Terrorism In Europe is Less Common and Less Deadly Than in the Recent Past -- And Doesn't Justify Expanded Repressive Surveillance

International security researcher: "Western Europe is safer now than it has been for decades and is far safer than most other parts of the world."

The Paris terror attack that killed 129 and wounded over 300 in November was brought up three times during last night's Republican candidate debate, and obviously will continue to be used as a touchstone about an ongoing and unprecedented terror threat demanding firm actions.

The attack was certainly horrific and monstrous, as was the attack on Charlie Hebdo, the satirical magazine, that happened a year ago last week. And, as Reason editor-in-chief Matt Welch detailed last month, those attacks have indeed triggered immense civil liberties restrictions that the French political class seeks to make permanent.

But those atrocities were not, even within living memory, an unprecedented example of such chaotic evil in continental Europe that seem to demand an unprecedented response. Western Europe has faced, and survived, even more heinous and continuous patterns of multiple-casualty criminal terror attacks, most particularly in the 1970s.

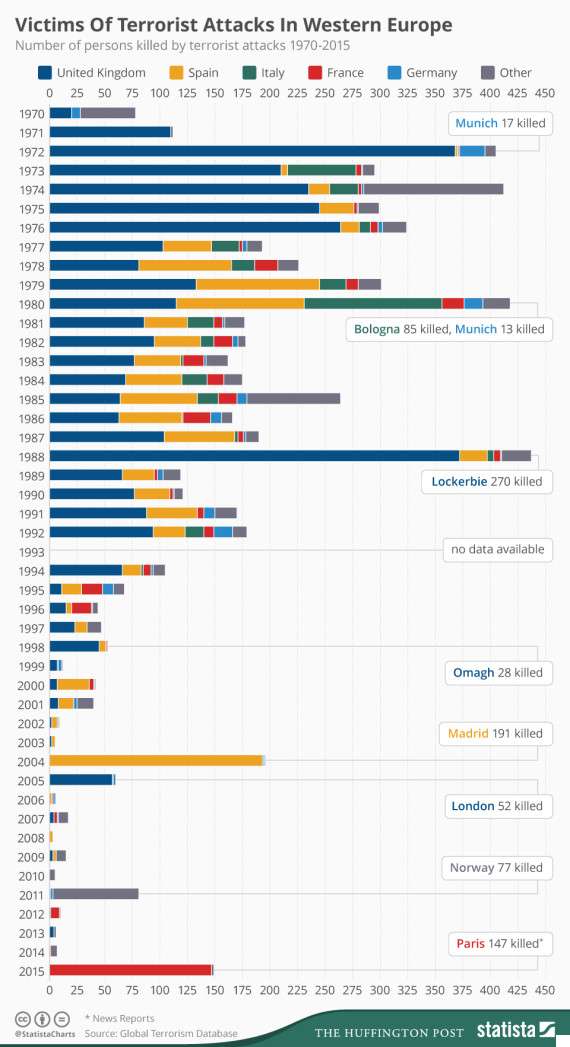

This graph below, produced by Huffington Post UK shows an overall pattern in the 1970s of yearly terror deaths in Europe exceeding 2015's count, over 200 nearly every year. (The U.K., dealing with the now-defunct Irish Republican Army, always had the worst of it.)

The numbers revealed in that graph led Dr. Adrian Gallagher, associate professor in international security at Leeds University, to say that: "Western Europe is safer now than it has been for decades and is far safer than most other parts of the world."

Banks, train stations, public plazas, and airports and airplanes, were targeted in Italy in multiple-casualty attacks from the late '60s to early '80s, with the responsible parties including Palestinian and far-right groups.

While most individual terror incidents were not multiple casualty attacks in the Paris mode, Italy from 1968-82 suffered over 4,000 attacks on people and over 6,000 attacks on property by terrorist gangs.

France itself faced frequent terror attacks throughout the 1970s and 1980s as well. The overall casualty rate from such attacks was not staggeringly large in toto, though they included a 1982 grenade-and-gun attack on a restaurant that killed six and injured 22, and an attack on a popular retail store in 1986 that killed five and injured over 100. (The Paris attack in November was indeed the most murderous singular terror blow in modern French history.)

West Point's Combating Terrorist Center has a decent overview of the '80s terror threat in France, which came largely from Palestinian or Algerian related groups, and an assessment of that nation's counterterror tactics prior to this current wave of terror attacks.

Those French tactics include treating terrorists as criminals rather than enemy combatants, arresting or detaining on mere suspicion of association with groups thought to be planning terror attacks, agent provocateur infiltration and incitement to minor crime to speed up arrests of suspected troublemakers, and direct traditional "spying"—observing and recruiting/turning suspect individuals or groups. French intelligence agencies have almost zero public oversight or review on their actions.

