'A Solution That Won't Work to a Problem That Simply Doesn't Exist'

Maverick FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai on why net neutrality and government attempts to regulate the Internet are all wrong.

Things were tense at the end of February, as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) prepared to vote on a proposal that would revamp the way Washington regulates the Internet. The 332-page document put forth by Chairman Tom Wheeler aimed to shift the classification of broadband Internet service from a Title I information service to a more heavily regulated Title II telecommunications service. Wheeler had made general information about the outlines of an earlier version of the proposal public, but, as is common at the FCC, the full text had not been released.

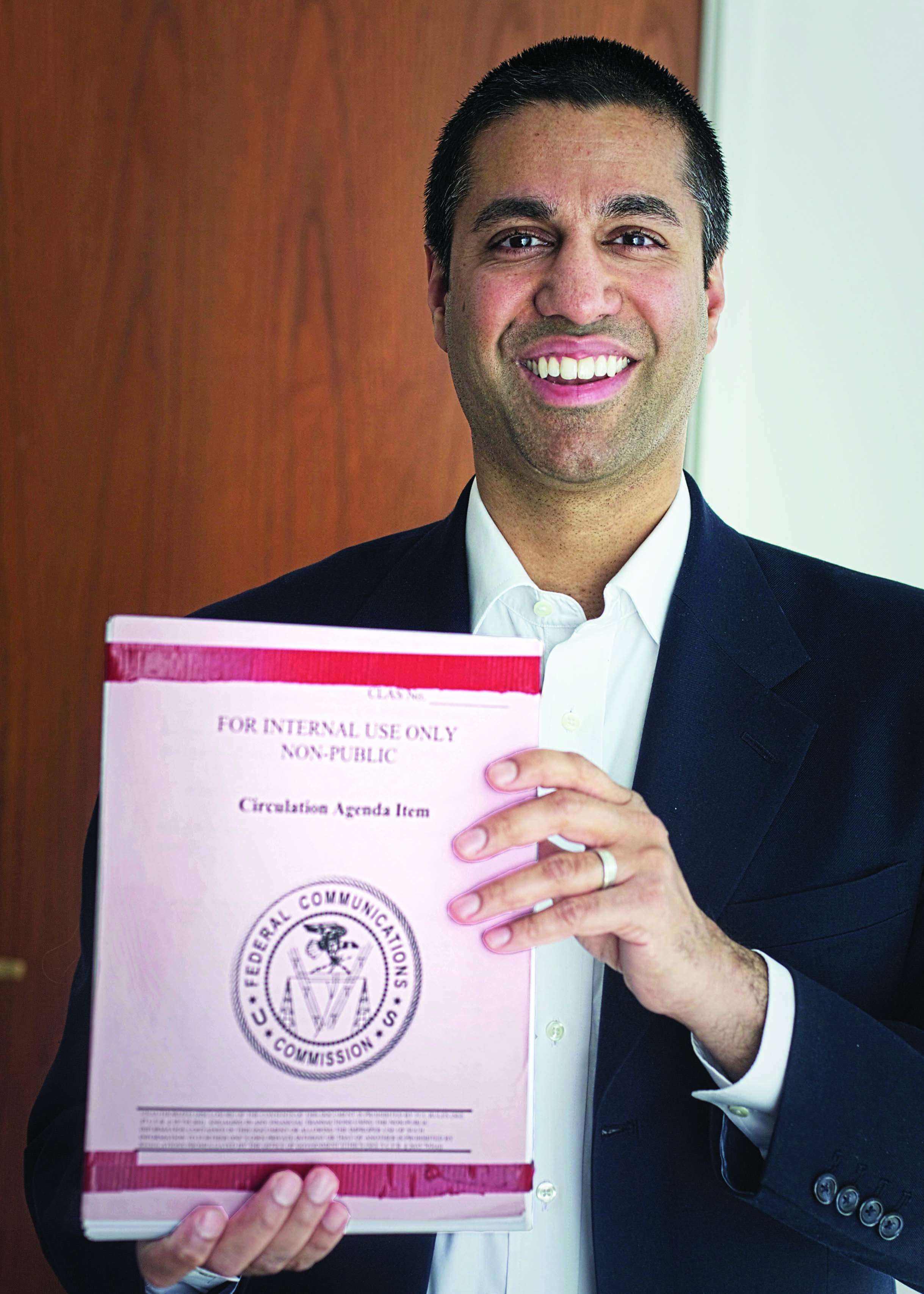

As the deadline neared, outspoken FCC commissioner Ajit Pai took to the airwaves he regulates (and the social media sites he doesn't), requesting that the commission's vote be delayed and the document released to the public: "The future of the entire Internet [is] at stake," Pai declared in conjunction with his fellow Republican commissioner Mike O'Rielly. But it was to no avail: The FCC ruled 3–2 to regulate the Internet.

