Released From Prison But Locked Out of Work

How licensing laws that block people with criminal records harm the formerly incarcerated and the economy.

When the state of Illinois turned Carlos Romero's life upside down in 2013, he had been out of prison for more than 20 years.

He had done two years at the Western Illinois Correction Center for attempted murder. His conviction, in 1991, was for shooting another young man during an altercation in the streets of his poor Chicago neighborhood the year prior. He ended up serving less than half of his six-year sentence, released early for good behavior and put on probation. That was small consolation to the then-22-year-old Romero, who recalls that getting out of prison felt like having "an out-of-body feeling I couldn't shake."

His conviction had ended his dreams of getting out of Chicago and seeing the world. When he reported to the Western Illinois Correction Center on April 15, 1991—a date Romero says he'll never forget—it was less than a year after he'd finished his GED and signed up to join the military. Leaving the same prison during the summer of 1993, he felt like "everything and everyone had changed."

Romero got to work putting his life back together, trying to escape the mistake that would continue to stalk him for the next two decades. He lived with his sister for a while, and like many former convicts, he struggled to find work. He was in his early 20s, with little meaningful work experience, no college degree, and a criminal record. It was months before he landed a gig with a temp agency doing translation, and he worked his way from there into a variety of manufacturing jobs, allowing him to eventually live on his own.

By 2010, when Romero began studying to become a respiratory therapist—a medical professional who works with patients suffering from a wide range of lung diseases or recovering from injury or surgery—he had been a free man for 17 years and for the first time felt like he'd found a true calling. A year later he started working at St. Bernard Hospital in the Englewood neighborhood on Chicago's South Side. "It did my heart well to see patients that I helped take care of walk out of the ICU," he says.

"He was an excellent therapist. Very nice, very personable," says Doug McQueary, who ran the respiratory therapy program at St. Bernard's during Romero's time working there. Now retired, McQueary says Romero was upfront about the felony conviction on his record but had worked hard to turn his life around. "I admired him," McQueary says.

Just as Romero was settling into his new job, the Illinois state legislature passed a law that would punish him a second time for the crime he'd committed two decades earlier. A Chicago Tribune investigation had found that 16 licensed doctors and nurses in Illinois were on the state's list of sex offenders. In response, the legislature passed an absolute lifetime ban on licensing for any doctors, nurses, therapists, and other health care professionals convicted of any forcible felony. The ban applied not only to new applicants but to all current license holders.

The law was passed in 2011. Romero had his license revoked in 2013.

"I honestly thought it was a paperwork mis-shuffle, because I followed all the guidelines in legally obtaining my license," including telling the licensing board about his time in prison, Romero says. After realizing that it was for real, he told administrators at St. Bernard's and at another hospital where he was working part-time about the situation, hired a lawyer, prepared to fight.

But there was nothing he could really do. The law was clear. He had a forcible felony on his record, so he could no longer do the job that made Romero feel, for the first time since before his conviction, like he was making a positive difference in peoples' lives. His license was revoked and his job was gone. "I was floored, stunned, numb," he says. "I was not worthy of a second chance, a fresh start.

"In short, it fucking sucked."

Romero's experience is not unique. Illinois' decision to retroactively revoke licenses from people who already had them was an unusual step, but most states prohibit the formerly incarcerated from pursuing a wide range of potential careers. So-called "good character" provisions in licensing rules block potential applicants even if they've been out for prison for years and even if their criminal history has little or nothing to do with the licensed profession.

These blanket bans on granting licenses to the formerly incarcerated are a pernicious consequence of two troubling trends of the past few decades: the growth of supposedly tough-on-crime policies that give convicts longer prison sentences and a more difficult road to putting their lives back together, and the growth of occupational licensing as a barrier to finding a job.

Criminal justice reformers have called a host of practices into question, and other reformers have targeted onerous licensing rules that serve as little more than an arbitrary barrier to employment. Now a few states are beginning to consider the intersection of those two issues.

