Eric Holder's Views on Sentencing Evolved More Slowly Than He Remembers

The former attorney general supported mandatory minimums for drug offenses as a federal prosecutor in the 1990s.

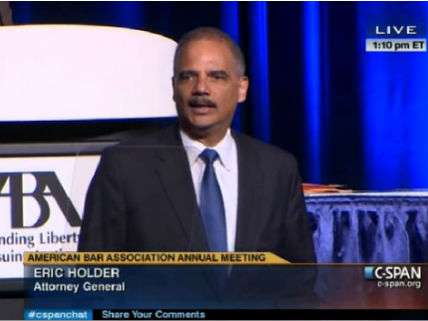

As I've said before, Eric Holder deserves credit for calling attention to excessively harsh criminal penaltes when he was attorney general. But in his recently aired interview with Frontline, his recollection of his growing misgivings about mandatory minimum sentences gives him more credit than he deserves. According to Holder, he recognized the injustice of harsh and rigid drug penalties when he was serving as a judge on the Superior Court of the District of Columbia in the late 1980s and early '90s. But he was still defending mandatory minimums for drug offenses as the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia in 1996.

Here is how Holder describes the evolution of his views on sentencing:

I experienced firsthand what it was like to be a judge, to send people to jail for inappropriate amounts of time given what they had done….

I'm a judge here in Washington, D.C. Somebody sells $20 worth of crack to an undercover police officer. Under the laws that existed in Washington, D.C., at that time, that would get you a five-year mandatory minimum sentence. Now, the person who might have sold those drugs was selling the drugs because he or she had received some drugs from a larger drug dealer to support their own habit, and the sale of that $20 rock would put that person in jail for five years, when what that person really needed was drug treatment.… Now, a sentence of five years for selling a $20 rock to an undercover police officer, when you're doing that to support a drug habit that you have, that just seemed to me to be not a good use of resources. But more than that, that just seemed to me fundamentally unfair.

If so, that conviction did not stop Holder from urging the D.C. Council to reinstate mandatory minimums for drug offenses in 1996, when he was the District's top federal prosecutor. According to The Washington Post, Holder also argued that the penalties for selling marijuana were "much too lax to address the problem." That same year, he told the Post "we have too long taken the view that what we would term to be minor crimes are not important," referring specifically to marijuana possession. "If you take these so-called minor crimes seriously and treat them fully, it has a ripple effect."

In 1997 Holder criticized jury nullification in cases involving nonviolent drug offenses: "While an isolated drug sale might be viewed as nonviolent, Holder said, the crack cocaine trade as a whole 'has had a devastating impact on the city, largely because of the violence associated with it.'" Never mind that the violence is an entirely predictable side effect of prohibition.

Holder began to publicly express doubts about drug sentences two years later, when he was deputy attorney general. At that point he conceded "there are some questions that we ought to ask" about "mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders." By the time he became attorney general in 2009, Holder favored equal treatment for the smoked and snorted forms of cocaine. Although Congress did not go that far, in 2010 it shrank the gap substantially. In 2013 Holder gave a widely noted speech declaring that "too many Americans go to too many prisons for far too long, and for no truly good law enforcement reason." He returned to that theme repeatedly and issued new charging guidelines aimed at reducing the number of drug offenders subject to mandatory minimums.

In the Frontline interview, Holder emphasizes the importance of passing sentencing reform legislation this year:

If this doesn't happen, this would be, I think, one of the worst moments in recent congressional history. I'd be ashamed of this nation if we didn't pass some significant new legislation….

Given the human cost that's paid under the schemes that are in place, given the number of people who are serving life sentences for nonviolent crimes, or who are serving 20- and 30-year sentences for nonviolent crimes, who have paid their debt to society and are still in jail, at some point it's incumbent upon people who hold levers of power to simply do the right thing. And the right thing here is clear. It's absolutely clear.

I agree. But it was not quite so clear to Holder as early as he implies.

Show Comments (26)