This Bill Would Protect Medical Marijuana Suppliers From Jeff Sessions' Whims

The bipartisan CARERS Act prohibits federal prosecution of patients and providers who comply with state law.

Today a bipartisan group of senators plans to introduce a new version of the CARERS Act, which aims to protect medical use of marijuana in the 29 states that allow it.

Among other things, the bill would provide a more permanent shield from prosecution and forfeiture than the Rohrabacher/Farr amendment, the spending rider that bars the Justice Department from interfering with the implementation of state medical marijuana laws.

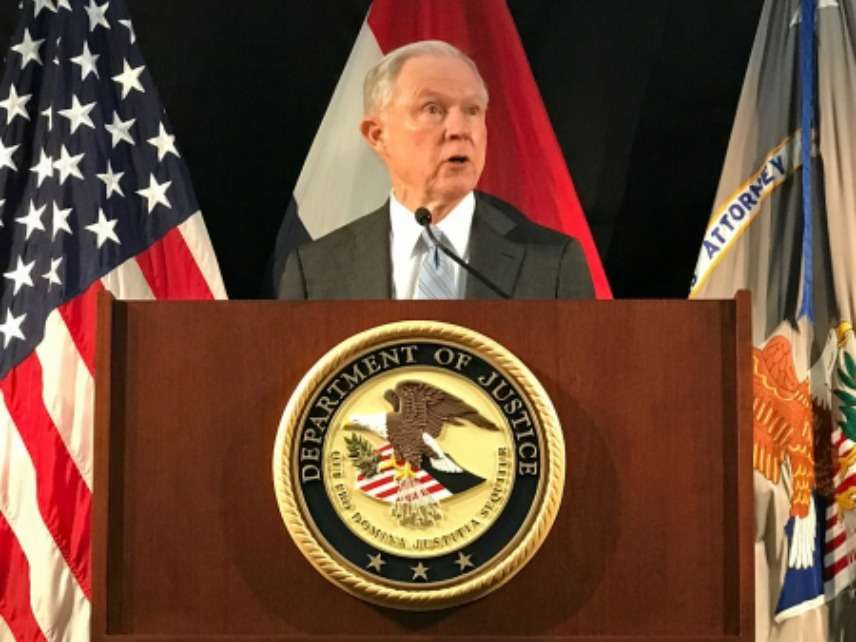

As Mike Riggs noted on Tuesday, Attorney General Jeff Sessions sent congressional leaders a letter urging them not to include the rider, which has to be reapproved each fiscal year, in the DOJ appropriations bill enacted last month.

After Congress rejected Sessions' request, President Trump signed the bill but issued a statement implying that he might ignore the rider if that was necessary to meet his "constitutional responsibility to take care that the laws be faithfully executed." Such a scenario is hard to imagine, since those laws include the restrictions imposed by the Rohrbacher/Farr amendment.

It's not clear how significant the letter and the signing statement are as indicators of Sessions' intentions because the Obama administration also opposed the Rohrabacher/Farr amendment and urged courts to read it narrowly. Under Eric Holder, the DOJ argued that the rider covered only direct legal challenges to medical marijuana programs. Last year the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit rejected that interpretation, ruling that the rider also prohibits the prosecution of people who supply or possess marijuana for medical use in compliance with state laws.

Despite opposing the rider, the Obama administration eventually settled on a policy of prosecutorial restraint, generally tolerating state-licensed marijuana businesses, including those serving recreational consumers, unless they violated state law or impinged on "federal law enforcement priorities."

Sessions has said he agrees with much of that policy but thinks it was not applied vigorously enough—an attitude that, along with his well-known anti-pot prejudices, could signal a crackdown. But so far Sessions has not tried to shut down state-legal cannabusinesses, which federal prosecutors could easily do simply by writing some threatening letters. Nor has he challenged state marijuana laws in federal court, even as lawsuits by other parties (neighboring states, local law enforcement officials, and anti-drug activists) have fizzled out.

Sessions' restraint may have something to do with positions taken by his boss before and after the presidential election. During the campaign, Trump repeatedly said states should be free to legalize marijuana, and he has consistently said medical use should be permitted. A crackdown on medical marijuana would break Trump's promises, and it would stir up a lot of political trouble with no obvious upside, other than gratification of Sessions' prohibitionist impulses.

Still, it would be nice to have some lasting protection from the attorney general's whims. In addition to prohibiting federal prosecution of patients and their suppliers, the CARERS Act would eliminate some obstacles to marijuana research, allow doctors employed by the Veterans Health Administration to recommend medical marijuana in states where it is legal, and remove cannabidiol, a nonpsychoactive but therapeutically promising component of marijuana, from Schedule I, the most restrictive category under the Controlled Substances Act. The bill, which was originally introduced in 2015, no longer includes provisions that would have removed marijuana from Schedule I and protected banks that serve the cannabis industry.

Those provisions were cut in the hope of attracting broader support for the bill. The initial sponsors this year include Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), who did not back the 2015 version, as well as Sens. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), Cory Booker (D-N.J.), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), and Al Franken (D-Minn.), who were cosponsors then.

Show Comments (22)