Off-Duty Cops Ought to Pay On-Duty Consequences

New York police officer to be arraigned for an alleged assault at a bar.

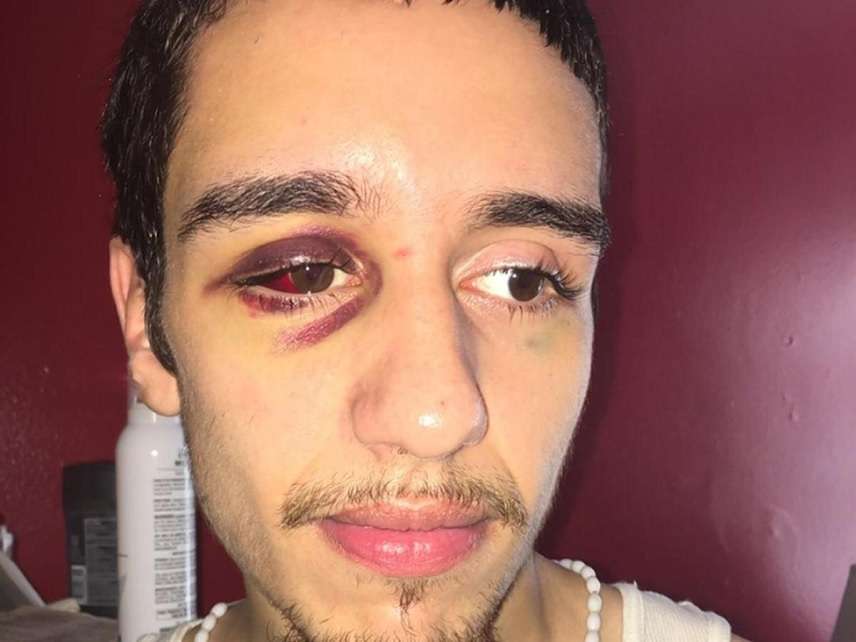

A New York police officer is expected to turn himself in today, to be arraigned on charges related to his alleged assault of a man whose friend might have spilled a part of his drink on the cop's shoe.

The cop, O'Keefe Thompson, was already on some kind of desk duty due to an unspecified illness or injury that precludes him from active work but apparently doesn't preclude him from going to a Coney Island bar and giving a man a concussion.

The case—hardly the first time an NYPD cop has been accused of off-duty wrongdoing—illustrates the importance of an effective police disciplinary process. A criminal indictment ought to be sufficient grounds for a police department to decide to terminate an officer. Cops should certainly enjoy the due process rights they often deny others. But there is a difference between the due process required before the government can deprive a free person of his life or liberty, and the due process requires before the government can deprive a person in its employ of his employment.

Such a high burden of proof, unfortunately, is often required to terminate bad cops. This is dangerous, not only because it keeps bad cops on the street but because it increases the pressure on prosecutors to pursue charges even when they may not have the evidence needed to secure a conviction.

Something is wrong when the only two options for dealing with an abusive cop are a slap on the wrist or a criminal conviction.

Cops should certainly not be protected from prosecution, as they often appear to be now. There is also something unsavory about the bench trials cops often request instead of facing a jury. Judges rarely punish or convict police officers, as seen in the recent case in St. Louis where a now-former officer was accused of planting a gun on a man he shot and killed, and was caught on tape saying he would kill the man moments before. The judge nonetheless let him off. No cop has been convicted in a bench trial since 2005.

A few months ago in New York, a judge cleared two officers who were caught on tape beating up a postal worker after finding out he had inadvertently given directions to a maniac who had killed a cop. The officers claimed they stopped the postal worker because he was parked in front of a hydrant, writing him tickets for that and other alleged traffic infractions.

Nor should it matter that Thompson was off-duty when he allegedly assaulted that man in a bar. How officers behave off-duty is a reflection not only of how they behave on-duty, but of the standards they expect to be held to. Being part of the criminal justice apparatus should not mean deferential treatment when someone ends up on the other side of the system. In many jobs, criminal charges are sufficient for a termination. For employees of the criminal justice system, perhaps it ought to be required.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Being part of the criminal justice apparatus should not mean deferential treatment when someone ends up on the other side of the system.

However, being part of the State Department apparatus should.

I imagine Thompson will lose his job after he fails to show up because he's in jail for assault.

He's saved up a ton of assault leave.

I imagine you're going to be very disappointed when the cop is acquitted and given a medal for gravely stopping the aggressive advancement of the guy's face with his fist.

His buddy assaulted the brave officer's shoe with his drink. Guilt by association makes the "victim" guilty of assaulting a cop. Can't have people assaulting police officers, or be associated with people who assault police officers. Even if they don't know the person is a cop. That's no excuse. Assault on a police officer, even by association, means that person will soon be raping children in front of their mothers before killing the entire family. So the brave officer would have been totally justified in killing both of these men. Because he didn't entire families will be raped and murdered.

No government employee should get these benefits of the doubt.

They all do.

Jury trails on the state level in another district should be required for cops and other bureaucrats.

As Kray-Kray points out in the article, on-duty consequences are always nil.

"The officers claimed they stopped the postal worker because he was parked in front of a hydrant, writing him tickets for that and other alleged traffic infractions."

Based on cop logic, this means the police officers in question should forgo any mail service since they don't like postal workers.

"...forgo any mail service since they don't like postal workers." and fire protection too.

Didn't see a fire hydrant in the video. Another cop lie?

No cop has been convicted in a bench trial since 2005.

Professional courtesy.

Many jurisdictions allow off-duty cops to get special privileges but none of the consequences when they use said privileges to violate someone else's rights.

A cop must have zero tolerance for public slights, because an insult to any one of them is an insult to the entire organization, and to the boss himself, and that can't be...no, wait, that's the Mafia.

Off duty or on-duty WTF is the real difference? The "alleged" act ;-( involved a cop who was likely intoxicated, while backed-up by "good cops" (it's a pack thing) who stood there and didn' do nuffin' while the hero cop was takin' care of business by protecting patrons' safety from dangerous beverage spillage. Thankfully, workers' comp coverage and maybe the time clock are missing factors.

How about a strike(s) law for law enforcement.

Is there a surgeon general warning about mixing steroids with alcohol and/or psychopathy?

How about a specific law - no bench trials for felonies. If you want to contest felony charges against you, use a jury.

And how about another specific law - local elected officials (mayors, county commissioners, etc.) should be able to send any cop in their jurisdiction to desk duty for any length of time, for any reason (except race, religion, political affiliation and the like). If the cop wants to ride around the streets confronting citizens he should then have to get a job in another jurisdiction which can likewise take him off the streets if it wants.

I keep hear that being a cop is a 24 hour a day job.

It stops when they punch out. Hey-o!