Regulations Prevent Some People from Using Google Arts & Culture's Portrait-Matching Feature

Illinois and Texas think biometric identifiers are a lawsuit waiting to happen.

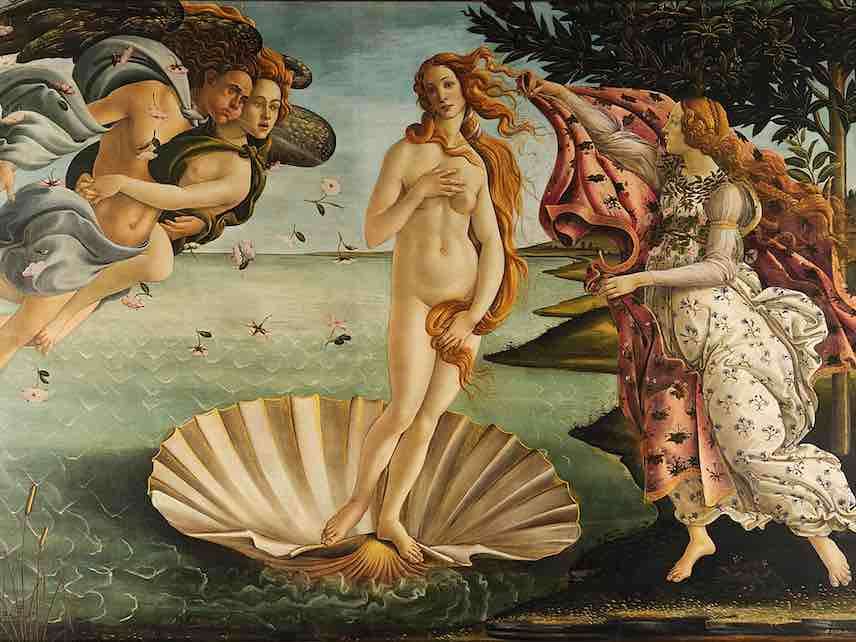

Tons of people recently downloaded the Google Arts & Culture app to discover which famous work of art they resembed, filling the internet with side-by-side images of selfies and portraits. While those in Illinois or Texas may be curious if they look like a Rembrandt portrait or Botticelli's Birth of Venus, Google refrained from releasing this portrait-matching feature in those states due to their stringent biometric regulations.

While the app itself has existed for a few years and offers additional features, the selfie feature went viral as scores of people began posting their accurate, or sometimes cruelly inaccurate (and hilarious) matches on social media. Using facial recognition technology, the app compares the image of its user to the thousands of famous portrairs housed in its database, offering up a series of "matches," so users can find their artistic dopplegangers. But people whose phones are registered in the state Illinois and Texas discovered they were unable to use this feature (though they could ask their out-of-state relatives to find their matches for them).

That's because the app uses biometrics or "biometric identifiers," according to the National Law Review, which include fingerprints, voiceprints, and facial geometry that can be used to identify a specific individual. Illinois in particular has led the forefront in biometric privacy lawsuits and regulations—having passed the illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act ("BIPA") in 2008. While other states like Washington and Texas have passed their own versions of BIPA, Illinois remains the most onerous. As a result of this legislation, companies like Facebook, Shutterfly, and others have all been the target of large class action lawsuits regarding their use of biometric data.

Though Google requires users to accept a disclaimer before using the feature that states the app only stores data as it actively seeks for matches, the company feared these security measures may not be enough to satisfy Illinois law. Unlike other states, in Illinois BIPA allows private citizens to sue companies for damages, when typically suits of this nature must be brought by the attorney general of that state.

Consequently, this regulation has deprived citizens of Illinois from enjoying other, possibly more useful features and products. Nest—another company specializing in thermostats and home security—declined to sell a doorbell technology that can recognize visitors in the state.

According to BIPA and the National Law Review, BIPA is an essential regulation, because unlike Social Security numbers and passwords that can be changed if necessary, biometrics are biologically unique and, when compromised, leave an individual without recourse, making this type of potential identity theft all the more dangerous.

But there are tradeoffs. As Matthew Kugler, an assistant professor at Northwestern University's Pritzker School of Law, told The Chicago Tribune, "(Maybe) people would much rather have their selfie feature than this privacy protection. That's something we'll have to see."

Show Comments (12)