You Don't Have to Oppose Abortion to Worry About Planned Parenthood Video Indictments

Turning journalistic deception into legal matter can have a chilling effect.

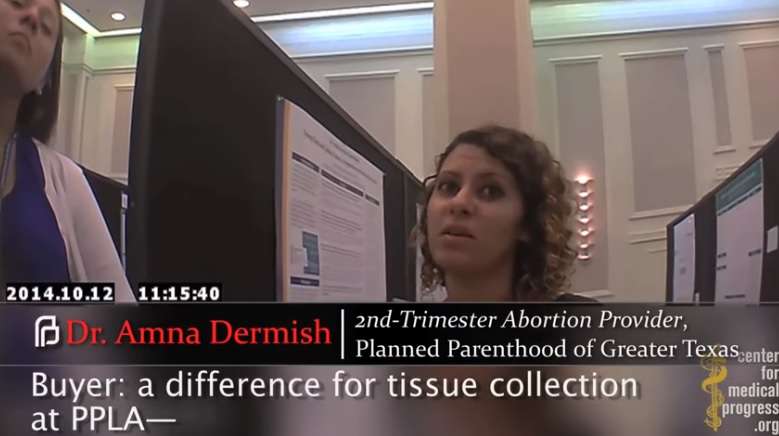

A grand jury in Texas responded to an undercover investigation of Planned Parenthood's fetal tissue practices by indicting not employees of the abortion and women's healthcare provider but rather the investigators. They are charged with using fake California identifications for the investigation (a felony) and attempting to buy fetal remains (a misdemeanor).

Law professors Sherry Colb and Michael Dorf, who have written a book about the relationship between arguments used for abortion rights and those used for animal rights, took to CNN to express concern about these indictments. They are pro-choice and support Planned Parenthood. Nevertheless, they are concerned about how indictments like this could affect citizen investigations not just of Planned Parenthood but elsewhere:

The felony charge of tampering with government records relates to their alleged use of false IDs, and the misdemeanor charge of attempting to buy fetal remains seemingly overlooks the fact that Daleiden and Merritt were only posing as buyers to expose what they believed was illegal conduct by others.

Whatever the precise facts of this case prove to be, the prosecution has broader implications, and not just for abortion and anti-abortion speech. Undercover exposés play a vital role in informing the American public of important facts that would otherwise remain hidden.

For example, Upton Sinclair's muckraking 1906 novel "The Jungle" was based on his incognito work in the Chicago meatpacking industry. Timothy Pachirat's more recent "Every Twelve Seconds" shows the impact of a modern slaughterhouse on the workers and animals unlucky enough to find themselves in its confines. Unfortunately, the courts have not consistently protected undercover reporting.

Animal rights activists who gain access to farms, slaughterhouses and laboratories by disguising their true intent may face criminal charges. In a carefully reasoned opinion last August, a federal district judge invalidated Idaho's "ag-gag" law on First Amendment grounds, but the state has appealed, and the ultimate outcome remains uncertain.

Read more here, and more about striking down "ag-gag" laws here.

I do want to take issue with some of Colb and Dorf's argument though. They do not seem to want to moderate the rights of citizen or undercover journalists with any sort of understanding that there's such a thing as private property. They complain about censorship that can be brought about through the application of general laws that aren't about speech at all, just as with this case. But they also seem to think that the antidote for this is essentially the government giving a pass to all sorts of possible crimes, including trespassing, in the pursuit of a story:

To be sure, legislators and judges have good reason to tread carefully in recognizing a journalist's right of access to private property. In the age of Facebook and YouTube, anyone with a mobile phone can plausibly claim to be a citizen journalist.

Accordingly, any right of undercover access would need to be limited to matters of genuine public concern, lest snoops posing as door-to-door salespeople and housekeepers violate legitimate interests in privacy. Even journalists or activists investigating a story in which the public has a real interest should not be given carte blanche to expose truly private facts, such as the identity or medical history of Planned Parenthood patients.

Problem one: Anyone with a mobile phone is a citizen journalist. Journalism is a thing that people do, not a thing that people are. Problem two: Who would be the person who would be deciding what are "matters of genuine public concern" in the first place? It would undoubtedly be a government authority of some sort. Would people have to seek permission in advance from this nebulous authority figure for permission to engage in undercover journalism? Or would they have to hope after the fact that these same government authorities will objectively make a decision? Why on earth would anybody trust such a system?

Like every other right, journalistic practices are limited to the extent that they interfere with the rights of others. Maybe the appropriate way to evaluate investigative journalists' behavior is to ask "Whose rights were violated here?" when trying to determine whether the law should apply. Whose rights did the Center for Medical Progress violate by having fake identifications and pretending they wanted to buy fetal tissue (when they obviously had no intention of doing so)? That's a little bit different from the government giving clearance to activities like trespassing and vandalism to try to get access to where somebody thinks something bad may be happening.

Show Comments (39)