Lifetime Registration for Juvenile Sex Offenders Overturned in Pennsylvania

Yesterday the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that a lifetime registration requirement for juvenile sex offenders violates the state constitution because it creates an "irrebutable presumption" that they "pose a high risk of committing additional sexual offenses." In reality, notes Justice Max Baer in a majority opinion joined by all but one of his colleagues, the recidivism rate for people who commit sex offenses as teenagers is quite low: somewhere between 2 percent and 7 percent, which is comparable to the rates for other types of juvenile offenders. Yet Pennsylvania's Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act automatically puts minors 14 or older who commit specified sex offenses (rape, involuntary deviate sexual intercourse, aggravated sexual assault, and attempts or conspiracies involving those crimes) in Tier III, meaning they have to register as sex offenders for life. Although they can petition for removal from the registry after 25 years, the criteria are hard to satisfy, and in the meantime they face onerous requirements that isolate them and impede rehabilitation.

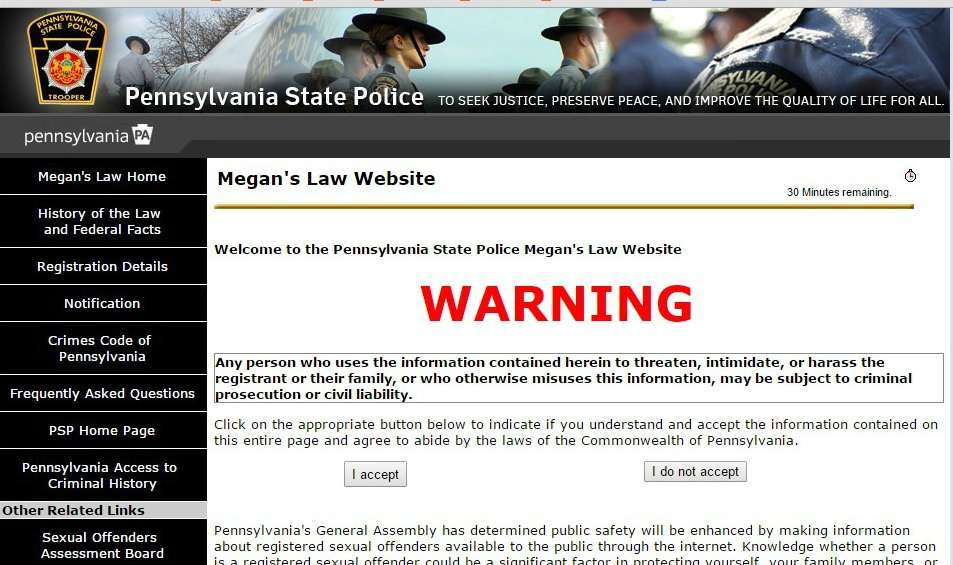

Among other things, Tier III offenders must register in person and be photographed four times a year, notify the authorities at least 21 days before international travel, and pay additional visits within three business days of changing residences, schools, jobs, telephone numbers, or email addresses. Failure to meet any of these requirements is a felony punishable by up to 10 years in prison for a first offense and up to 20 years for a subsequent offense. Inclusion in Pennsylvania's registry, which triggers inclusion in a publicly accessible national registry, is a long-lasting barrier to education, employment, and social integration.

These burdens, Justice Baer notes, undermine a central goal of the juvenile justice system, which is supposed to let people recover from youthful mistakes. He brings that point home by quoting a 2012 opinion from the Ohio Supreme Court:

For a juvenile offender, the stigma of the label of sex offender attaches at the start of his adult life and cannot be shaken. With no other offense is the juvenile's wrongdoing announced to the world. Before a juvenile can even begin his adult life, before he has a chance to live on his own, the world will know of his offense. He will never have a chance to establish a good character in the community. He will be hampered in his education, in his relationships, and in his work life. His potential will be squelched before it has a chance to show itself.

