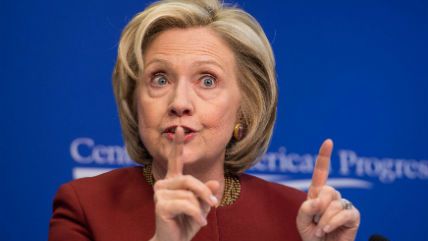

Hail to the Censor!

Hillary Clinton's long war on free speech

On December 6, after delivering an address about Israeli-American relations at the Brookings Institution's Saban Forum, Democratic presidential frontrunner Hillary Clinton was asked how she would deal simultaneously with the bloody dictatorship of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the terrorist menace of ISIS. After spending three minutes talking about Sunni insurgents and diplomacy with Russia, Clinton pivoted to a solution she has proposed for several disparate policy challenges across her decades in public life: censorship.

"We're going to have to have more support from our friends in the technology world to deny online space," Clinton warned, citing the deadly terrorist attack in San Bernardino four days earlier by a U.S.-born Muslim and his Pakistani wife. "Just as we have to destroy their would-be caliphate, we have to deny them online space."

But doesn't that go against the American cultural and constitutional tradition of free speech? Clinton anticipated the argument: "You're going to hear all of the usual complaints—you know, 'freedom of speech,' etc.," she said. "But if we truly are in a war against terrorism and we are truly looking for ways to shut off their funding, shut off the flow of foreign fighters, then we've got to shut off their means of communicating."

This was no heat-of-the-moment hyperbole. Earlier that same day, the former secretary of state was even more explicit about what she would demand from American technology companies: "We're going to need help from Facebook and from YouTube and from Twitter," she declared on ABC's This Week, announcing a strategy of fighting terrorists "in the air," "on the ground," and "on the Internet." "They cannot permit the recruitment and the actual direction of attacks or the celebration of violence. They're going to have to help us take down these announcements and these appeals."

You would think that a leading presidential candidate rolling her eyes at "freedom of speech" while advocating content-based takedown orders for U.S. media companies might generate a news cycle or two worth of raised eyebrows. But Clinton's illiberal proposals were drowned out within hours by the furor over Republican frontrunner Donald Trump calling for a "total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States." (Not to be outflanked on tech-toughness, the populist mogul also proposed "closing that Internet up in some ways," and scoffed even harder at potential critics: "Somebody will say, 'Oh, freedom of speech, freedom of speech.' These are foolish people.")

But long before Donald Trump became a one-man media-distraction machine, Hillary Clinton had mastered the art of pushing maximally against free expression without being tagged as a foe of the First Amendment, unlike her friend and anti-media collaborator Tipper Gore. Clinton has crusaded against not just "gangsta" rap (the scare quotes are hers), but also the "poison" spread by movies, television, and video games. Her record includes not just Gore-like Capitol Hill condemnations of content and agitation for parental warning labels, but also unconstitutional legislation mandating federal punishment for those who sell and market controversial entertainment.

She has consistently backed government intrusions into communications devices, from content-filtering V-chips on television sets to anti-encryption back doors on iPhones. She has established as her litmus test for Supreme Court nominees a commitment to overturn 2010's Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, in which a 5–4 majority overturned on grounds that "the censorship we now confront is vast in its reach" a federally enforced cable TV ban of a documentary film attacking a certain politician named Hillary Rodham Clinton. Several other laws that Clinton championed, including the Communications Decency Act (CDA) and the Child Online Protection Act (COPA), were opposed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and struck down by the Supreme Court as violations of the First Amendment. And she has grasped the flimsiest reeds of evidence to lay at least partial blame on artistic expression for everything from playground fighting styles to the Columbine massacre to, most infamously, the murder of four U.S. personnel in Libya.

How has Clinton preserved a solid reputation among creative professionals despite such a shaky record on speech? Largely because the industries in her critical crosshairs—Hollywood, Silicon Valley, gaming—lean overwhelmingly Democratic, and Democrats care more about defeating Republicans and defending core progressive issues than having to fend off sporadic state meddling into their workplaces. On November 19, the same day the technology-policy website Techdirt complained in a headline that "Hillary Clinton Joins The 'Make Silicon Valley Break Encryption' Bandwagon," The Washington Post reported that the presidential candidate's two biggest sources of campaign cash thus far were the technology and communications industries. And Clinton's biggest donor over the years? Haim Saban (after whom the Brookings forum at the beginning of this article is named), an Israeli-American rock musician who made his first billion from co-creating Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, a children's series that the then–first lady lambasted in 1996 as "one of the most violent television programs on television today."

