Why the World Health Organization is Wrong on Soda Taxes

WHO's proposal that countries enact steep fees globally is wrong and unjustified.

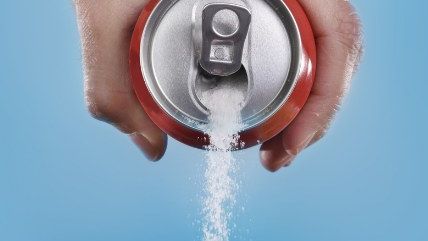

Earlier this week, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a report, "Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases," that suggests countries around the world should enact exorbitant taxes on soda—as high as 50 percent—"and other foods and beverages high in sugar, salt and fat" as a means of combating obesity and other diet-related diseases. The report also urges governments to adopt subsidies to make fruit and vegetables less expensive to purchase.

The WHO report suggests these subsidies and taxes can "create incentives for behaviours associated with improved health outcomes and discourage the consumption of less healthy options."

Similar, far smaller taxes are on the books in a growing number of local and international jurisdictions.

Berkeley, Calif. was the first U.S. city to pass such a tax. Philadelphia adopted a soda tax earlier this year, though that tax, a cash grab on the part of the city—and one for which the city's been sued by beverage makers and distributors—was intended to add to the city's coffers rather than to combat obesity. San Francisco, Boulder, Colo., and several other cities around the U.S. will vote on local soda taxes next month.

Globally, Mexico is one of several countries that has enacted a soda tax.

The regulatory momentum, it seems, is on the side of soda taxes. Why, though?

A Los Angeles Times piece this week on the new WHO report notes several popular and on-point critiques of soda taxes, including issues of "fairness (consumption taxes are a bigger burden for poor than rich people), freedom (the government shouldn't interfere with your personal choice of what to drink), trust (officials won't spend the tax revenue the way they say they will) and economics (small business will be harmed if taxes discourage sales)."

Earlier this year, in an April bulletin, the WHO seemed far less certain of the impact of soda taxes on obesity, arguing that "pricing policies can influence purchasing patterns and have an impact on dietary behaviour," without claiming that such taxes could or would lessen obesity rates. "Time will tell whether the tax helps to reduce obesity prevalence as well," the WHO wrote at the time, of Mexico's tax.

It could be a long time.

One of Mexico's chief soda tax proponents, Dr. Juan Rivera Dommarco, director of the Mexican Research Centre in Nutrition at the National Institute of Public Health, admitted that soda taxes—even if they work—won't be impacting eating habits or health anytime soon.

"The results in terms of a real reduction in obesity and increase in healthy consumption habits will not show immediately," he said.

A WHO expert, Dr. Gojka Roglic, WHO medical officer, said it could take "five years or more" for any potential changes in obesity rates to appear.

These less-than-impactful predictions about the impact of soda taxes on obesity occurred as data showed soda consumption in Mexico had fallen in the wake of the tax. But, as I wrote earlier this year, if soda consumption fell after Mexico's law took effect, it began to rise again shortly afterwards. That's not what a successful policy looks like.

What's more, while the new WHO report calls for "economic tools that are justified by evidence," the report admits there's "[l]imited evidence"—or what the report charitably characterizes as an "evidence gap"—that "target[ing] sugar-sweetened beverages" will impact non-communicable disease outcomes.

So just what did the WHO recommend, earlier this year, as an effective strategy to combat obesity? It wasn't soda taxes.

"WHO recommends other price policies such as subsidies for, or lower taxation of, healthy food as well as initiatives to encourage people to eat a healthier diet, avoid tobacco and be more physically active," the body wrote in its April bulletin.

The need to combat obesity using methods other than soda taxes echoes an independent 2014 report from McKinsey. That report, which notably used WHO methodologies, found that a tax on foods that are high in sugar or fat ranked near the bottom in terms of its cost-effectiveness and potential impact as a programmatic lever in the fight against obesity.

There's no doubt that obesity is a problem in the United States and elsewhere. It's one I don't claim to know how to solve. I've argued before that we should stop using taxpayer money to encourage the growth and production of sweeteners by eliminating farm subsidies and/or tariff protections for those who grow crops—particularly sugarcane, sugar beets, and corn—that are turned into those sweeteners. (While we're at it, I'd also eliminate all other farm subsidies and food-related tariffs.)

If that in turn makes sugar, soda, cookies, candy, energy drinks, and other sweetened foods and drinks more expensive, then consumers can choose to adjust their consumption habits accordingly, without having been taxed to support the production of those sweeteners in the first place.

We shouldn't be taxed to encourage farmers to grow crops that become sweeteners. And we shouldn't be taxed for consuming the foods we encouraged those farmers to grow, either. Unlike the WHO report, there's no "evidence gap" in that reasoning.

Show Comments (158)