Bernie Sanders Promises to Reduce Prison Population, Misses the Simple Solution of Not Messing With People

Acknowledging the role of the democratic will of the people and democratically-enacted laws in problems with policing would require taking responsibility.

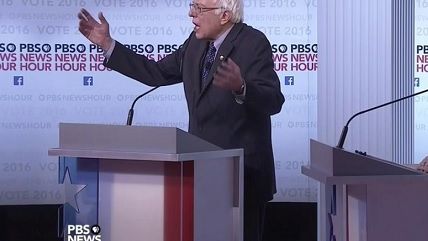

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) promised at tonight's debate that by the end of his first term he would reduce the U.S. prison population so it was no longer the largest in the world. The promise came during an extended "discussion" of criminal justice reform that was long on identify the problems in the criminal justice system but short on either identifying the causes of the problems or the solutions.

"Today a male African-American baby born today stands a one-in-four chance of ending up in jail. That is beyond unspeakable," Sanders said—there was a lot of talk about race at the top of this, the last debate before the South Carolina primary. "So what we have to do is the radical reform of a broken criminal justice system."

But Sanders didn't really offer any "radical reforms." He said over-policing in African-American neighborhoods had to end and that there was too much racial disparities in traffic stops, drug arrests, and sentencing. He said the U.S. needed "fundamental police reform" but didn't identify what it was. Sanders has previously pointed to police departments as an example of "socialist institutions." When he ran for mayor of Burlington in 1981, Sanders was supported by the city's police union. He voted for the Clinton 1994 crime bill.

While "radical reforms" are all well and good, they're not necessary to alleviate some of the worst problems in the criminal justice system. Rolling back the laws that create all the opportunities for police to harass otherwise peaceable residents, especially those from marginalized communities, would go a long way in reducing the harm caused by the criminal justice system. Brian Doherty has explored this in detail, explaining how petty law enforcement traps the poor in a vicious cycle of escalating fines, warrants, and jail time.

When a series of incidents of police violence in New York City—including the death of Eric Garner, who was accused by cops of selling loose untaxed cigarettes—received media attention in the summer of 2014, Mayor Bill De Blasio (D), hailed as a progressive hero after his election, refused to even consider scaling back the kind of petty laws that lead to violent police interactions. Instead, he stood by as the police commissioner explained that submitting to police and complying with their orders by correcting your behavior for them was what "democracy" was all about. Last year, when police in New York stopped making "unnecessary arrests" and unnecessary traffic stops (like the ones Sanders complained about being racially disparate), de-escalating petty law enforcement in all communities, The New York Times argued such a withdrawal in minority communities constituted a civil rights violation.

The left has consistently avoided taking its share of responsibility for the endemic problem of police violence. Laws about drugs, guns, and other essentially non-violent behavior are pushed by nanny statists. Bernie Sanders may be wrong that police departments are socialist institutions, but they are democratic institutions. While racism is a problem, among police and everywhere else, police act to impose democratically-enacted laws on people.

Force is necessary whenever someone who believes they are free refuses to comply with a law that doesn't involve actual crime prevention. Reducing police violence will require reducing the opportunities for police to interact with peaceful residents. That, in turn, will require acknowledging that the laws we wish to impose on society involve violence when they're imposed on the individual level, something Bernie Sanders, for all his rhetoric, continues to miss.

Show Comments (80)