The political press, which itself leans heavily left of center, often glosses over Clinton's more controversial free speech remarks and initiatives in favor of focusing on the political context in which they're made. During her October 2015 testimony in front of the House Select Committee on Benghazi, for example, she issued the remarkable claim that the murdered cartoonists of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo "sparked" their own assassinations by drawing caricatures of Mohammed—the free expression equivalent of blaming rape victims for wearing short skirts. Yet the ensuing news coverage was almost all about how the presidential contender stoically parried gotchas from a hostile GOP. "Hillary's Best Week Yet," ran the next-day headline in Politico. "The once-beleaguered candidate looks like a frontrunner again."

Clinton's wary approach toward free speech is based on three long-held beliefs, each of them highly contestable. The first is that media consumers, especially children, are hapless vessels into which manipulators pump propaganda, thereby dictating behavior. As she asserted to public radio broadcaster Diane Rehm in 1996, "The media, more than any other single institution in our society, has affected how children are raised and how they see themselves and what they think of their futures." The second is a lack of faith that the marketplace, in the absence of government pressure, is capable of solving, or even rendering obsolete, the problems she finds so vexing. The third is that the government itself can find—or order the private sector to develop—magic-bullet solutions to complex technical challenges. At the December 19 Democratic presidential debate, for example, Clinton called for a "Manhattan-like project" to give law enforcement the ability to penetrate encryption, two decades after her husband's very similar effort to mandate an encryption-defeating Clipper Chip in electronic devices was revealed to be (in the recent words of one of its designers) "an expensive, embarrassing fiasco."

Online bettors continue to treat Hillary Clinton as the overwhelming favorite to win the presidency; she's at 56 percent to Donald Trump's 16 percent as of late December, according to PredictIt. At a time when 51 percent of college students favor speech codes (according to an October Yale poll) and when noted law professors such as Eric Posner are writing columns with headlines like "ISIS Gives Us No Choice but to Consider Limits on Speech," it's worth examining how someone with Clinton's long and worrying track record might impact the legal and cultural climate for American free expression if elected to run the executive branch of the United States government.

'If I Could Do One Thing to Help Children in Our Country, It Would Be to Change What They See in the Media'

The most famous anti-Hollywood moment at a major-party political convention was Pat Buchanan's tub-thumping "Cultural War" speech of 1992, in which the Republican runner-up criticized among many other modern ailments "the raw sewage of pornography that pollutes our popular culture" and posited that "Clinton and Clinton are on the other side" of this fundamental divide. What's much less remembered is that Hillary Clinton herself slammed the entertainment industry in not one but two Democratic National Convention addresses.

"Right now there are parents questioning a popular culture that glamorizes sex and violence, smoking and drinking, and teaches children that the logos on their clothes are more valued than the generosity in their hearts," Clinton lamented in 1996. "I've listened to parents distressed about a culture that too often glorifies violence," she reiterated in 2000. "Why can't all of us—including the media—give parents more control over what their children see on TV, the movies, the Internet, and video games?"

For Clinton, parental "control" has translated into four types of policy initiatives: federal penalties (including, at times, prison sentences) for those who broadcast, sell, or market racy content to minors; mandates on communications equipment manufacturers; government-patrolled ratings systems; and requirements on broadcasters to produce more children's programming under threat of fines or license non-renewal.

The Clinton administration's first of many forays into the nexus between the entertainment industry and children came almost immediately after inauguration. "Broadcasters, beware," warned House Communications and Technology Subcommittee Chairman Ed Markey (D–Mass.), at a March 1993 hearing about the television industry's compliance with Federal Communications Commission (FCC) rules on children's programming. "The new era has begun. Standards are no longer going to be determined under…Reagan-Bush FCC standards…but rather the Clinton-Gore standards. There will be license challenges."

There were indeed license challenges and assorted fines levied on stations that were determined by the Clinton FCC to be insufficiently compliant with the 1990 Children's Television Act (CTA), a law that mandated minimum amounts of educational programming while limiting advertising during blocks aimed at young audiences. Immediately prior to Markey's hearings, leading CTA proponent and longtime media activist Peggy Charren "met with First Lady Hillary Clinton and won the Administration's tacit support for stronger enforcement of the law," according to a contemporaneous account in the Los Angeles Times. On the CTA's 15th anniversary, then-Sen. Clinton said in a statement, "I was proud to host the first White House Children's Television Summit and to help pass this landmark legislation."