Pai, educated at Harvard and the University of Chicago, has long been an opponent of net neutrality regulation and other measures to increase the power of the government over the Internet. The 42-year-old son of Indian immigrants spoke with Reason TV's Nick Gillespie just days before the controversial vote. For video of the interview, go to reason.com.

reason: Everyone says they want a free and open Internet. What are the points of agreement and then where does it get fuzzy?

Ajit Pai: I think [former FCC Chairman Michael] Powell put it best when he said in 2004 that there were four basic Internet freedoms that he thought everyone should agree with: the freedom to access lawful content of one's choice, the freedom to access applications that don't harm the network, the freedom to attach devices to the network, and the freedom to get information about your service plan.

Everybody, or virtually everybody, agrees on that. I certainly do. The question is how do we operationalize that? In my view, the federal government is a pretty poor arbiter of what is reasonable and what is not, and it's exceptionally poor when it comes to having a track record of promoting innovation and investment in broadband networks. That's something the private sector has done a remarkable job of on its own.

reason: What are the instances that net neutrality proponents can point to where Internet Service Providers (ISPs) or other network operators have actually violated those open network principles?

Pai: There are scattered examples that people often cite: an ISP that nobody's ever heard of called Madison River almost a decade ago. MetroPCS, an upstart competitor of course, basically had no market power to speak of compared to the other carriers. [The company] wanted to make a splash in the market place, so it offered its consumers virtually unlimited data plans for $40. You could stream YouTube for example without it counting against your data cap, all for $40.

reason: But basically you could only stream YouTube videos, right? The rest of the Web, you really couldn't get on it?

Pai: Exactly. So critics called it a net neutrality violation, called it a "walled garden," which was bad for consumers. It's telling that they didn't go after one of the major incumbents, which now they complain about vociferously. They went after an upstart competitor.

reason: MetroPCS was saying, "We're going to give you less for less, but if you want it, you can have it."

Pai: [For net neutrality proponents,] you either get to eat all you can eat at a restaurant, or you don't get to eat at all.

reason: So that's the idea of net neutrality?

Pai: Essentially.

reason: So what do you think are the main drivers behind net neutrality? From my perspective, when I look at things from a kind of public choice economics idea, what I tend to see are companies like Netflix, Amazon, to a cer

tain degree Google, eBay, other players who are very big and have done very well with the way that the Internet works now, and they want to freeze everything in place. This, to me, seems a lot like the robber barons when railroads were starting to be regulated who were like, "Great, let's regulate things and fix our market positions." Is that wrong to think of that in those terms?

Pai: I certainly think there are particular companies that might see a strategic advantage in having the FCC inject itself for the first time into the nuts and bolts of the Internet's operation. For example, regulating the rates and terms on which ISPs and edge providers [such as YouTube, Amazon, and iTunes] have to interconnect. That's something that, if you're not getting what you think is a good deal through private commercial agreements, might be helpful to have an FCC backstop.

There are a lot of other people, smaller entrepreneurs and innovators that we hear from, that are worried that ISPs might end up acting as gatekeepers and keeping their content off the Web. While I understand their concern, I nonetheless think that (1) there's no existing example of that, and (2) the way to solve that is through case-by-case adjudication using the antitrust laws or Federal Trade Commission authority, or even FCC authority to the extent we have it. It is not imposing Title II regulations, which ultimately and ironically are going to limit the progress of this online platform.

All these startups and innovators are based here for a reason. It's because we have the best Internet infrastructure in the world. But that network doesn't have to exist. People don't have to invest in it, and ultimately, this could be counterproductive for them too.

reason: You've called out Netflix in particular, which has probably been the most vocal proponent of net neutrality and of Title II regulation. They apparently have a system where they gain an advantage by the way they code some of their streams. Essentially, you and others have suggested that they've created a fast lane on today's Internet. Why would that be wrong?

