In Wake of Fatal Shooting, Louisville Cops Shut Down Station Rather Than Meet With Local Police-Reform Advocates

Recent incidents in Louisville reflect a wave of "officer-involved shootings" and community-cop issues in Kentucky and Southern Ohio cities.

Activists are asking the city of Louisville, Kentucky, for reform in its "interactions with its citizens of color." Last week's fatal shooting of Deng Manyoun by a Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) officer, followed by a local police union president calling protesters "race-baiters" whom the community should "rise up" against, are the latest incidents in what some locals describe as "comply or die" behavior from Louisville cops.

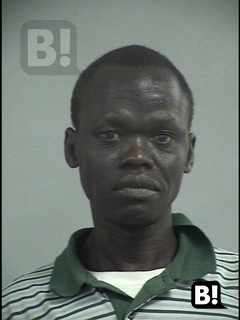

On the afternoon of Saturday, June 13, Officer Nathan Blanford encountered Manyoun, a 35-year-old Sudanese immigrant who didn't speak English, while investigating a call about an assault in historic Old Louisville. A resident of the neighborhood, Manyoun was stumbling in the street as if he were drunk. It's unclear whether Manyoun was stopped by Blanford because he was thought to be a suspect in the assault or because he appeared intoxicated. Video of the incident from a store surveillance camera shows the two men arguing, then Manyoun walking away. He returns into the frame wielding a flagpole (complete with red-and-blue striped "Open" sign) grabbed from the front of a nearby smoke shop. Manyoun can be seen running at the officer while swinging the pole. It breaks in half as the officer backs away and fires his gun twice at Manyoun, who later died in the hospital.

At a meeting the next day, members of activist group Stand Up Sundays questioned why Blanford didn't try to stop Manyoun with a Taser, mace, or a baton first. "De-escalation tactics are not used when it comes to people of color," said Tara Pruitt at the meeting, covered by The Post-Courier. "The officer went first to kill a man with his gun," said organizer Chanelle Helm. "He did not subdue him."

At a press conference, Louisville Police Chief Steve Conrad defended his officers' actions. "Quite frankly, when you've got somebody coming at you with a dangerous instrument of that type… I don't know… that the officer had the opportunity to transition to a less lethal option," he said.

Soon thereafter, a letter released by a local Fraternal Order of Police chapter called the activists "sensationalists, liars and race-baiters" and suggested that people might have to "rise up" against them. "Your ridiculous demands and anti-law enforcement attitude has reached a level that is unacceptable," wrote David Mutchler, a police sergeant and FOP chapter president. "You want our attention? Well you have it. Consider yourselves on notice."

In response, protesters headed to the LMPD Monday, June 22, to deliver a list of "demands seeking greater transparency in policing activities and higher standards of accountability." These included things like requiring any officers involved in fatal shootings to give a recorded statement within 48 hours, speeding up the implementation of police body cameras, and firing Mutchler. But when activists arrived at police headquarters, they found the doors locked.

"We had received information that the protesters planned to come into the headquarters building and occupy the building," Conrad told local news station WAVE 3. "We had additional intelligence that indicated that there was at least the potential for violence."

"It is unconscionable for the Metro Police Department to opt to close down operations at their headquarters, rather than engage with community members who have peacefully united to demonstrate their First Amendment rights," said former city councilwoman Attica Scott in a statement. "This cowardice does not lead to positive change for the betterment of our entire community–it only hinders our capability to make progress on issues of policing and racial justice."

Last December, The New York Times reported on the evolution of community-cop relations in Louisville: "Louisville, 270 miles east of Ferguson, had its fraught Michael Brown moment, or moments, when several young black men died in police shootings from 1999 to 2004. Interactions between the police and black residents have improved since then, people here say, but remain a work in progress."

In nearby Cincinnati, Ohio—a place with close cultural and economic ties to Louisville—the picture is similarly filled with starts and stops. After a U.S. Justice Department investigation and consent decree in the early 2000s, the city has embarked on a series of significant reforms that have transformed community-cop relations from totally poisoned to merely tense. A May 2015 profile in The Atlantic explores this transformation, noting that "the city that once served as a prime example of broken policing now stands as a model of effective reform," but "the lessons of Cincinnati are complicated. Success required not just the adoption of a new method of policing, but also sustained pressure from federal officials, active support by the mayor, and the participation of local communities. If Cincinnati is a model of reform, then it is equally a sobering reminder of how difficult it can be to change entrenched systems."

I was in Cincinnati, my hometown, last week. When I arrived, the radio in my dad's truck was tuned to talk radio, where some conservative host was blasting the "communists, anarchists," and other no-goodniks who were feared to be descending from nearby big cities to agitate. The (unfounded) fear turned out to be in response to the fatal June 10th shooting of 22-year-old Quandavier Hicks by a Cincinnati cop, who had showed up at Hicks' Northside house after a woman accused him of harassment. Officers say Hicks reached for a rifle before they shot him.

A few days before I left town, Cincinnati was once again in an uproar over a shootout that left one officer and one civilian dead in the inner-ring suburb of Madisonville. The civilian, 21-year-old Trepierre Hummons, called 911 to report a person with a gun acting erratically; he failed to mention that person was himself. When cops showed up, Hummons opened fire, hitting 48-year-old Officer Sonny Kim. Both Kim and Hummons died later at the hospital. Hummons had been texting friends about plans to commit suicide by cop but none of them notified police, lamented Cincinnati Police Chief Jeffrey Blackwell.

Lexington, Kentucky—about 90 minutes from both Cincinnati and Louisville—has also had several fatal shootings by city police in the past year. And all three cities have seen a recent spate of homicides and shootings in general. Just last night, an anti-violence march in downtown Cincinnati was halted by three men shooting at one another at a playground, resulting in the death of an 18-year-old.

Some have worried than an alleged "epidemic" of heroin and prescription opiate use in these areas has led to increased violence; whether or not that's true, the issue has definitely led to more police patrols and investigations, as well as cries to increase penalties for heroin possession and sale. Anti-heroin activists have complained that proposals focus too much on finding and punishing users rather than addressing underlying addiction via community services.