The Children's Television Act was premised on the notion that "educational television programming for children is aired too infrequently," and that as a partial result, "children in the United States are lagging behind those in other countries in fundamental intellectual skills." In the year it was passed, the average U.S. household could access 33 television channels, according to Nielsen Media Research. By the time the law was strengthened for a third time in 2006 (Hillary Clinton had successfully barnstormed for a second ratchet in 1996 as well), the average number of stations was 104; now it's at 189. ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox, WB, UPN and PBS all have "kids" channels these days; Disney and Nickelodeon operate whole chunks of the dial; and you can watch educational programming everywhere from Discovery to Qubo to ESPN. Meanwhile, three of the five most popular YouTube channels worldwide in November 2015 were aimed at children.

The proliferation of child-friendly marketplace programming did nothing to dull Hillary Clinton's ire against broadcasters and other agents of commercialized crassness. To the contrary, the topic dominated her public focus after the twin 1994 defeats of Hillarycare and Democrats in the midterm elections. In a withering June 1995 commencement speech at Brooklyn College, for example, the first lady combined right-wing-style critiques of morality with left-wing rants about the market.

"Just look around and you will see the effects of what one political scientist has called 'turbo-charged capitalism,'" she railed. "Consumerism and materialism go unchecked, run rampant through our culture, dictating our tastes and desires, our values and dreams. We are fed, through the media, a daily diet of sex and violence and social dysfunction and unrealizable fantasies. We live too often in a disposable, throw-away society, where the yearning for profits and instant gratification overshadows the need for moderation and restraint and investing for the long-term."

That fall, both Clintons went ballistic at a Calvin Klein billboard campaign in which young-looking models (they were all at least 18) lounged about semi-suggestively in a wood-paneled basement. The ads were "merely the latest proof that some businesses are willing to push the envelope of gratuitous sex and exploitation of children as far as possible if it's good for the bottom line," Hillary snarled in her syndicated column, as the Department of Justice prepared an investigation that would eventually turn up zero wrongdoing. "The pervasive influence of exploitative advertising touches every aspect of our lives…Today, it's as if our society is a highway full of car wrecks. Only worse."

The outrage reached full throat with Clinton's bestselling 1996 book It Takes a Village: And Other Lessons Children Teach Us, which preceded a series of West Wing browbeating sessions that year with television executives. "I cannot stress too much," the first lady said while promoting the book on WAMU Radio in January 1996, "that if I could do one thing to help children in our country, it would be to change what they see in the media, day in and day out."

The "Seeing Is Believing" chapter in It Takes a Village is an open-handed slap to what remains of the progressive conceit about lefties championing transgressive cultural expression in defiance of puritanical scolds. In it, Clinton praises Tipper Gore's "courage" in pushing for warning labels on records, hails the virtues-polemicist William Bennett for successfully pressuring Time Warner to sell off Interscope Records because of the "offensive lyrics" found in that company's "'gangsta' rap," accuses broadcasters of "hiding behind the First Amendment," and blames TV news in part for the fact that "many children grow up skeptical that organized religion can offer guidance and sustenance" because all that negative programming "undermines their faith in institutions."

Above all, Clinton makes the repeated assertion that we just know children are being materially damaged by television. "Whether, and under what circumstances, the violence people see on television and at the movies actually incites violent acts is a question researchers have debated for years," she writes, in a typical passage. "As with smoking and lung cancer, however, we know that there is a connection."

We actually knew no such thing in 1996, and know something closer to the opposite two decades later. Researchers have indeed demonstrated what our own eyes tell us: that movies and television and video games have gotten considerably more violent over the years. Yet during the past two decades, during which the video game industry—which Clinton shifted her attention to in 1999—went from marginal to ubiquitous, the violent crime rate in the United States, including by juveniles, has been cut in half. As the Villanova psychologist Patrick Markey and his colleagues concluded in an October 2014 study comparing the consumption of cinematic mayhem to the perpetration of the real-world stuff since 1960, "Contrary to the notion that trends in violent films are linked to violent behavior, no evidence was found to suggest this medium was a major (or minor) contributing cause of violence in the United States."