Pai: To be clear, I don't think that Netflix should be subject to regulation, but when it came to this question, we heard an allegation in the fall from people who are pushing open video standards-everyone from ISPs to [content distribution networks] Level 3, Limelight, and the like. They wanted to create a system in which essentially traffic would be recognized as being video traffic, and then you could optimize the network to deliver it more efficiently, [with a] better experience for the end user. Netflix, we heard, was encrypting some of that traffic to make it difficult, if not impossible, for that traffic to be recognized as video traffic. So I simply asked them: What's the gist of your response to these allegations, in particular allegations that they had done encryptions selectively, and they had picked in particular, encryption against the ISPs that were using open video standards before encryption?

If the interest is truly in a free and open Internet, then one could make the argument that what the company's arguing for when it comes to ISP behavior should apply equally to edge provider behavior.

reason: How did they respond?

Pai: Well, they responded that they employed an encryption to preserve the privacy of their customers; they didn't deploy it selectively. In any case, there weren't any ongoing FCC proceedings.

reason: Netflix was also involved in a kind of large battle that wasn't quite about net neutrality. But Netflix was saying that on Comcast in particular and a couple of other large ISPs customers were suffering through extended buffering times where the quality of the stream and its reliability weren't so good. The ISPs said, "Look, Netflix is generating a huge amount of traffic, and we need to build out our networks in order to handle this traffic and prioritize it." And Comcast in particular, they have a new deal with Netflix where Netflix basically pays them more so that they get a faster pipe into the ISP. Is that the way the system should work? Is there any reason to believe that ISPs were purposefully slowing down the stream of Netflix to their customers so that they could go back to Netflix and say, "You better pay the toll, or people are going to get a real choppy image?"

Pai: From a procedural standpoint, neither of those parties ever filed a formal complaint with us, so we don't have what you might consider objective evidence from the parties as to what exactly the nitty gritty of the situation was. All I can say is based on what I've read in the press. That said, I think the nature of the dispute illustrates the folly of involving the government in refereeing some of those disputes in real time. We simply don't have the ability to determine who was right and who was wrong.

Even if we had the legal authority to do it, which I don't necessarily think we do, but ultimately, if you look at the end result, these arrangements, which have been commercially reasonable according to both parties given that they signed it, have been good for consumers. Again, if there's some kind of systemic problem when it comes to peering and transit, and other kinds of interconnection, I'm certainly willing to have an open mind about it, but I think in the absence of that, we should let the commercial arrangements work themselves out.

reason: We're talking about this as if it's a battle between Comcast and Netflix or this company and that company, but ultimately, the measure of all kind of economic regulation, and certainly antitrust law, is how it affects the consumer. That Netflix has to pay more to deliver its service, or the ISP has to eat more costs, that's not the same thing as saying the customer is in a bad position.

Pai: Exactly. I'm an antitrust lawyer by training, and that's why I view everything through the prism of consumer welfare, and that's why I find it amusing when some of my coworkers say, "Oh, you're just shilling for ISPs or looking out for big business." At the end of the day, my sole concern is: What is going to produce a better digital experience in the digital age? And I truly believe that removing some of these regulations that are impeding on IP-based investment and getting rid of some of these antiquated regulations is the best way to promote competition, promote consumer welfare. Not over-the-top 80-year-old regulations that have been proven not to work.

reason: Recently, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler said that he's going to move forward with the FCC regulating the Internet under Title II regulations. That'll change the regulatory structure from that of an information service to a telecom. What is the most important thing that people need to know about that switch?

Pai: The most important thing that people need to know is that this is a solution that won't work to a problem that simply doesn't exist. Nowhere in the 332-page document that I've received will anyone find the FCC detailing any kind of systemic harm to consumers, and it seems to me that should be the predicate for certainly any kind of pre-emptive regulation—some kind of systemic problem that requires an industry-wide solution. That simply isn't here.

reason: So you're saying the Internet is not broken.

Pai: I don't think it is. By and large, people are able to access the lawful content of their choice. While competition isn't where we want it to be—we can always have more choices, better speeds, lower prices, etc.—nonetheless, if you look at the metrics compared to, say, Europe, which has a utility-style regulatory approach, I think we're doing pretty well.

reason: The FCC recently redefined what counts as broadband. But using the definitions in the agency's last roundup of the state of Internet connections, the FCC said that about 80 percent of households have at least two options for high-speed service. One of the things that people say is, "Well, we need to regulate the Internet because local ISPs like Time Warner or Comcast have an effective local monopoly on service." Is that accurate, and would that be enough of a reason to say, "Hey, we gotta do something"?

