Celebratory Protests in Baltimore

Charm City activists react to the Freddie Gray indictments.

The plan had been to demand an indictment of the six officers who had captured and transported Freddie Gray, the young man who died in police custody here in Baltimore last month. But by the time the supporters of Baltimore United for Change had assembled downtown yesterday afternoon for their march, State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby had announced that the cops were all being charged.

That gave the gathering a celebratory air. It also made the demands more open-ended. Molly Amster, the Baltimore director of Jews United for Justice, announced before the parade began that "we're not done just because we got an indictment….People need equality of opportunity, equality of education, equality of housing." By the time we'd marched to City Hall and various speakers started addressing the crowd, a more specific cause was getting mentioned with particular frequency: to reform the state's Law Enforcement Officers' Bill of Rights, which among other provisions gives cops accused of misconduct a 10-day cooling-off period before they have to tell investigators anything.

When the Baltimore United demonstrators arrived at City Hall, they filled about half the square in front of the building. The throng grew larger as the afternoon progressed. At one point another march, coming from who-knows-where, materialized on the north end of the plaza, and suddenly the place felt packed. Besides the protesters and reporters, there were human rights observers from Amnesty International and legal observers from the National Lawyers Guild. (The city had issued "peacekeeper passes" to some of the Amnesty people, allowing them to stay out after the 10 p.m. curfew. But that night the passes would be revoked, with the city claiming that counterfeits were floating around.) There was also a fellow with a sign that said "Free Cake." This turned out to be not a demand but an advertisement: He and some friends were giving out cake.

And then there were the well-armed National Guardsmen lined up between the demonstrators and City Hall. Across the road, up on a roof, yet more troops were in position, ready to shoot.

The only public official to receive any praise from protesters, at least when I was in earshot, was Mosby. Gov. Larry Hogan was damned for blocking reforms of the LEO Bill of Rights. Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake was derided for imposing a 10:00 curfew, and for generally seeming to be in over her head. I baited one activist, an old friend of mine who would prefer I not quote her by name on this subject, by bringing up Martin O'Malley, the former Baltimore mayor, former Maryland governor, and likely presidential candidate who had made a big point after the riot earlier this week of cutting short a European tour to return to the city. "I like candidate O'Malley," my friend told me, alluding to his decision to run to Hillary Clinton's left. "But Mayor O'Malley…" She rolled her eyes, then brought up the hecklers who've been giving the man a hard time when he pops up in different places around town. O'Malley played a big role in amping up the aggressiveness of the Baltimore police, and the unrest here hasn't done his campaign any favors.

When the Baltimore United rally formally ended, some protesters stayed in the square while another group paraded away. I thought about following the march, but I stuck around a while to watch some people cause trouble for Geraldo Rivera, banging a homemade drum and otherwise creating the sort of racket that makes it difficult to do a TV report:

This was actually a little friendlier than the reception he had gotten when he first showed his face. At one point, well over half the crowd had been chanting "Go home!" at him.

By the time I was ready to leave, I wasn't sure where the marchers had gone. I decided the best way to find them was to follow the flock of police helicopters, who at that point were hovering several blocks away. I fell in with a group of women in headscarves, one of them carrying an NAACP sign. They had gotten the same idea. Gradually more people joined us as the choppers moved further north. We checked our phones, looking for updates on the protest's location. We heard the marchers were passing the prison. By the time we got there, with one guy shouting his support out a window (or shouting something, anyway), we heard they were at the train station. By the time we got there, we heard the march had entered West Baltimore.

But which march? By this time, we were a pretty long line of people ourselves. Drivers were honking and yelling encouragement as they passed us, some of them raising their fists in power-to-the-people salutes. One of the headscarved women looked over her shoulder and gave a surprised start. "Are all those people following us?" she asked.

"We're following each other," a protester replied. Typed out like that, it looks like some sort of metaphor. But he meant it literally, and he was right.

Finally, on North Avenue, we caught up with the tail end of the march—or, perhaps, the tail end of another group of people looking for the march. At this point, I didn't think there was a difference. We ended up at Penn North, a West Baltimore neighborhood had been hit hard by the rioting a few nights earlier but now was in block-party mode. A caravan of cars drove through the street. Some had people standing on top of them. Little kids stuck their heads out the car windows, holding Justice for Freddie Grey signs. A jazz band jammed on the corner. Some friendly folks were handing out pie. Two strangers realized that they were both comic-book fans. "Nerds unite!" one yelled. "It's Avengers day too!" the other shouted back happily.

Even the National Guard was in a good mood, returning waves from the children in the cars. When a passing van cranked up "Fuck the Police," it cracked some of the Guardsmen up.

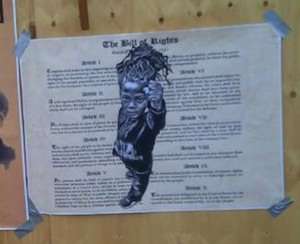

This demonstration had a demand too. "Convict all six!" a man shouted. "That's the new stuff!" Behind him a guy wore a CONVICT ALL SIX t-shirt. (That was fast.) Posters around the neighborhood featured the full text of the Bill of Rights with a dreadlocked figure raising a fist. I passed a rowhouse with one handlettered sign on the door and another between the windows. The first said, "FREDDIE'S FINAL 30 MIN.: SHACKLED IN PAIN. END POLICE TERROR!" The second said, "MURDERERS SHOULDN'T GET PAID VACATIONS. DISARM THE POLICE."

On the subway back downtown, an old guy named Benny plopped down in the seat behind me. "I've had about enough protest for life," he said. His feet were tired. Mine too.

"I support what they're doing," he told me. "Well, not the people who were looting." He paused. "They were destroying their own neighborhood. They could have gone to where the rich people live, but they're too scared." Another pause, while he realized how that last remark might be construed. "Not that I'm saying they should do that," he added. "It's just, why destroy your own shit?"

Off the train, I made my way back to City Hall, where the plaza was still filled with protesters. As a row of grim-looking cops filed past me, a bunch of civilians started humming the Darth Vader theme. Someone was speaking to the crowd, and he had a big Workers World Party banner behind him. I ran into my anarchocommie friend Flint Arthur sitting off to the side. "This is the hardcore socialist and anarchist left," he said, gesturing to the demonstrators. He informed me that the crowd had voted to defy the curfew, but that they hoped the mayor would revoke the rule before 10.

"Are you here to take a stand for freedom of movement after dark?" he asked, his voice adopting a mildly ironic tone.

I patted a piece of paper in my pocket. "In theory," I told him, "I can stay out after 10, because I'm credentialed press."

"Oh, you're gonna pull that," he chuckled.

"But I'm not sure I can get away with it," I continued. "I called up the police to ask what sort of credentials I needed, and they said whatever my publication provided should suffice. My boss told me to make my own, so I printed up this press pass, and I was gonna buy a lanyard and a badge holder at Staples on the way into town. But they'd been looted." Without the lanyard, my credentials' homemade quality was perhaps a bit too obvious, and I didn't know how forgiving the cops were going to be. Flint found this funny. So did I, actually.

By 10 the protesters had mostly dispersed, despite the earlier vote to stay. (There's a voice/exit lesson in there somewhere.) The cops made a few arrests, or so I hear; me and my DIY press badge departed about 15 minutes before the crackdown hour. If I want to report from inside a jail cell, I'm sure I'll have plenty more opportunities between now and the six cops' trial.

Show Comments (81)