The academic literature about video games and violence is more contested. Roughly, researchers largely agreed with Clinton before much evidence was in; now there's a fiercely polarized debate. But where more cautious politicians might be circumspect as the science works itself out, Hillary Clinton was and continues to be emboldened by certainty in how children absorb media. "They take those messages to heart like…little VCRs, and they play back what they have learned," she asserted in a 1996 speech to the Parent-Teacher Association. Nine years later, at a Kaiser Family Foundation speech, the song remained the same: "The body of data has grown and grown and it leads to an unambiguous and virtually unanimous conclusion: Media violence contributes to anxiety, desensitization, and increased aggression among children."

'This Bill Is…Not an Attack on Free and Creative Expression'

The book tour for It Takes a Village served as a rolling promotional campaign for the Clinton administration's signature entertainment-content legislation—the Communications Decency Act of 1996. The law, part of a broader Telecommunications Act, mandated that every television sold in America with a screen 13 inches or larger come pre-installed with a "V-chip," a programmable device allowing parents to screen out objectionable content as determined by a "voluntary" ratings system that the television industry would be encouraged heavily to adopt. "I believe that these past few months have marked a hopeful turning point for families and their relationships to those TV sets in their homes," the first lady crowed four months after her husband signed the Telecommunications Act into law.

The most controversial part of the CDA was a provision mandating punishment of up to two years in prison and $250,000 in fines for anyone caught publishing "patently offensive" material on the Internet where minors could access it. The ACLU immediately challenged this section on First Amendment grounds, and in June 1997 the Supreme Court agreed by a 7–2 vote.

"Under the CDA, a parent allowing her 17-year-old to use the family computer to obtain information on the Internet that she, in her parental judgment, deems appropriate could face a lengthy prison term," Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for the majority in Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union. "In order to deny minors access to potentially harmful speech, the CDA effectively suppresses a large amount of speech that adults have a constitutional right to receive and to address to one another. That burden on adult speech is unacceptable."

In response to that ruling, Hillary Clinton promoted, lawmakers passed, and Bill Clinton signed the Child Online Protection Act of 1998, which made the online selling or transferring of "material that is harmful to minors" (as determined by "community standards") punishable by up to six months in prison. The law was almost immediately tied up in the court system, with a 5–4 Supreme Court majority in 2004's Ashcroft v. the American Civil Liberties Union warning that "content-based prohibitions, enforced by severe criminal penalties, have the constant potential to be a repressive force in the lives and thoughts of a free people." SCOTUS killed the law once and for all in 2009.

In April 1999, while COPA was still tied up by an injunction, Hillary Clinton kicked off her first Senate campaign by calling for still more government intervention into media after teenagers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold slaughtered 13 people at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado.

"We can no longer shut our eyes to the impact that the media is having on all of our children, and on the potentially violent impact it is having on some," Clinton said during a Niagara Falls speech, as the national media was leaping to the conclusion—later demonstrated to be false—that the killers plotted their attack using violent video games. While hailing the administration's work on the V-chip and online porn, the candidate concluded that the rise of gaming and the Internet had made the screen-based universe too unwieldy to regulate with existing rules. "The problem of course is, as anyone will quickly recognize, that there is so much of it, we are awash in it….We are going to have to do some serious thinking in our country about how we will take more control over what our children see, and what they experience, and how they understand what they see and experience."

As a freshman senator, Clinton wasted little time in following the unconstitutional blueprint of the CDA and COPA, usually with the help of her friend Sen. Joseph Lieberman (I–Conn.), of whom she said at the 2000 Democratic National Convention: "I admire Joe's work to reduce the violence in our media." In May 2001, Clinton and Lieberman co-sponsored the Media Marketing Accountability Act, which would have imposed federal fines of up to $11,000 per day for "the targeted marketing to minors of adult-rated media."

Since the ratings guidelines that determined what is and isn't "adult" were still voluntary (though the act also called for the Federal Trade Commission to create its own system, in order to simplify what Clinton decried as the "alphabet soup" of different industries' self-evaluations), the law would have discouraged producers and distributors from having ratings in the first place, since only then would they expose themselves to the risk of federal sanction. As the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service concluded in an unusually opinionated June 2001 analysis, "The bill could impose a possible financial burden on speech, and that, as well as outright censorship, may violate the First Amendment."