These policies matter even for people who have never been behind bars, since an inmate's job status after getting released from prison is the best indicator of whether that person will commit another crime within three years of being released. Prohibiting former prisoners from pursuing work closes off much needed opportunities for some of the most vulnerable members of society, and in some cases can even push them back to a life of crime.

The Consequences of Licensing Rules Blocking the Formerly Incarcerated From Jobs

More than 600,000 Americans will be released from prison this year. Many of them will face the same struggles that Carlos Romero did.

They don't have anywhere to go, and they face a high risk of homelessness, with little in the way of assets. Those with children, especially incarcerated men, may have accumulated huge child support bills while behind bars. Others might have legal bills or fines to pay.

The best way to deal with all those problems is to find a job, but newly released prisoners face a difficult road to employment, because businesses are generally hesitant to hire the formerly incarcerated. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, between 60 and 75 percent of released prisoners remain unemployed one year after getting out.

"For a myriad of reasons, stable employment is of central importance to the successful reentry of former inmates into noninstitutionalized society," writes UC Berkeley public policy professor Steven Raphael in The New Scarlet Letter: Negotiating the U.S. Labor Market with a Criminal Record. "The material well-being of most released inmates depends principally on what they can earn in the labor market."

Raphael says the likelihood of committing a crime depends, to some extent, on whether an individual has something to lose. "Those with good jobs and good employment prospects in the legitimate labor market tend to commit less crime. Those with poor employment prospects tend to commit more." Recidivism is often driven by the need for income, or because the fear of being caught and punished means little for someone who has nothing and no prospect of employment.

That's one reason why 68 percent of released prisoners commit another crime within the first three years after getting out of prison. Aside from the social cost of those crimes, there is a very real fiscal cost. Estimates vary, but The Pew Center for the States figures that states could save $15 million by reducing recidivism just 10 percent. So state governments have invested in a cottage industry of job training programs aimed at helping inmates learn valuable skills and even earn degrees while they are behind bars.

Those programs can be helpful, but they only overcome one aspect of an inmate's reintroduction into the labor force, says Stephen Slivinski, an economist at Arizona State University.

Readjusting to a life of freedom and staying away from crime is made more difficult by government policies that block the formerly incarcerated from finding work. In 29 states, occupational licensing boards are allowed to reject applications from anyone with a felony conviction. Slivinski notes that there tends to be an inverse relationship between a state's overall licensing burden and the ease with which a former prisoner can get a license. That is, states with the toughest burdens for the formerly incarcerated are often states with generally lower occupational licensing burdens across the board, though there is wide variance in both categories from state to state.

The result is that many formerly incarcerated individuals are prevented from pursuing work as barbers, roofers, massage therapists, or health care professionals. Even those who do get licensed, like Romero, run the risk that a change in state policy will leave them out of work again.

Slivinski is the author of a first-of-its-kind study into the relationship between recidivism rates and state occupational licensing burdens, which shows the higher-than-average hurdles faced by former prisoners. After reviewing licensing rules and recidivism rates across all 50 states for a 10-year period beginning in 1997, Slivinski found that ex-cons are more likely to commit a new crime if they live in a state with strict licensing rules.

Over the decade of his study, the country's average recidivism rate rose by 2.6 percent. In the 29 states where licensing boards can reject outright applications from anyone with a felony conviction, the recidivism rate rose by a whopping 9.4 percent; it actually declined by 4.2 percent in states without those "good character" provisions.

"The government-imposed hurdles for ex-prisoners will remain, regardless of education attainment or skill level, if the so-called 'good character' provisions remain," says Slivinski.

"State licensing schemes that mandate criminal background checks theoretically aim to protect public health and safety, but, far too often, restrictions are unnecessarily expanded without any benefit to public health and safety."

We don't know how many people apply for a license and get turned down, and we don't know how many former prisoners are blocked by licensing boards. But there are a number of reasons to suspect both numbers are very high.

