Fentanyl-Laced Heroin and Other Deadly Consequences of Prohibition

How the government makes drugs more dangerous

Heroin spiked with fentanyl, a highly potent narcotic, was in the news this week because of recent overdose deaths in New York and Connecticut. In my latest Forbes column, I explain how prohibition makes heroin and other drugs more dangerous:

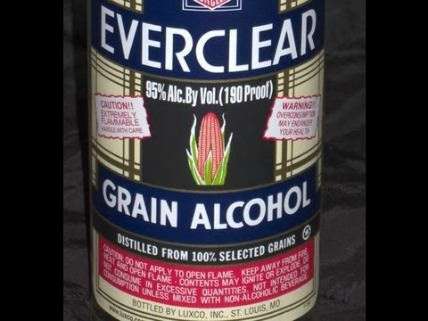

Remember the guy who bought 80-proof vodka that turned out to be 190-proof Everclear and died from alcohol poisoning? Probably not, because that sort of thing almost never happens in a legal drug market, where merchants or manufacturers who made such a substitution, whether deliberately or accidentally, would face potentially ruinous economic and legal consequences. In a black market, by contrast, customers frequently get something different from what they thought they were buying: something weaker, something stronger, or some other substance entirely. As The Washington Post notes in a recent story about fentanyl-laced heroin, the results can be fatal.

This phenomenon is so familiar by now that calling it an unanticipated consequence of prohibition suggests that people writing drug policy know nothing of its history. It may not even be accurate to call uncertainty about the contents of black-market drugs an unintended consequence of prohibition, since it serves prohibitionists' avowed goal of discouraging drug consumption. After all, the more dangerously unpredictable drugs are, the less likely people are to use them. That calculation, of course, sacrifices the interests, and sometimes the lives, of undeterred drug users for the sake of protecting more risk-averse people from their own bad decisions. But that is what prohibition is all about.

For anyone who doubts that making drugs more dangerous is an entirely predictable, if not intentional, result of prohibition, here are a few recent examples to consider, starting with the one highlighted by the Post.

Show Comments (8)