Unsurprisingly, the entertainment industry balked. Recording Industry Association of America General Counsel Cary Sherman warned that the legislation "raises serious constitutional red flags." Motion Picture Association of America CEO Jack Valenti called it "a death sentence bill for voluntary film ratings." A defiant Clinton warned Hollywood that it had better stick to its rating system, or else. "If there is a move on the part of anyone to discard this kind of voluntary labeling or to turn their backs on this because finally we're feeling compelled to put some teeth into the enforcement," she told CNN, "I think we'd have to take a hard look at that." She never got the chance: The Media Marketing Accountability Act died in committee.

But Clinton and Lieberman were just getting started. In 2005, the duo teamed up with socially conservative Sens. Rick Santorum (R–Pa.) and Sam Brownback (R–Kan.) to introduce the Children and Media Research Advancement (CAMRA) Act, creating a $90 million federal research program to study the impact of media on childhood violence, obesity, and intellectual development. "I think it is as important a public health issue as any we can worry about with our children," Clinton told the Kaiser Family Foundation the week she introduced the bill.

That Kaiser speech was filled with unwitting admissions of her own futility ("Bill and I tried to implement some strategies, some rules, some regulations, but it wasn't quite as difficult 25 years ago as it is today….You know, no longer is something like the V-chip the 'one stop shop' to protect kids"). It also characterized childhood media exposure as a "silent epidemic," analogizing it to the deadly SARS virus.

"You know, if you hear that there is a child with an infectious disease in your school, you're going to be worried, and you might not send your child to school, and you're going to call and make sure that this child with the infectious disease has been properly treated and can't be contagious," she said. "Well, in effect, if you think of this from a public health perspective, you know, what we are doing today, exposing our children to so much of this unchecked media, is a kind of contagion. We are conducting an experiment on this generation of children and we have no idea what the outcomes are going to be."

Despite the many censorious implications in the bill and accompanying public relations campaign (including that a uniform ratings system be imposed and then "shown throughout every program or at least after every commercial break"), Clinton's latest bipartisan anti-media initiative was interpreted widely by the national press not as an alarming encroachment on speech, but as a canny political gambit. "What's Hillary up to?" asked Eleanor Clift of Newsweek. "She's laying the groundwork for a presidential run in '08, and she's paying attention to the voters." That groundwork failed on both counts: CAMRA passed the Senate but got nowhere in the House.

Undeterred, Clinton and Lieberman marched on with something much bigger: the Family Entertainment Protection Act (FEPA), making it a federal crime punishable by a $1,000 fine or 100 hours of community service to sell video games rated "mature" or "adults only" to anyone under 17. (Subsequent convictions would tack on $5,000 or 500 hours of service.) The act also tasked the Federal Trade Commission with evaluating the gaming industry's voluntary rating system, conducting annual secret audits of retailers, and hunting down hidden game content, such as the then-controversial sex sequence embedded deep into Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas. "This is a terrible problem that needs to be fixed," Clinton said when introducing FEPA on the Senate floor in December 2005. "And this bill does just that."

Perhaps stung at this point by the serial constitutional objections to her prior go-rounds against content providers, Clinton's introductory speech was downright defensive. "I want to be clear—this bill is not an attack on video games," she insisted. "This bill is also not an attack on free and creative expression. Relying on the growing body of scientific evidence that demonstrates a causal link between exposure to these games and antisocial behavior in our children, this bill was carefully drafted to pass constitutional strict scrutiny."

Each of Clinton's assertions was subsequently rejected in a series of court decisions, culminating in the Supreme Court's 7–2 ruling in 2011's Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, which overturned a California video game law that Clinton and company had used in crafting FEPA. The state, wrote Justice Antonin Scalia in his majority opinion, "cannot show a direct causal link between violent video games and harm to minors." As a result: "The Act does not comport with the First Amendment."

Clinton's two-decade-old theory about media consumers being unwitting vessels for malevolent actors had now been rejected at virtually every judicial level. FEPA was a nonstarter even before all that, failing to reach the Senate floor. But policy is not made by legislation alone, as the first lady–turned senator would soon demonstrate as secretary of state.

'We Are Going to Have the Filmmaker Arrested Who Was Responsible for the Death of [Your] Son.'

Before Benghazi, Secretary of State Clinton's record on Internet freedom and global free speech actually received positive marks from openness advocates. At a January 2010 speech at the Newseum, she made a strong case against international censorship. "The Internet is a network that magnifies the power and potential of all others," she said. "And that's why we believe it's critical that its users are assured certain basic freedoms. Freedom of expression is first among them."

