Justice Scalia Liked the Court. He Loved the Constitution.

Law students jokingly called him the pope of originalism, a phrase he loved.

When the sad news came of the sudden death this past weekend of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, I wept for my friend.

We had developed a happy friendship during the past 15 years, one which I had selfishly hoped would endure. He permitted his friends to see all of him. We knew him to be in private just as he appeared in public—happy, loud, brash, warm, engaging, challenging, witty, brilliant, courageous, Catholic, traditionalist. He also let us know that he understood the significant role history gave him. Knowing him personally and spending private time with him was one of the great gifts of my adult life. In my heart, there is a great sense of loss.

Regrettably, in the nation there is a sense of loss for the Constitution as well.

Justice Scalia was the most aggressive and consistent defender on the Supreme Court of the primacy of the text of the Constitution in the post-World War II era. He was the modern-day progenitor of the idea—and eventually the jurisprudence—of interpreting the Constitution faithful to the plain meaning of its words. He was utterly and unambiguously faithful to this concept. This theory of constitutional interpretation has two names—textualism and originalism.

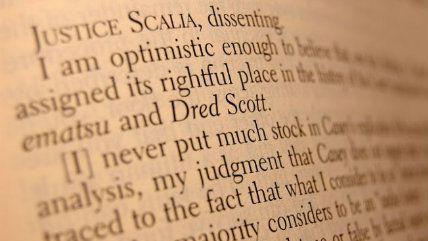

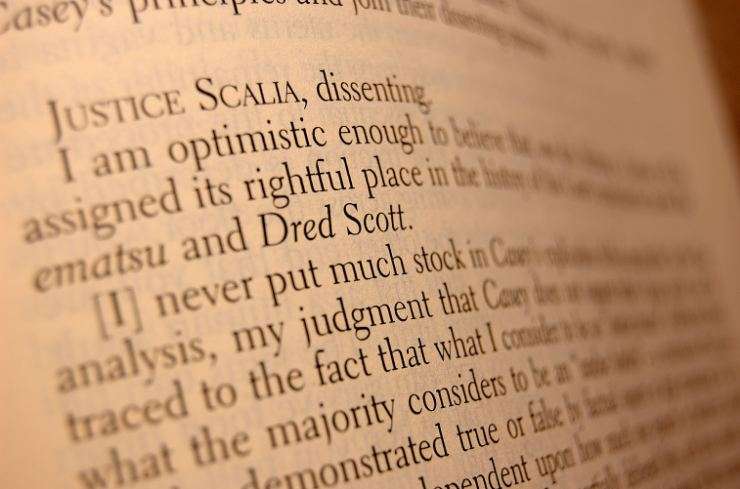

Justice Scalia argued that the Constitution means what it says; its says it is the supreme law of the land; and all American judges have taken an solemn oath to be subject to what it says. It is superior to the jurists who interpret it. It is what is says, not as they might wish it says. Thus, all judges are bound by the text. Hence the word "textualism."

So "no law" means no law. "Due process" guarantees fair process, not substance. A constitutional guarantee is a real guarantee. The exercise of rights articulated in the Constitution cannot be subject to popularity contests.

If the text of the Constitution is ambiguous, it then becomes the duty of the jurist to ascertain the original public meaning of the words that form the ambiguity. Hence the word "originalism." Ascertaining original public meaning often requires the skills of a historian; yet, thanks to James Madison, the historical record is ample.

The rejection of this line of thinking permits jurists to interpret the Constitution in novel and creative or even destructive ways, according to their own ideologies. It permits them to adapt a meaning in the text that they wish had been there to fortify contemporary societal attitudes. Justice Scalia argued that that is not the job of jurists.

Federal judges have life tenure because they represent the anti-democratic part of the federal government. Their job is to preserve constitutional norms and structures and guarantees from interference by the popular branches of the federal government or the States, even when those branches or the States command popular support.

The job of the jurist, he argued, is not to adapt the text of the Constitution to public trends or cultural changes. That is the job of the Congress and the States through legislation.

His textualism/originalism arguments provoked a firestorm of opposition on the Court and in the legal academy. The opposition reacted and coalesced around a concept called the "living Constitution." Its tenets are that modern-day jurists can adapt the Constitution to modern-day societal preferences and governmental needs.

Justice Scalia argued that that itself violates the judicial oath, which is to uphold the Constitution as it was written, not as some jurists may wish it to be. Only three quarters of the States, he maintained, can change the Constitution—by amendment—and they have done so only 27 times in the past 225 years.

Some justices throughout history have been compromisers and conciliators. Not Justice Scalia. He was a lion of textual orthodoxy. He was a rock of original meaning. Law students jokingly called him the pope of originalism, a phrase he loved.

This steadfast attitude about the proper judicial role on the Court led him to author staunch defenses of the right to life even in the womb, free speech even when hateful, private property even when it is in the government's way, the right to confront one's accusers at trial even when unpleasant, the right to keep and bear arms in the home even if locally prohibited, and the right to privacy in "persons, houses, papers, and effects."

He famously voted to limit privacy to those four areas because of his fidelity to the text of the Constitution, which articulates persons, houses, papers and effects as the areas immune from government intrusion without a proper search warrant. He believed that if those areas are to be expanded, it is for the States to expand them by amendment, not for the Court to do so based on a wish list.

In the early days of our friendship, I was a bit awed by him. I once asked him if he felt he belonged to the Court. His reply was short and blunt. He told me he belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, he belonged to his family, and he belonged to the Constitution. The Court, he said, was just one creature intended to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution. The Constitution is the Court's creator. No creature can be greater than its creator. He liked the Court. He loved the Constitution.

Now he is with the Creator of us all. Now he belongs to the ages.

COPYRIGHT 2016 ANDREW P. NAPOLITANO | DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM

Show Comments (39)