Pai: I certainly think there are a lot of markets where consumers want and could use more competition. That's why since I've become a commissioner, I've focused on getting rid of some of the regulatory underbrush that stands in the way of some upstart competitors providing that alternative: streamlining local permit rules, getting more wireless infrastructure out there to give a mobile alternative, making sure we have enough spectrum in the commercial marketplace. But these kind of Title II common-carrier regulations, ironically, will be completely counterproductive. It's going to sweep a lot of these smaller providers away who simply don't have the ability to comply with all these regulations, and moreover it's going to deter investment in broadband networks, so ironically enough, this hypothetical problem that people worry about is going to become worse because of the lack of competition.

reason: So do most people in America have a choice in broadband carriers, and do they have more choice than they did five years ago, and is there reason to believe they'll have more choice in another five years?

Pai: I think there are hiccups any given consumer might experience in any given market. Nonetheless, if you look on the aggregate, Americans are much better off than they were five years ago, 10 years ago. Speeds are increasing; the amount of choice is increasing. Something like 76 percent of Americans have access to three or more facilities-based providers. Over 80 percent of Americans have access to 25 mbps speeds. In terms of the mobile part of the equation, there's no question that America has made tremendous strides. Eighty-six percent of Americans have access to 4G LTE. We have 50 percent of the world's LTE subscribers and only 4 percent of the population.

reason: Many will say that part of the problem is that Europe, for instance, is so much more advanced than we are in terms of the speed of connectivity, the price of a connection, and the variety. Is that just wrong?

Pai: That is wrong. If you look at the Akamai State of the Internet report, for example, or other objective data, there's no question that America is better off, especially considering our relatively lower population density, in terms of deployment, speeds, prices, whatever metric you choose. Moreover, if you look at investment, in the U.S. it's $562 per household. In Europe, it's only $244.

reason: Why is that important?

Pai: It's important because we want to have a strong enough platform for innovation investment and online options as possible, but you won't get that if the private sector doesn't have the incentive to risk capital to build those networks. It's a pretty tough thing to build the nuts and bolts of the Internet, and if the regulatory system is one that second-guesses you every single step of the way, regulates your rates, tells you what service plans are allowed or not, regulates the commercial arrangements you have both within users and companies, you're going to have the European situation, essentially.

reason: You've talked about the proposal as being well over 300 pages. There have been accounts that that's mostly footnotes and addenda, and that the rules are about eight or 10 pages. Is that accurate?

Pai: The rules are eight pages. However, the details with respect to forbearance, the regulations from which we will not be taking action-that alone is 79 pages. Moreover, sprinkled throughout the document there are uncodified rules, ones that won't make it in the code of federal regulations, that people will have to comply with in the private sector. On top of that, there are things that aren't going to be codified, such as the Internet conduct standard, where the FCC will essentially say that it has carte blanche to decide which service plans are legitimate and which are not, and the FCC sort of hints at what factors it might consider in making that determination.

reason: What goes into something like that where you're saying, "We're the regulators and we're here now, and you've got to pay attention to us, but we're not going to tell you what you actually need to do"? That's passive-aggressive to the max, and is that a deliberate strategy, to say, "We want you to jump, but we're not going to tell you how high"?

Pai: I think part of the problem is that the rules don't give sufficient guidance to the private sector, regardless of whether they're public or not. Part of the reason I want them to be [made] public soon, in advance of the vote, is I think the American public and particularly the people who'd be affected by it deserve to see what regulations are going to be adopted before they're formally adopted.

reason: Why wouldn't the FCC just put the document out into the public when it was announced that it was going to be voted on? What is the history of the kind of secrecy of rule making or documentation in the FCC, and does this represent a break with that?

Pai: Under the rules, only the chairman has the authority to disclose this document, and he's said both to Congress and to the public that he's not going to do so, and he's cited the traditional practice of the FCC, which is to not reveal these proposals until after they're voted on. And he's absolutely right, that is the traditional practice.

reason: Is that a good practice?