But even in this, the arguable high-water mark of Clinton's free speech record, her doubts about expression bubbled constantly to the surface. "The same networks that help organize movements for freedom also enable Al Qaeda to spew hatred and incite violence against the innocent," she warned in one passage. And then: "Now, all societies recognize that free expression has its limits. We do not tolerate those who incite others to violence, such as the agents of Al Qaeda who are, at this moment, using the Internet to promote the mass murder of innocent people across the world. And hate speech that targets individuals on the basis of their race, religion, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation is reprehensible. It is an unfortunate fact that these issues are both growing challenges that the international community must confront together. And we must also grapple with the issue of anonymous speech."

So given this wariness and long track record, it shouldn't have been surprising that when angry mobs gathered outside U.S. diplomatic posts throughout the Muslim world on September 11, 2012, the department run by Hillary Clinton pre-emptively pointed the finger at a violent video—in this case an amateurish piece of YouTube cinema made by a dodgy resident of Cerritos, California, named Nakoula Basseley Nakoula.

"U.S. Embassy Condemns Religious Incitement," ran the headline atop a statement released that morning from besieged diplomatic personnel. It alluded to but did not mention Nakoula's July 2012 trailer for an anti-Islam fantasy titled Innocence of Muslims, of which a two-minute clip (with Arabic dubbing) had been broadcast and denounced on the Egyptian TV station Al-Nas by an Islamist pundit on September 8. "The Embassy of the United States in Cairo condemns the continuing efforts by misguided individuals to hurt the religious feelings of Muslims….We firmly reject the actions by those who abuse the universal right of free speech to hurt the religious beliefs of others."

"Incitement" in American free speech jurisprudence has a specific legal meaning, and this isn't it. According to the Supreme Court, speech can only be found to incite people when it is both intended and likely to produce "imminent lawless action." In the case of Cairo, it turned out there was imminent lawless action, in the form of a mob ransacking the U.S. embassy just hours after this unsuccessfully prophylactic press release, but the person who incited the mob was someone on the ground who said, "Let's attack the compound," not some would-be polemical filmmaker 7,500 miles away.

Amazingly, the diplomats kept playing film critic even after their embassy walls were breached. "This morning's condemnation (issued before protests began) still stands," the official embassy account tweeted, in a post that was later taken down. Though Clinton's State Department quickly distanced itself from its embattled employees ("The statement by Embassy Cairo was not cleared by Washington and does not reflect the views of the United States government," an unnamed administration official soon said), the secretary herself began a wobbly rhetorical balance that continues to this day: singling out Innocence of Muslims for condemnation, pointing out that it offers no excuse for the violence that threatened diplomatic posts in nearly a dozen countries, and yet blaming it in part for the deadly pre-planned attacks in Benghazi, Libya.

"The United States deplores any intentional effort to denigrate the religious beliefs of others," Clinton said in a September 11 statement. "Our commitment to religious tolerance goes back to the very beginning of our nation. But let me be clear: There is never any justification for violent acts of this kind."

In the Supreme Court's First Amendment case law, there is a concept known as the "heckler's veto"—the unconstitutional government suppression of speech out of concern over possible reaction to it. In 1969's Tinker v. Des Moines, the Court rejected the notion that fear of disruption was sufficient to bar high school students from wearing black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War.

In the private sphere, "heckler's veto" is used more casually to characterize acts that shut down others' expression (as in a heckler disrupting a speech) or acts of pre-emptive self-censorship made in deference to the heckler's beliefs or threats. When the overwhelming majority of American newspapers refused to reprint images from Danish anti-Mohammed cartoons that were used to justify violence that ended up killing more than 200 people worldwide in 2006, free speech advocates argued that the hecklers had won by getting non-Muslim publications to agree not only with their censorious ends, but with their overall critique that the images were offensive. There is a strategic component to the behavior of both parties; in the words of University of California, Los Angeles First Amendment scholar Eugene Volokh, "Behavior that gets rewarded gets repeated."

In the days after September 11, 2012, Hillary Clinton effectively rewarded the Islamists' bad behavior by emphasizing the U.S. government's agreement with their artistic critique. And the Obama administration skirted within shouting distance of the Supreme Court definition of a heckler's veto on September 12, when it asked YouTube to check whether the Innocence of Muslims trailer violated that company's rules against "hate speech" and should therefore be taken down. Google, which owns YouTube, kept the trailer up in the U.S., though it did censor the video in Egypt and Libya. Recently uncovered emails show Clinton's State Department communicating with Google on September 27 to make sure a "block" on an unnamed video remained in place until October 1.

