Why It's Hard to Trust the Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund

When the economy is struggling, more people falsely apply for disability benefits.

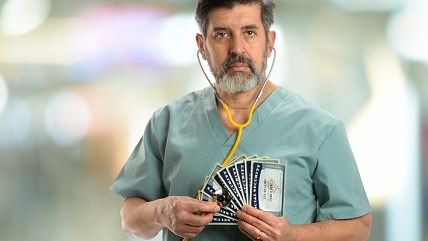

Have you ever wondered why your television screen is often filled with advertisements from law firms touting their ability to land money for the disabled? It's because helping people obtain federal Social Security disability benefits has become a lucrative industry in the past decade. But it would be a mistake to only blame the legal profession. After all, lawyers are merely taking advantage of a program that frequently encourages people with dubious disability claims to seek benefits, especially when the economy is down.

According to the Social Security trustees report released at the end of July, the disability insurance trust fund will run out of money by the end of 2016. Without reforms, millions of Americans will receive an automatic 19 percent reduction in their Social Security Disability Insurance benefits.

That the program is short on cash is not surprising, considering the tremendous increase in benefits and recipients. According to the Social Security Administration, 2.6 million Americans were collecting SSDI in 1970. In 2014, that number reached 10.9 million. Today the program pays about $142 billion. Adjusted for inflation, that's double what the program cost in 1998.

The statistics show large increases in applications for disability benefits when the economy is struggling and unemployment is rising but fewer applications when the situation is reversed. Given that people obviously don't become more or less disabled depending on how the economy is performing, it means that people are using the program as a form of unemployment insurance.

How did we get here? When SSDI was implemented in the late 1950s, it was intended to provide benefits to those who were too disabled to work but weren't yet eligible for Social Security benefits. However, eligibility standard changes implemented in 1984 shifted screening rules from a list of specific impairments to a process that put more weight on an applicant's reported pain or discomfort, even in the absence of a clear medical diagnosis. This results in more workers being awarded benefits based on ailments that aren't easily diagnosed and depend on patient self-reporting, such as back pain.

Adding to the problem is that if people are initially denied benefits, they can appeal to an administrative law judge, or ALJ. In theory, these judges impartially balance the claims of applicants against the interests of us taxpayers. Unfortunately, many judges don't. In May, my colleague Mark Warshawsky and George Mason University economics student Ross Marchand noted, "In 2008 judges on average approved about 70 percent of claims before them, according to the Social Security Administration."

They added, "Nine percent of judges approved more than 90 percent of benefit requests that landed on their desks." As their data show, those judges who are generous with benefits are also consistently generous over time. This shouldn't be the case, of course, because judges are randomly assigned cases. This is problematic for taxpayers. In their upcoming Mercatus Center study, Warshawsky and Marchand estimate that over the past decade, decisions from these overly generous judges will cost taxpayers $72 billion.

As the authors note, ALJs have greater incentives to award benefits than to deny them, because approving people involves less paperwork than denying them. Considering the payoffs for applicants (the average SSDI benefit amount is $1,165 per month but can reach $2,663), as well as the lack of incentives to stop appealing when denied and the incentives for lawyers to push their clients through the appeal process, judges—especially the generous ones—are faced with huge caseloads.

The system is in dire need of reform. On the ALJ front, Warshawsky and Marchand recommend reducing the judges' workload to 500 cases per year and ending lifetime tenure by reducing it to 15 years because the generous judges are the long-serving ones.

But lawmakers could also scale back eligibility rules so that benefits only go to those who can prove their inability to work. That might just make the TV ads stop and make the SSDI program solvent again.

COPYRIGHT 2015 CREATORS.COM

Show Comments (24)