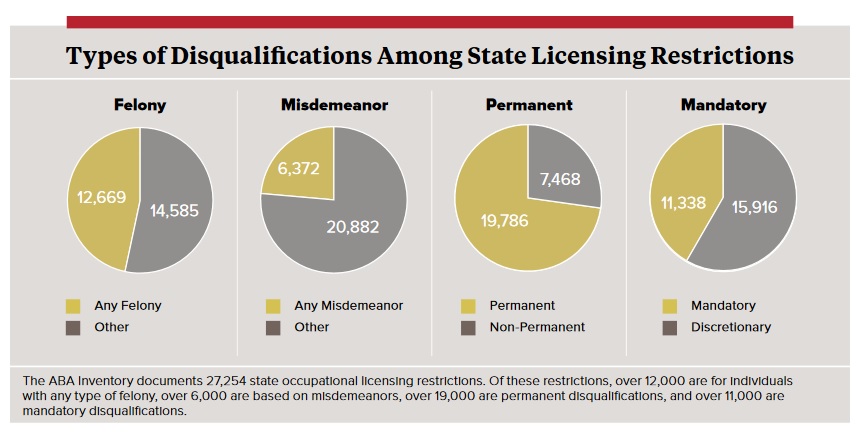

The American Bar Association estimates that there are about 32,000 state licensing laws that include provisions that consider applicants' criminal records. Not all of those are the "blanket bans" that stop anyone with a record from getting a license, but it suggests the scope of the problem. Meanwhile, more than 77 million Americans have a criminal record, according to the FBI.

Licensing laws have proliferated in recent years, driven by policy makers' efforts to protect citizens from threats that do not always exist. Almost a third of all jobs in America today require an occupational license, up from only about 10 percent of jobs in 1970, according to research by Morris Kleiner, a labor economist at the University of Minnesota.

"State licensing schemes that mandate criminal background checks theoretically aim to protect public health and safety," says Beth Avery, a staff attorney for the National Employment Law Project, a left-leaning think tank that advocates for criminal justice reforms. "But, far too often, restrictions are unnecessarily expanded without any benefit to public health and safety."

She points to the case of Sonja Blake, a Wisconsin grandmother who, in 2010, lost her license to run a daycare because of a 30-year old misdemeanor conviction for failing to report an overpayment of public assistance benefits.

Policy makers, Avery says, should remove laws that impose blanket bans on licensing for the formerly incarcerated. Luckily, in the last few years, some states have begun to take steps in that direction.

How One Man's Story Paved the Way for Licensing Reform in Kentucky

State Sen. Whitney Westerfield, the Republican chairman of the Kentucky Senate's Judiciary Committee, spent years opposing criminal justice reforms that the Democrat-controlled state House would send to his committee. But in 2016, he changed his mind after hearing testimony from a 45-year-old man with a 27-year-old felony.

T

hat man, West Powell, was convicted at age 18 of stealing car radios from an auto salvage yard in Campbell County, Kentucky, just across the river from Cincinnati. Powell was convicted of a felony, and he spent a year in prison.

He remembers being teased by prison guards who told him he'd be back behind bars. Kentucky has one of the highest recidivism rates in the country: More than 40 percent of released convicts return to state custody. But Powell never did.

Yet that youthful mistake has burdened him for decades. "Every time you apply for a job they ask you have you been convicted," Powell told Westerfield's committee in October 2015. "So you lie. You work two or three weeks, four weeks, then they find out and fire you. But three or four weeks of work beats no work. So I did it. I did it for years. Just hopping from job to job."

For years, Westerfield says, he had never thought about how criminal records continued to follow people after they got out of prison. He had dismissed efforts to ease punishments as something that couldn't possibly be in the state's best interest. Westerfield credits Powell's story with transforming him from a critic of criminal justice reforms—a position he now admits was "stupid"—into a champion for easing the burden on people who had served their time.