On September 13, Clinton drew a direct link between the art and the violence: "I…want to take a moment to address the video circulating on the Internet that has led to these protests in a number of countries," she said. "Let me state very clearly—and I hope it is obvious—that the United States government had absolutely nothing to do with this video. We absolutely reject its content and message….To us, to me personally, this video is disgusting and reprehensible. It appears to have a deeply cynical purpose: to denigrate a great religion and to provoke rage." The State Department spent $70,000 broadcasting an edit of this message (spliced with similar sentiments from President Barack Obama) in Pakistan. And Obama singled out Innocence of Muslims for criticism in a September 25 address to the United Nations: "I believe its message must be rejected by all who respect our common humanity," he said. "The future must not belong to those who slander the prophet of Islam."

To this day, Clinton rejects the notion that extravagantly denouncing the video only encourages the next potentially murderous act against Western free speech. In fact, she believes her art criticism saved lives. "We had protests…all the way to Indonesia," she told Congress in October. "Thankfully, no Americans were killed, partly because I had been consistent in speaking out about that video from the very first day when we knew it had sparked the attack on our embassy in Cairo."

The word sparked is crucial here. American ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice famously used it while making the rounds on the Sunday morning talk shows on September 16—"What sparked the recent violence was the airing on the Internet of a very hateful, very offensive video that has offended very many people around the world." Clinton used it in front of Congress to describe the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks, as a way of defending her continued emphasis on Innocence of Muslims as a partial explanation for Benghazi. "I think it's important that we look at the totality of what was going on. It's like that terrible incident that happened in Paris…[in which] cartoons sparked two Al Qaeda–trained attackers who killed…nearly a dozen people."

But the metaphor is wrong in important respects that have implications for both speech and foreign policy. Innocence of Muslims, like the Danish cartoons before it, hung around unnoticed for months until they were picked up and spread around by Islamists looking to gin up outrage. These pieces of expression, in other words, were kindling, of which there is a nearly infinite supply. The Muslim-world popularizers poured metaphorical lighter fluid on the material they plucked from obscurity, and angry rioters caused the conflagration. By confusing spark with kindling, Hillary Clinton and other U.S. officials (plus many American intellectuals) are diverting some of the responsibility for violence away from the perpetrators and toward the creators of controversial speech.

You can see this throughout the Benghazi chapter in Clinton's latest memoir, Hard Choices. "This was not the first time that provocateurs had used offensive material to whip up popular outrage across the Muslim world, often with deadly results," she writes. Amazingly, she is not talking about the Islamists who dubbed Innocence of Muslims into Arabic and then broadcast it with fiery denunciation on Egyptian television, but rather the originator of the art, Nakoula Basseley Nakoula. Next sentence: "In 2010, a Florida pastor named Terry Jones announced plans to burn the Quran, Islam's holy text, on the ninth anniversary of 9/11." Once you begin to pin responsibility for faraway violence on acts of peaceful (if vulgar) free speech in America, the only thing standing between an artist and prison is an available crime.

On September 14, 2012, Hillary Clinton, Obama, and Vice President Joe Biden attended an Andrews Air Force Base ceremony for the surviving family members of the four U.S. personnel killed in Benghazi. If what some of those family members say about that meeting is true, the likely Democratic presidential nominee uttered one of the most chillingly anti-speech sentences from an American politician since Richard Nixon.

Charles Woods, the father of slain CIA operative Tyrone Woods, jotted down notes from that day in his diary. The passage about Clinton reads like this: "I gave Hillary a hug and shook her hand. And she said we are going to have the filmmaker arrested who was responsible for the death of my son." Two weeks later, Nakoula was arrested by federal authorities on charges of violating probation, for which he served one year in prison.

Woods, a retired lawyer and administrative law judge, has given consistent accounts of Clinton's remarks in several interviews over the past three years. "I remember those words: 'who was responsible for the death of your son,'" he told The Weekly Standard's Stephen Hayes in October 2015, while watching the former secretary of state's latest congressional testimony. "She was blaming him and blaming the movie."

