Court Upholds the FCC's Politically Driven Decision to Regulate the Internet Like a Utility

The White House pushed the agency to reclassify internet service under Title II, and the agency complied.

A federal appeals court just gave its stamp of approval to the Federal Communications Commission's politically motivated decision to regulate the internet like an old-style utility. The ruling is a major victory for advocates of net neutrality, and in particular for the Obama administration, which pushed the FCC to pursue a heavy-handed regulatory scheme for the net.

The FCC's years-long quest to implement neutrality is a lengthy bureaucratic saga built on a back and forth between agency rule changes and court decisions. But at its core, it's a story about political pressure to expand the federal government's regulatory power over the internet.

Just over a year ago, the FCC voted to radically overhaul the way the internet is regulated, changing it from a lightly regulated information service under Title I of the Communications Act to a much more heavily regulated telecommunications service under Title II. Essentially, the FCC decided to regulate internet service providers (ISPs) as a utility, like legacy landline phone systems, under a regulatory model developed in 1934.

That move was designed to give the FCC the legal authority to implement strict rules around net neutrality, which would govern how ISP can manage and design traffic flow across their networks. The basic principle of net neutrality is that all internet traffic should be treated equally, which supporters argue is necessary in order to avoid internet fast lanes that discriminate against certain types of traffic.

But in practice what it ends up doing is limiting how internet companies can manage their networks, while giving the FCC a huge amount of discretionary authority over online innovation. Net neutrality rules typically have carve outs for "reasonable" network management, but what that inevitably is that the FCC ends up deciding what is and isn't reasonable on a case-by-case basis. So any time internet companies are planning to put in place new network functionality, they have to consider the possibility that the FCC will nix it as unreasonable.

It's effectively a system that requires ISPs to ask the FCC for permission to improve their networks. And the end result is that there's a chilling effect on ISP innovation , and that the FCC turns in a powerful chokepoint that has substantial, relatively unchecked power over what sorts of innovations are allowed.

Net neutrality has long been a priority some of the Obama administration's most active supporters, with groups like MoveOn pushing the issue, and in turn it has also been a priority for the administration. In 2008, Obama campaigned on implementing the policy, and during the president's first term, the agency attempted to implement net neutrality rules, with then-Chairman Julius Genachowski declaring that the agency "must be a smart cop on the beat preserving a free and open Internet." But the agency was repeatedly rebuked by the courts, which said that the FCC lacked statutory authority to regulate net neutrality.

That's where Title II comes in. The FCC has much more authority to regulate services under Title II than under Title I, and net neutrality advocates have long argued that the surest way for the FCC to claim authority to regulate net neutrality is through a wholesale shift in the way the agency classifies internet service.

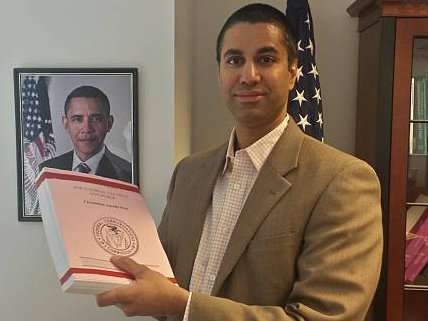

A number of FCC commissioners, however, maintained that a wholesale reclassification would cause a number of serious problems, and would require a legally fraught "forbearance" process, in which ISPs would be exempted from some parts of Title II that wouldn't or shouldn't apply. FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, who was appointed by President Obama, initially resisted the idea of Title II reclassification, and developed a proposal intended to implement net neutrality rules under Title I.

Then, in the fall of 2014, President Obama put out a statement explicitly urging the FCC to pursue the "strongest possible" net neutrality rules by reclassifying internet service under Title II. Shortly thereafter, Chairman Wheeler shifted his position too, proposing to go ahead with the reclassification process.

Now, Wheeler is, in theory, the head of an independent agency that is not subject to orders from the White House. Appearing before Congress, Wheeler denied receiving "secret instructions from the White House," and claimed that there had been no collusion between his agency and the administration regarding the Title II overhaul. Wheeler's sudden turnabout didn't make much sense, and neither did his stated reasons. He argued that wireless networks had thrived under Title II, for example, seeming to forget that they had been specifically exempted from Title II regulated.

But the timing of the shift was more than a little suspicious. And there were more than a few reasons to believe that the move had been driven by the White House's influence.

As The Wall Street Journal reported last year, the White House had engaged in an "unusual, secretive effort" to make the case for reclassification, with a pair of aides running a projected that "[acted] like a parallel version of the FCC itself" in what the aides believed would be a defining part of the president's legacy.

The White House's influence was further confirmed in March of this year, when a Senate Republicans released a report revealing internal FCC emails showing that agency staffers believed that President Obama's declaration of support for reclassification would affect the drafting of the new rules. One FCC staffer forwarded a news article about the president's announcement with the subject line, "Obama says to make it Title II." The FCC may not have been given a secret order, but staffers understood perfectly well what they were being told to do, and proceeded to do it.

So this is what the federal appeals court held up today: Not just the latest government plan to regulate the internet, but an unusual and politically motivated scheme to give federal regulators far more power over the internet, and, in the process, to give the White House far more influence over supposedly independent federal regulators. This will certainly be part of Obama's legacy—but not, I suspect, in a good way.