Are You a Fan of Making a Murderer? Check Out These Exoneration Figures for 2015

Another record year for proving some people behind bars are innocent.

The Netflix series Making a Murderer has gotten huge media and public attention for its portrayal of the story of Steve Avery, who served 18 years in prison for sexual assault and attempted murder, only to be later exonerated and then arrested again and convicted in 2007 for murder.

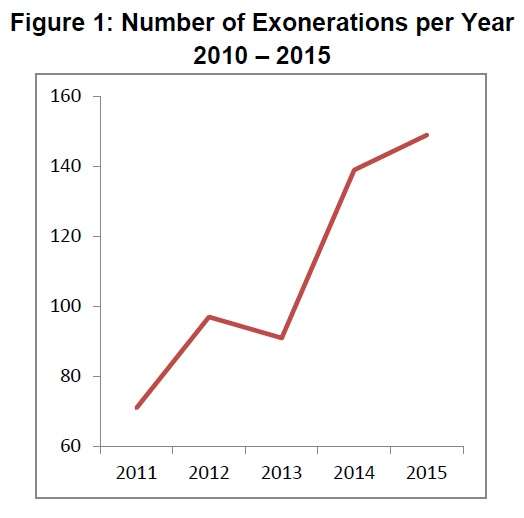

The National Registry of Exonerations at the University of Michigan is pivoting off the fame of the documentary series to highlight its annual figures showing how many other prisoners are found innocent, Their numbers for 2015 were released today and they show a new high in numbers. In 2015, 149 people (that the registry has documented) were exonerated of their crimes. This is an increase of 10 over 2014's numbers, which were themselves a record (note that when I blogged 2014's numbers, we registry had them initially at 125. These may increase as more information makes it to the registry. It's possible then that more than 149 people were exonerated last year.)

Here's some important statistics from the registry's report:

-

National Registry of Exonerations Those exonerated in 2015 had served an average among them of more than 14 years in prison.

- The flat numbers are small, but we've seen a doubling in the number of exonerations since 2011.

- 58 of those exonerated had been convicted of homicide. Five had been sentenced to death.

- 47 of those exonerated had been convicted of drug possession.

- 27 of the exonerations were from convictions connected to false confessions, primarily in homicide cases. Often the defendants were minors or had mental illnesses and/or intellectual disabilities.

- 44 of the homicide exonerations involved discoveries of misconduct by officials

- 44 percent of the exonerations were of people who actually pleaded guilty to their crimes, a record high.

- A record 75 exoneration cases were in situations where it turned out no crime actually even occurred. In the most egregious example, three men were convicted of setting a fire in Brooklyn that killed a mother and her five children. It turned out the witness who testified that she saw them leaving the building at the time of the blaze later admitted lying and the evidence did not prove that the fire was actually intentionally set.

As with last year's numbers, the registry gives a lot of credit for the exonerations to Conviction Integrity Units (CIU), which work with prosecutors' offices to fix false convictions. CIUs were involved in 58 of the exonerations. As with last year, special mention is made of CIUs in Harris County, Texas, (where a huge chunk of the drug-possession exonerations came from) and Brooklyn, where they saw they above-mentioned homicide exonerations. Texas and New York dominated the other states in the total number of exonerations last year. It's not necessarily because these two states have the most false convictions, the registry is quick to explain, but because those CIUs are so actively involved in fixing them.

Ultimately that means these releases, while increasing in number, may represent just the tip of the iceberg. The registry concludes in its 2015 report that there's still an epidemic that remains mostly hidden:

In 2014 and 2015 there were 16 exonerations of defendants who were convicted of murder in Brooklyn from 1988 through 1994; other such cases are pending. This concentration of bad murder convictions from the years of the crack epidemic cannot be unique to Brooklyn. We have no doubt that similar numbers of cases would be found in other cities around the country if the prosecutors in charge devoted as many resources to finding them as the Brooklyn District Attorney's Office.

In 2014 and 2015, 73 innocent defendants who pled guilty to low level drug crimes in Harris County, Texas, were exonerated by lab drug tests—and more to come. But how many innocent defendants have pled guilty in Harris County in cases for which no lab tests are available? And how many thousands more in the thousands of other counties across the country?

Read the full report, Exonerations in 2015, here.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

After watching Making a Murderer, I am convinced that the police and prosecutors framed a guilty man.

Me too. They obviously planted some evidence, but there also was evidence that they really couldn't have faked that Netflix declined to examine.

I've read comments similar to this several times, but I have yet to see any remotely convincing evidence that wasn't in the documentary. Brendan Dassey obviously had nothing to do with it. It's possible that Steven Avery committed the murder, but the available evidence doesn't support the prosecutions theory of the case. There are several contradictions (e.g. did he kill her in the house or the garage and where is all the blood). I think someone else on the Avery complex committed the crime and framed Steven. Everything would make sense. The planted evidence, the missing evidence, access to do the framing all makes sense if it was somebody else in the complex.

How do you shoot someone with his gun that hangs above his bed, get DNA from the bullet, and place the gun back above his head if you're framing him?

That combined with the Avery DNA under the hood of the car, him buying shackles the week before, human remains found in the burn pit, the *67 calls to Halbach.

Sometimes the simplest answer is the real answer---he killed Theresa Halbach.

The saddest part is that all those years in prison as an innocent man likely cemented him as the kind of guy who would be capable of such a crime.

FYI, Avery was already a known low life BEFORE being put in prison the first time - he was railroaded because he was already on the radar and something he didn't do got pinned on him. I don't think he was a choir boy wrongly convicted who then turned to a life of hard crime on the inside.

The cops?.the detectives?.the prosecutors?.the judges?..if you're involved in these cases, you should be hounded, shunned, mocked and flipped-off for the rest of your lives. And when possible, jailed.

The various stages of immunity for these positions should be modified/eliminated.

Immunity was just made up out of whole cloth by judges, anyway. It doesn't exist in the constitution or by legislation.

"44 of the homicide exonerations involved discoveries of misconduct by officials"

And how many of those officials were prosecuted for their crimes? Zero would be my guess.

Every year is the hottest year in the history of history.

And every year, more exonerations occur.

Coincidence? I think not.

max CO2 = max justice

The police and prosecutors do not work for justice, they work for convictions. Once they have what they think is a good suspect, that's it, case closed. "It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer",

...as expressed by the English jurist William Blackstone in his seminal work, Commentaries on the Laws of England, published in the 1760s.