Woods wasn't the only bereaved family member who heard a similar message that day. Patricia Smith, mother of the murdered Sean Smith, has testified in Congress (and reiterated in interviews) that Clinton told her "it was the fault of the video." A third witness, Kate Quigley, sister of Glen Doherty, told Boston Herald Radio in December that Clinton "knows that she knew what happened that day and she wasn't truthful. And you know that has come out in the last hearings, that she's told her family one thing and told the public another thing."

The October Benghazi hearing unearthed State Department notes from a Clinton phone call on September 12 in which she gave an altogether different version of events to Egyptian Prime Minister Hesham Kandil. "We know that the attack in Libya had nothing to do with the film," the note quotes Clinton. "It was a planned attack—not a protest." An email to her daughter Chelsea the night before (which is what Kate Quigley was referring to) stated that "two of our officers were killed in Benghazi by an al-Qaeda like group," which would also suggest a pre-planned attack more than the spontaneous mob outrage that Susan Rice was selling as late as September 16. At the hearings, Clinton chalked up these mixed messages to the fog of war: "There was a lot of conflicting information that we were trying to make sense of."

But that sense of nuance was absent from many Obama administration comments at the time. On the same day as the Andrews Air Force ceremony, White House spokesman Jay Carney stated categorically that the attack was "in response not to United States policy, not to obviously the administration, not to the American people. It is in response to a video, a film that we have judged to be reprehensible and disgusting."

And if the family members of two different fallen service members are correct, Clinton placed direct culpability for the attack on a California-based filmmaker and perhaps even vowed to have him arrested, something far outside the usual purview of a U.S. secretary of state.

On December 6, 2015, faced for the first time with questioning about what she said to Charles Woods and the others that day, Hillary Clinton told ABC's This Week that the survivors got their stories wrong.

"Some…family members of the Benghazi victims are saying you lied to them," George Stephanopoulos said. "The family members, as you know, say you told them it was by a filmmaker, you'd go after the filmmaker….Did you tell them it was about the film? And what's your response?"

Hillary's response? "No."

And the mainstream political media's response to this startling, potentially significant discrepancy? Almost total silence.

The 3 A.M. Phone Call

The First Amendment, and the American culture of free speech, come under the most pressure during times of acute national or international stress. The Sedition Act of 1798, criminalizing criticism of the federal government, was passed when the fragile young country was skirmishing with imperial France. Woodrow Wilson signed his own Sedition Act in the war-torn year of 1918. The post-9/11 world has seen unprecedented government crackdowns on leakers, journalists who protect their sources, and whistleblowers. (Regarding the latter, Hillary Clinton said during an October presidential debate that National Security Agency dissident Edward Snowden "broke the laws of the United States. He could have been a whistleblower. He could have gotten all of the protections of being a whistleblower. He could have raised all the issues that he has raised. And I think there would have been a positive response to that." The fact checkers at PolitiFact rated the claim "mostly false.")

In the immediate aftermath of the Danish cartoon controversy, of Benghazi, of Charlie Hebdo, and of the San Bernardino attacks, there have been renewed calls in the United States for scaling some of that free speech stuff back. "ISIS Influence on Web Prompts Second Thoughts on First Amendment," The New York Times headlined a piece on December 27.

So how will Hillary Clinton handle that next moment of stress? Well, look at how she's responded to San Bernardino: by breathing heavily down the neck of Silicon Valley to shut down jihadist communication on the Internet. "That would be constitutional if voluntary, legal experts say," the Times article notes dryly, "but not if the government exerted pressure on private firms to cooperate in censorship."

Attempting to patrol the space between communicators and their audiences is what Clinton does. "I've spent more than 30 years advocating for children and worrying about the impact of media," she said in a speech 10 years ago. Since then, she has focused increasingly on the threat of Islamic terrorists, and their ability to use the technology she has always distrusted. The Supreme Court may serve as a vigorous bulwark against legislation that encroaches on the First Amendment, but it is more deferential when the executive branch exercises its national security prerogatives. A second President Clinton will almost certainly test those limits. When it comes to the mythical "balance" between liberty and security, she knows damn well what side she's on.

"It doesn't do anybody any good if terrorists can move toward encrypted communication that no law enforcement agency can break into before or after," she said during the December Democratic debate. "I just think there's got to be a way, and I would hope that our tech companies would work with government to figure that out. Otherwise, law enforcement is blind—blind before, blind during, and, unfortunately, in many instances, blind after. So we always have to balance liberty and security, privacy and safety, but I know that law enforcement needs the tools to keep us safe."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Hail to the Censor!."

Show Comments (54)