Following is a quick reminder of some (this list is suggestive, not comprehensive) specific organized pre-ISIS terror threats Europe faced in that era, and a broadbrush look at how they were quelled. (For a more granular and wide-range look, Wikipedia has decent pages dedicated to French and German terror, to start.):

• Red Brigades (Italy) A communist guerrilla army active from 1970-82, aiming their terror at symbols of industry and conventional politics.

According to the 2007 book by Robert J. Art and Louise Richardson, Democracy and Counterterrorism: Lessons from the Past, their active membership did not exceed 800, and 150 deaths can be directly attributed to their actions, with another 200 attributable to other communist and fascist revolutionary bands active in Italy in roughly the same period. Red Brigades tended toward more directly targeted attacks on individuals in industry and politics and more sheerly criminal acts, rather than mass-murder public bombings.

Allesandro Orsini in his 2011 book Anatomy of the Red Brigades: The Religious Mind-set of Modern Terrorists (Cornell University Press), characterized them (in language that echoes how ISIS is often framed today, minus the Islamic angle) as:

"essentially eschatological, focused on purifying a corrupt world through violence. Only through revolutionary terror, Brigadists believed, could humanity be saved from the putrefying effects of capitalism and imperialism…this political-religious concept of historical development is central to understanding all such self-styled "purifiers of the world." From Thomas Müntzer's theocratic dream to Pol Pot's Cambodian revolution, all the violent "purifiers" of the world have a clear goal: to build a perfect society in which there will no longer be any sin and unhappiness and in which no opposition can be allowed to upset the universal harmony."

Art and Richardson credit the Brigades fade out in some part to Italy's Communist Party, striving to be taken more seriously as a participant in liberal democracy and to avoid open connections to armed violence. Toward that goal, the Party backed away from even implicit support for that violent version of communist revolution. Given that current Muslim terror is not connected with any forces or organizations actively seeking domestic respectability, that analogy may not be particularly useful for current radical Muslim terror threats.

The authors also discuss some toughening of police tactics and lessening of suspects' right in Italy in the late 70s and early '80s. These policies included making mere associating with what the state defined as terror groups a crime, doubling times people could be held in preventive detention, demanding reports to the government on every rental property transaction or sale, and increased wiretap powers.

But the most effective policy, they maintain, was a basic offer of some leniency to terror group members who essentially came in from the cold, gave up info on comrades, and abjured their terror associations, in exchange for reduced sentences for crimes they admitted to.

The researchers report 389 Brigadiers were turned this way, very significant in a group of such small size. There are no public signs that such tactics are being contemplated with modern Muslim terror. Unrepetent Brigadiers tend to attribute their fading away not to any successful suppression attempts, but rather to changing social conditions that made Italians less likely to support revolutionary violence. (Not that that many did to begin with; attributing changes in groups that amounted to fewer than 1,000 people to overarching social or economic forces is always an iffy proposition.)

• Baader-Meinhof Gang (aka Red Army Faction [RAF]) Communist guerrillas active in Germany from 1970-early '90s, with complicated associations with various other revolutionary Marxist movements also active at the time. They received some of their training in Jordan and were allied with the PLO (and also received support from the communist government of East Germany). Their activities have been blamed for around 34 deaths and many more wounded.

Despite their string of bank robberies, car thefts, department store arsons, and killings, at one point before their leaders were arrested 25 percent of under-30s Germans had some sympathies with the radical-chic leftist killers who played on American military presence during the Vietnam war (after Vietnam ended, NATO and general foreign military presence was a frequent target), supposedly evil corporate dominance of the Third World, and supposedly unreconstructed Nazi presence and influence on the postwar German government.

Part of the German reaction to the RAF involved increasing federalization of law enforcement and blocking people of believed radical tendencies from certain government jobs. A small cadre of their leaders were all arrested in 1972, though murderous attacks, including on the West German embassy in Sweden and the murder of a Federal Prosecutor involved in the case (along with his driver and bodyguard) from RAF continued, and the elimination of their first generation leaders did not destroy the group. Time, changing social and economic conditions, and the collapse of the communist bloc were some of the things that helped. (And again, the number of people involved actively in the mayhem was so small that sometimes overarching social cause explanations might be beside the point.)

• ETA (abbreviation of Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna ("Basque Homeland and Liberty"). Basque separatist terror gang operating in Spain, seeking a separate state for the Basque. They also had a significant Marxist-Leninist influence. They kidnapped, robbed, and extorted for funding and terror, and remained an active menace from 1968 through the first decade of the 21st century. They killed 829 people over the years, including 343 civilians.