Powell did "what we ask everyone in the justice system to do, which is not break the law again, and not come back to jail. He'd gone a quarter of a century since then. He put himself through school and provided for himself and for his family," Westerfield says. "It wasn't until I stopped and listened that my mind was changed, and that I saw, frankly, how rational and reasonable and strong those policies could be."

His mind changed, Westerfield crafted a law allowing more than 60 felony offenses to be expunged if a convict has not committed another crime in five years. That bill passed last year. He then ran a legislative commission that produced a major licensing reform, SB 120, which Gov. Matt Bevin signed in April. It removes the state's blanket ban barring anyone with a criminal record from entering more than 50 different lines of work: everything from barbers to HVAC technicians to land surveyors to radon inspectors.

"It was a needless impediment to employment," Westerfield says.

The new rules still allow boards to take an applicant's criminal record into account when deciding whether to issue a license. But it gives each person the opportunity to make their case before the board.

The change was driven not just by personal stories like Powell's, but by economic reality. "Kentucky has a jobs problem," says Bill Lear, chairman of the state Chamber of Commerce. Lear says employers often cannot find anyone to fill the estimated 110,000 job openings across the state. Business groups do not have a track record of getting engaged in criminal justice issues, but Kentucky's low labor force participation rate—it ranked 47th in the country last year—helped convince Lear's group to back the bill.

The new law also lets low-level felons hold jobs while incarcerated, with businesses invited to operate inside prisons or through work-release programs. In addition, it prevents defendants from being locked up simply because they cannot pay court costs.

Giving a second chance to someone with a criminal record, Lear argues, gives them "a chance to become more productive citizens, pay taxes, and support their families."

"This has nothing to do with issues that divide partisans. Everybody wants people who are in jail to not come back to jail. Everybody wants people who were in jail to go back home and lead successful lives."

Even law enforcement lobbyists and victims' advocates, two groups that usually oppose any effort to soften punishments for convicts, supported SB 120. With such wide support, the bill breezed through both chambers of the state legislature.

"This has nothing to do with issues that divide partisans," says Westerfield. "Everybody wants people who are in jail to not come back to jail. Everybody wants people who were in jail to go back home and lead successful lives."

Building a System That Makes Better Civilians—Not More Criminals

"More than 95 percent of the people currently locked up are getting out someday, whether you like it or not," says Holly Harris, executive director of the U.S. Justice Action Network. "That's reality. You face that reality and you ask whether you want to build a system that makes better criminals or better civilians."

Since 2015, 17 states have adopted so-called "Ban the Box" statues prohibiting public agencies from seeking information about job applicants' criminal histories. Those changes have shown that allowing former prisoners to pursue a wider range of jobs can indeed improve a state's economy. A study by the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C., found that Ban the Box policies are correlated with a four percent increase in employment in high-crime areas.

While "Ban the Box" has opened new pathways to employment for the formerly incarcerated, easing licensing rules could do much more, given the wide range of jobs that now require licenses. It would also fix a major inconsistency. If government entities are not allowed to ask about applicants' criminal records, then why should quasi-government entities like licensing boards be allowed to deny applicants solely because of crimes they once committed, even long after they've paid their debt to society? Better for individual employers to decide who they want to hire than to have licensing boards preventing that conversation from ever happening, because all signs indicate that, given a chance, at least some of those former prisoners will find work.

A 2008 study from the Center for Economic Policy and Research, a left-leaning think tank, found that the United States has "lost as many as 1.7 million workers due to employment barriers for people with criminal records." If all those workers could rejoin the work force, the national unemployment rate would fall by a full percentage point, the researchers found.

On a local level, the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia found in 2011 that securing jobs for only 100 formerly incarcerated people in the City of Brotherly Love would net $55 million in lifetime earnings and more than $2 million in future tax revenues, while saving at least that much annually by keeping those same people out of the criminal justice system.

That's an argument that should appeal not only in labor-starved Kentucky, but to politicians everywhere.