Pai: In this case, it absolutely is not. If you look at how great the public interest is in this issue, the folks who have been advocating for net neutrality have told us repeatedly that the Internet is something unique among the FCC's responsibilities, that four million people have commented, the president himself has made specific comments about it, and so I think if ever we were to make an exception to the traditional practice, this is it. Moreover, it's not that big a leap to say that the FCC should be as open and transparent as the Internet itself. Simply publish the rules, let the American people see it, and I think they can make up their own minds.

reason: What role did the White House play in creating the Title II decision? A year ago, everyone was saying, "Well, Wheeler is not going to go with Title II. He's a former lobbyist or employee of the cable industries. He's not going to do that." So what role did the White House play in enforcing this decision?

Pai: I think the White House changed the landscape dramatically with the president's announcement shortly after the midterm elections that he wanted the FCC to adopt Title II regulations and said—and it's still on his website—"I ask the FCC to implement this plan."

reason: The FCC is technically an independent agency, right?

Pai: It is and always has been.

reason: So is it a break with past protocols for the president to be kind of demanding certain things?

Pai: It is a break, in my experience. I've served under a number of different chairmen during administrations of Republican and Democratic affiliation. I've never seen anything as high profile as this. There have been other examples of presidents weighing in with a letter or a phone call, that kind of thing. But creating a YouTube video and [posting to the White House website] very specific prescriptions as to what this agency should do, followed by the agency suddenly changing course from where it was to mimic the president's plan, I think suggests that the independence of the agency has been compromised to some extent.

reason: Mark Cuban recently said at a tech conference that in letting the FCC enforce net neutrality, "the government will fuck everything up." Do you agree with that?

Pai: Well, as an FCC regulator, I certainly can't say that I agree with his use of one of the seven dirty words. [Laughs.] But I will say that the gist of his sentiment is absolutely right. I mean, do you trust the federal government to make the Internet ecosystem more vibrant than it is today? Can you think of any regulated utility like the electric company or water company that is as innovative as the Internet? What Marc Andreessen, who developed the Netscape browser, and what other entrepreneurs are saying is that this is something that's worked really well and there's no reason for the FCC to mess it up by inserting itself into areas where it hasn't been before.

reason: You've also been critical of the idea that if the U.S. government gets involved in the regulation of our Internet, that sends a particular message to other countries that's not particularly good. Explain what you mean by that.

Pai: On the international stage, there was an effort at the International Telecommunications Union, which is an arm of the United Nations, and another for the current model of Internet governance, which has been multi-stakeholder or decentralized, to be changed. And a lot of foreign governments, especially oppressive governments, would love nothing more than to have more direct control over both the infrastructure of the Internet and the content that rides over those networks. The U.S., to its credit, has spoken with a single voice against such efforts, but I think to the extent that Title II and the FCC's plans to micromanage the same nuts and bolts of the network [come to fruition], it becomes harder for us on the international stage to make that case, to persuade other countries not to go down the same road. And I would note that this is the exact same position that the Obama administration itself took in 2009 and 2010 when one of our ambassadors at the State Department said specifically that he was concerned that Title II–style regulation would send a negative message to oppressive governments and would lead them to block or otherwise degrade certain kinds of Internet traffic.

reason: Where do your ideas come from? You're obviously very pro-free market. You mention you're an antitrust lawyer by trade. You're a Republican appointee by Obama, so what are the ideas that motivate your thinking process in terms of regulation?

Pai: Going back to college at Harvard and then law school at the University of Chicago, I was exposed to a view of the world through the lens of economics that recognized that when government is relatively restrained in terms of its intervention in the economy, there is unbounded possibility for the consumer or the citizen. And that's why I've been outspoken since I've been at the FCC in favor of policies that I think will get the government out of the equation to the extent necessary to allow innovation to flourish.

There's no question that capitalism, generally speaking, has been the greatest source of human benefit, much greater than any government program that's ever been designed. If you look at how many people have been lifted out of poverty by free market ideas, it's tremendous. And it's that kind of innovation that people often take for granted, because we live naturally in the moment, and so it's hard to see the sweep of history. But I can tell you that for people as old as me, I remember 20 years ago when the Internet was at its inception, it was hard to get news, it was hard to do certain things that we now take for granted on a smartphone. But now, thanks to people in the private sector taking the risk, investing the capital, and being able to count on a regulatory system that didn't micromanage them, that's delivered unparalleled value.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "'A Solution That Won’t Work to a Problem That Simply Doesn't Exist'."

Show Comments (304)