Probation for Sex With Another Teenager, 3.5 Years in Prison for Failing to Register

The 9th Circuit upholds retroactive application of Arizona's registration requirement for sex offenders.

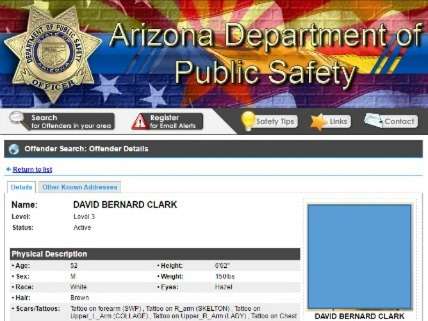

When he was 18, David Clark had sex with a 14-year-old. In 1982 he pleaded guilty to sexual misconduct, a Class 2 felony under Arizona law, and was sentenced to four years of probation. The following year, the state legislature passed a law that retroactively required Clark to register as a sex offender. In 2009 he was arrested for failing to register, a Class 4 felony. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison. Last week a federal appeals court said there was nothing constitutionally amiss about this series of events, because the law threatening to put Clark behind bars is not punitive.

Clark, who faces a much more severe penalty for failing to register than he did for his original offense, takes a different view, arguing that retroactive application of the registration requirement violates the Constitution's ban on ex post facto laws. Not so, said the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, because the Ex Post Facto Clause prohibits new punishments for old crimes, and forcing sex offenders to register is not a punishment; it is a regulation "intended to protect communities," and the burdens it imposes are not so punitive in effect that they override the legislature's regulatory intent. While sending Clark to prison may be a punishment, it's not for the crime he committed in 1982; it's for the one he began committing in 1983 by failing to register.

That logic is consistent with Smith v. Doe, the 2003 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Alaska's sex offender registry. While the indelible, life-disrupting stigma caused by inclusion in an online database of sex offenders may feel like punishment to the people on the list, the Court said, that effect is incidental to the registry's regulatory function, so a retroactive registration requirement does not violate the Ex Post Facto Clause.

Clark argues that Arizona's law has a bigger punitive impact than Alaska's did, because Internet use is more common now and because Arizona requires sex offenders to provide "online identifiers" (such as email addresses and social networking names), which facilitates harassment. A state appeals court thought those differences were not significant enough to distinguish Arizona's law under Smith. The Arizona Supreme Court declined to hear the case, and a federal judge, responding to Clark's habeas corpus petition, upheld the state appeals court's decision. So did the 9th Circuit, which decided "the Arizona Court of Appeals was not unreasonable in holding that the statute's punitive effects fail to outweigh its regulatory purposes."

By contrast, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit last month ruled that Michigan's Sex Offender Registration Act (SORA) went far enough beyond the Alaska law upheld by the Supreme Court that it qualified as punitive:

A regulatory regime that severely restricts where people can live, work, and "loiter," that categorizes them into tiers ostensibly corresponding to present dangerousness without any individualized assessment thereof, and that requires time-consuming and cumbersome in-person reporting, all supported by—at best—scant evidence that such restrictions serve the professed purpose of keeping Michigan communities safe, is something altogether different from and more troubling than Alaska's first-generation registry law. SORA brands registrants as moral lepers solely on the basis of a prior conviction. It consigns them to years, if not a lifetime, of existence on the margins, not only of society, but often, as the record in this case makes painfully evident, from their own families, with whom, due to school zone restrictions, they may not even live. It directly regulates where registrants may go in their daily lives and compels them to interrupt those lives with great frequency in order to appear in person before law enforcement to report even minor changes to their information.

Arizona's law shares some of these features. It bars people convicted of "a dangerous crime against children"—which includes "sexual conduct" with a 14-year-old, even when it is consensual and the offender is another teenager—from living within 1,000 feet of a school or child care facility. It assigns sex offenders to risk levels that exaggerate the danger they pose. Clark, for instance, is listed as a Level 3 offender, which is considered the most dangerous category, even though it's doubtful that someone who had sex with another teenager at age 18 posed a serious threat to public safety at the time, let alone 34 years later. Compounding that absurdity, Clark will remain in the registry for the rest of his life, suffering all the legal, social, and economic consequences of that status. He will have to keep the authorities apprised of changes in his information under threat of fines and jail, although Arizona's reporting requirements are not quite as demanding as Michigan's.

If Clark had been a year younger and his sexual partner had been a year older, he might have qualified for a "Romeo and Juliet" defense (under current law, at least). While the age of consent in Arizona is 18, a teenager younger than 19 can avoid criminal penalties if his partner is at least 15 and no more than two years younger. Life-derailing penalties should not hinge on such small differences, and the fact that Clark got probation indicates that the judge had some sense of proportion. Unfortunately for Clark, Arizona's registration law does not.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

it is a regulation "intended to protect communities," and the burdens it imposes are not so punitive in effect that they override the legislature's regulatory intent.

An argument so stupid, only someone supremely educated/a lawyer could make it.

If you call a dogs tail a leg, it's still a tail.

And forcing convicted criminals to be exposed in the pillory isn't a punishment, either.

/sarc

And if it's not a criminal punishment, then I suppose you can be put on the registry without having been convicted of a crime?

Am I missing something, or isn't that the logical consequence of their position?

Am I missing something, or isn't that the logical consequence of their position?

The intended, logical consequence of their position, yes.

Ever seen a copy of that Coppertone sunscreen ad from the '60s? You're gonna need to go on a registry.

The law is all about intentions and not effects.

Sweet! Thanks for the clarification, judges! Doin' a heck of a job.