In Nebraska, Laura Ebke, the state legislature's only Libertarian member, introduced a bill in January to implement many of the same reforms as the Kentucky measure. "We want people to get out of prison and be able to have jobs," she says. Besides Kentucky and Nebraska, seven other states have seen such proposals introduced this year, though only Kentucky's has become law.

Reformers say there are some circumstances where there are genuine health and safety reasons to deny a license to an ex-convict. "There is nothing wrong with developing laws and regulations that directly address the issue of safety," says Beth Johnson, director of legal programs at Cabrini Green Legal Aid, a Chicago-based nonprofit that helps individuals with criminal records find jobs and support services. Someone convicted of embezzlement reasonably can be blocked from becoming a licensed accountant, Johnson says, just like someone with a record of DUI could be stopped from becoming a truck driver.

But why should an embezzlement conviction prevent you from becoming a truck driver, and why should a DUI stop someone from becoming an accountant? "Those lifetime barriers need to have that direct nexus, where the conviction would cause harm to those we are trying to protect," says Johnson.

"Policy makers should refrain from categorically excluding individuals with criminal records, and instead should only exclude those individuals whose convictions are recent, relevant, and pose a threat to public safety."

"Policy makers should refrain from categorically excluding individuals with criminal records, and instead should only exclude those individuals whose convictions are recent, relevant, and pose a threat to public safety," Jason Furman, the then-chairman of the president's Council of Economic Advisors, told the Senate Judiciary Committee last year during a hearing on occupational licensing issues.

Giving greater discretion to licensing boards to decide who gets a license and who does not can create additional worries. Boards too often look for any excuse to block applicants, since many professional licensing boards act as gatekeepers to limit competition in certain markets. Avery says policy makers must follow up on reforms by making sure licensing boards are not continuing to reject every applicant with a criminal record, and must provide for an appeals process when an applicant is unfairly ruled out.

Lawmakers Are Realizing That Licensing Requirements Have Unintended Consequences

There was no appeals process for Carlos Romero when the state of Illinois stripped away his license in 2013.

So he created one.

Romero reached out to his local state senator, Iris Martinez, met with her, and eventually convinced her that the Illinois' legislature had been wrong to enact such a broad prohibition in response a handful of sexual assaults.

Then they had to convince the rest of the state legislature. Romero enlisted the help of Cabrini Green Legal Aid, which had worked with him when he was going to school and working towards earning his license. They called for backup from the Restoring Rights and Opportunities Coalition of Illinois, a collection of organizations and activists that work on behalf of those harmed by the criminal justice system. Members of the various groups made weekly trips to Springfield, a six hour round-trip from Chicago, to lobby lawmakers on the unintended consequences of the 2011 licensing law.

The work paid off. By May 26, 2016, when Martinez' bill made it to the House floor for a final vote, even the legislator who had sponsored the original 2011 law had signed onto the reform bill as a co-sponsor.

"There were unintended consequences from that bill," admitted state Rep. Patricia Bellock (R-47th District). "It was probably too broad at the time."

Gov. Bruce Rauner signed the bill in August of last year, and in January Romero was able to begin the process of having his license reinstated. In mid-May, he was the first person to receive his license under the new law.

The legislative victories in Kentucky and Illinois, along with ongoing debates in Nebraska and elsewhere, give hope these unjust and unnecessary barriers can be removed.

"For many valid reasons—economic health, public safety, justice system costs, belief in the American dream—people across the political spectrum are rallying in support of these common-sense reform efforts," says Avery. "It's time government officials responded to their calls for action."

With his license restored, Romero can get back to doing the work that he loves. He's currently interviewing for jobs as a respiratory therapist at hospitals in Chicago.

"I thank God for bringing me through it all and for allowing me to play a small part in making people's lives a bit better," he says. "Having my license restored means so much more now, but suffice it to say that when I received my license it felt that people now see me as I am and not as I used to be."

Show Comments (46)