In the early years of the ETA Francisco Franco's regime's repressive measures often worked to increase sympathy and recruitment for its cause, and its most murderous years were post-Franco. (The ETA succeeded in assassinating Franco's likely successor, Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco.) Although Spain in later years responded with what some saw as appeasement, including some autonomy for Basque provinces (including an Autonomous Basque Government in some provinces where the Basque language was official) and some pardons for ETA members (after renouncing terrorism), Spanish police were very tough on suspected ETA collaborators when they nabbed them, and were even willing (eventually) to cross into France to attack and kill ETA members.

After 9/11 Spain got the rest of Europe to declare and treat ETA as mere terrorists and not a legitimate representative of national aspirations, and banned the Batsuna political party for its ties to ETA. In the end, according to Teresa Whitfield's book Endgame for ETA: Elusive Peace in the Basque Country, despite how depleted they were in numbers and despite Spain's public insistence on unconditional dissolution, the final end was the result of secretive negotiations "between the nationalist Left, ETA, and the government through trusted international facilitators." How relevant those circumstances of a fight against internal nationalism can or will be to a fight against often foreign-based Muslim terror is uncertain.

Some other relatively high-casualty revolutionary groups among the many active in Western Europe in the late '60s through 70s include Italy's Ordine Nuevo (linked to 38 deaths), the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (linked to 50 deaths) and Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (likely responsible for over 85 deaths).

Barbie Latza Nadeau writing last January in the Daily Beast surveyed some experts on '70s European terror, seeking lessons that might apply to now. (This was post-Charlie Hebdo, but before November's more violent and coordinated Paris attacks.)

Jacco Pekelder, a professor of Political Violence and Terrorism at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, noted some techniques used to quash the Red Brigades that current anti-terror efforts might work against:

The Red Brigades ultimately were defeated through a concerted program that focused on the "neutralization" of terrorists who were exposed—often by the pentiti [former terrorists who had turned their back on the cause]—hunted down, jailed or killed. That, Pekelder says, is not happening yet in the current wave of terrorism. Instead he says the mass sweeps of potential jihadist fighters tend to punish a whole group of people who happen to be the same ethnic race or religion. Instead, he says, more emphasis has to be placed on understanding how vulnerable people think and operate on the margins of society.

"In 70s it used to be pamphlets, now it is the Internet," that must be utilized to reach the next so-called homegrown terrorists before they self-ignite. "This is the battle ground we have to work in, but you have to be completely steadfast in terms of not making the battle about freedom of ideas and freedom of religion." …..

Rounding up the usual suspects rather than trying to understand who they are can be very counterproductive. "It is a compromise to round them up," he says. There's often a strong element of racial and religious profiling, The danger is that law enforcement will fulfill the terrorists' prophecies of repression and thus help them recruit new cannon fodder. Whereas if you can win over those people who are leaning toward terrorism, and pull them away from it, as Pekelder puts it, "you win the war."

The reasons those '70s and '80s threats largely disappeared are complicated and in many cases bound to particular personalities and time-specific local or national facts. They can't be applied in some straight analogy to today.

But those who see the current European terror threat as so unprecedented that any means to quell it are valid should remember those '70s and '80s terror threats did fade without widespread civil liberties violations or an all-round electronic surveillance state.

But modern Paris, as noted above, has adopted some severe efforts to fight the current terror threat, as has been amply documented here at Reason by Anthony Fisher.

These include police advocacy for killing public wi-fi and becoming the first European nation to ban use of the Tor anonymizer service, actual arbitrary house arrests of people expected to cause public trouble (even of less than the "murderous spree" type), and a general three-month state of emergency including:

- Expanded powers to immediately place under house arrest any person if there are "serious reasons to think their behaviour is a threat to security or public order".

- More scope to dissolve groups or associations that participate in, facilitate or incite acts that are a threat to public order. Members of these groups can be placed under house arrest.

- Extended ability to carry out searches without warrants and to copy data from any system found. MPs, lawyers, magistrates and journalists will be exempt.

- Increased capacity to block websites that "encourage" terrorism.

Even prior to the Paris attacks, as Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) pointed out, France had a mass surveillance system even more thorough and with fewer civil liberties protections than the U.S.'s—and it failed to prevent or even detect the Paris slaughter.

I also wrote in 2011 of an even older, and even more potent, terror threat in the heart of the powers of Europe. That was the now-extinguished threat of revolutionary anarchism, which, as I wrote, "roughly from 1880 to 1910…claimed the lives of only about 150 private citizens but also killed a president, a police chief, a prime minister, a czar, a king, and an empress" but morphed from imagined existential threat to historical curiosity. That is a trend that seems to repeat with terror threats against the West.

Show Comments (47)