to huge amounts of identifying data. Combined, they form a de facto National I.D.

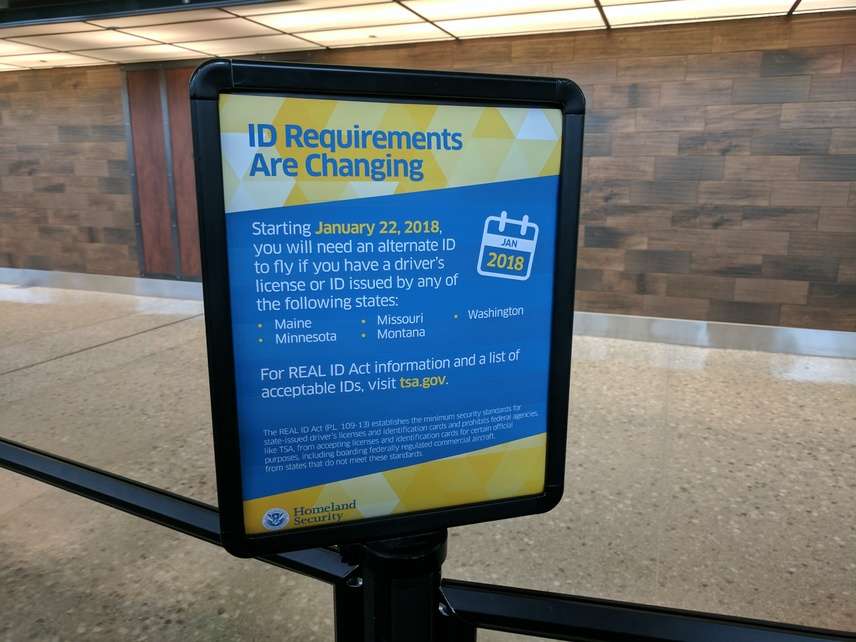

The most familiar (and also most complete) of these systems are the federal REAL ID driver's license standardization mandates and the E-Verify digital employment eligibility checks used by a number of states.

For those who have followed the years-long controversy over REAL ID, the report's most dismaying insight may be that the fight is essentially over. After years of resisting or refusing implementation of the Department of Homeland Security's REAL ID requirements, all 50 states are now in at least partial compliance.

The result, the report says, is a nationwide system in which "even a small-town sheriff in rural Georgia or Vermont could have access to a database of hundreds of millions of Americans' images." Between that and E-Verify, that sheriff could easily tie a face to a Social Security account—a National I.D. measure that voters have vociferously opposed, and that was rejected when it was proposed in the 1970s.

This de facto National I.D. becomes even more expansive when combined with a number of new technologies that states are starting to roll out. Harper discusses the possible combinations of REAL ID and E-Verify with the facial and license plate recognition technologies many states are already using, either in experimental or full-fledged forms.

It's troubling enough that a single license plate recognition unit bolted to a telephone pole on a small town's main street might allow Barney Fife to build an extensive record of residents' comings and goings with minimal effort, or that a facial recognition program tacked onto the New York Police Department's city-wide CCTV network could automatically track and log your walk from Harlem to Chelsea. But a world is fast approaching in which Barney and Bill Bratton can share that information with each other immediately, without any meaningful oversight or restriction.

Show Comments (16)