9th circuit FTW!*

*Worst constitutional decisions contest.

"Not so, said the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, because the Ex Post Facto Clause prohibits new punishments for old crimes, and forcing sex offenders to register is not a punishment; it is a regulation 'intended to protect communities,'"

Oh come the fuck on. At least "fuck you, that's why" is honest.

When two sexually mature individuals have consensual sex, it is not pedophilia and there should be no implicit danger to elementary school kids.

This simple observation underscores the problems with current offender registry laws. They are not only ineffective at protecting the public, they obfuscate real dangers while making normal life impossible for many who have no desire to harm anyone.

You do understand that girls as young as nne or ten have "grass on the field"?

Unless they shaved it off...

You disgust me. That's saying children should be allowed to have sex with anyone else sexually mature, including 60 year old men. Would you like a train run on your so called sexually mature daughter by a bunch of 60 year olds?

One thing I don't quite get here, beyond that they have other goofy precedents to fall back on, is how the hell a regulation differs from a law when it comes to applying it after the fact. The principle for not applying rules retroactively is that you couldn't know the consequences of your behavior beforehand. This is the cornerstone of justice and it really has nothing to do with whether the rule in question is punitive or not, or a law or a regulation.

I often stop myself from even trying to make serious arguments at this point as so rarely do people even try to form intellectually honest/consistent positions.

+1 Penaltax

Penaltax uses retroactive punishment! Its super effective!

What is it gonna take for guys to stop fucking 14 year old girls?

According to Government Almighty, the stiffer the punishment, the more that "society is protected"...

So what it's a-gonna take is, all fuckers of 14-year-olds, are gonna hafta have their entire home city nuked till it glows!!!

He-hee, he said 'stiffer'. he he.

My first was 14, and I was 16. But, that was not the worst of my transgressions! I was more than lucky, considering my teenage sex drive. Too bad a cougar did not find me! I could have been well versed for the college girls

The other solution might be some sort of biochemistry or genetic engineering fix...

Make the 14-year-old babes look like 95-year-olds, and the 95-year-olds look like the 14-year-olds!

As Libertarians who oppose Government Almighty over-reach and over-kill, we should be working on this here fix I am cooking up here... Or maybe sexbots would be more attainable in the near term...

the 95-year-olds look like the 14-year-olds!

Lots of broken hips?

We have totally lost our minds about this stuff. I was flipping channels this weekend and one of these music channels had a show on about the old 80s band Berlin, who are apparently still around. During the show they talked about how Terri Nunn, the rather attractive lead singer for the band, was under a different name a Penthouse Pet of the month in 1977. No big news except that she was either 15 or 16 years old when she posed for the shots, depending on who you believe.

These pictures are still out there and all over the web. No one seems to be making any effort to take them down and certainly no one at Penthouse was ever prosecuted. Meanwhile, we are throwing kids into jail and marking them as sex perverts for life for the crime of sending a naked picture of themselves or receiving one.

It is not so much that we have bad standards or that I think legalizing 16 year old porn is a good idea. It is that we have no standards. Sometimes underage porn is the worst thing imaginable and should ruin the lives of everyone it touches. Other times it is just another footnote to the life of some pop singer right along with the fact that she auditioned to be Princess Lea. The entire thing is absurd.

John, you take my breath away.

She is 55 now and still looks pretty good. Back in the day, actually before they had any big hits, she was smoking hot.

I remember a night we walked along the Seine.

"I'm a man!"

Linky

flipping channels

Yeah, sure you were.

Dude. Euphemism, OK?

Damn you.

So, Netflix and chill by himself?

Heckuva euphemism there, Brownie!

How exactly would I be jerking off and discover that Nunn had been in Penthouse? That seems to be kind of an odd sequence of events.

Not for nothing, but Traci Lords is the centerfold for the biggest selling issue of Penthouse ever. The one with Vanessa Williams nude when she was still Miss America.

Anyone over 18 who masturbated to Traci lords is a sick pedophilic bastard.

Ex post facto is a thing. Or not.

Wait until they make defending hate crimes a hate crime and defending sex crimes a sex crime - all you damn perverts are going on a list.

defending hate crimes a hate crime and defending sex crimes a sex crime

I seem to recall something like that where defending people from charges that they gave material support to terrorism was itself giving material support to terrorism.

Damn you, Jacob Sullum. If having sex with a 14-year old is a crime, isn't thinking about having sex with a 14-year old wrong as well? And yet here you are writing a whole article with the clear intent of deliberately inciting people to think about the issue of having sex with a 14-year old. What's wrong with you that you would think that's okay?

thinking about having sex with a 14-year old wrong as well?

Hate crime = Lust Crime = Thought Crime.

Best part? They can keep you locked up until you stop having 'those' thoughts.

The 9th is the most reversed of the circuit courts isn't it?

Funny thing, when I was practicing medicine in rural area of the country, the mother of a 14 year old was outraged by the 24 year old, (who she was stupid enough to let live in her home) when he got her pregnant. The judge involved would not do a thing! No statutory rape charges! So, why would things like this be OK, but an 18 year old male gets such harsh treatment? He could have been 17 before contact. I remember, back in the '70-s that many 14 year old girls were having sex with pre-18 year old teens with no problems. It is, also, very possible that the young man involved started the relationship before he turned 18! No matter what, the sex offender laws need to be nationalized, and a standard made that all can agree upon. He did not deserve to have his life ruined for doing what the rest of his classmates were doing!

Yes, because "but everyone is doing it" is such a valid reason. That's the logic of children.

Cant do the time, dont do the crime.