In concluding that such treatment violates juvenile offenders' due process rights, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court had to rely on the state constitution, since registration is not considered a punishment (even though it surely is experienced as one) and federal courts do not recognize reputation as one of the things that cannot be taken away without due process. The court also emphasizes the difference between juvenile and adult offenders, although the same concerns about exaggerated recidivism rates and lifelong burdens apply to both. The court says registration requirements for juvenile offenders should be based on "individualized risk assessment" instead of broad generalizations. Surely that also makes sense for adult offenders, who too often are lumped together based on the sexual nature of their crimes without regard to the threat they pose.

Pennsylvania adopted the law overturned yesterday in response to a congressional mandate enforced by loss of federal grant money. But as Baer notes, there's an out: Under the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act, a state can keep its grant money if its highest court determines that the federal government's policy preferences violate the state constitution.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

The softies in the Commonwealth's Supreme Court are suckers for redemption tales.

Yep. Might as well just open up the gaols and loose the criminals on an unsuspecting public.

Way to go, PA!

Fuck Adam Walsh, I hope he chokes on all his good intentions.

"In reality, notes Justice Max Baer..."

Max Baer the boxer? Or his son, Jethro Bodine?

mmm...Miss Ellie May, out by the seement pond.

Hope granny's cooking up a fine mess of vittles.

Miss Jane Hathaway had a bitchin' Chrysler Imperial

/only thing I remember from that show...besides Ellie May

Jethro had a lot of careers, but I don't think judge was one of them. Her was a "hill judge" though, so maybe the title got passed down.

Her= Jed. Fucking autocorrect.

PA got something right? It must be like when the refs in an NFL game call 10 bullshit penalties in a row on a team and then try to call an offsetting bullshit call in their favor because they feel guilty for being so wrong.

Ya but they're still all knee-touchers at Penn State

So what about all the other lifetime removing of rights, like the 1994 Brady Act effectively removing some peoples 2nd amendment rights forever?

No fucking law passed by congress or any other lower governing body should be able to remove a guaranteed constitutional right from anyone, ever. You want to do that, amend the fucking constitution.

Sam Good man is not going to like that..

http://www.Way-Anon.tk

No he is not!

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children updated their sex offender map on December 15, 2014.....there are now 819,218 men, women & children registered. http://www.missingkids.com/?/documents/Sex_Offenders_Map.pdf

The decision in this article is very encouraging and hopefully the beginning of reasonable reform as the new number of registrants above does not represent the original intent of a registry. The goal was to register and monitor the violent repeat offenders..that's it. Now we are spending millions and millions of taxpayer dollars to register, track and monitor registrants, most of which will never re-offend. Some states use risk assessment as a tool to determine the likelihood and this should be done in ALL STATES even though it is not an Adam Walsh Act (SORNA) mandate. From the day of sentencing the system should be designed to treat, rehabilitate and reintegrate. But, instead many are not treated while there and leave with the mandate to participate under threat of incarceration for another felony if non-compliant. There are so many laws and restrictions that essentially sets them up to fail when there is NO empirical evidence to support that action being taken.

It is a known fact that tiering levels are designed to place a large majority of registrants in the Tier III or High Risk category to justify the need. There are a huge number of offenses that are now registerable.

It is time to dial back on the laws and restrictions and allow our registrant families to live as a family instead of continuing the punitive punishment. There are 819,218 registrants and that means over 3 million wives, children, moms, aunts, girlfriends, grandmothers and other family members experience the unintended consequences of being harassed, threatened, children beaten, have signs placed in their yards, homes set on fire, vehicles damaged, asked to leave their churches and other organizations, children passed over for educational opportunities, have flyers distributed around their neighborhood, wives lose their jobs when someone learns they are married to a registrant....all these things occur when these people try to hold their family together and provide the three things that academics and researchers state are needed for successful re-integration; a job, a place to live and a good support system. over 3 million of our family members.

I recognize that our U.S. Supreme Court Justices have not acknowledged that the public registries and residence restrictions are punitive but they will have to rule that it is soon. It's just a matter of time.

Vicki Henry, President

?Women Against Registry dot com

[url=http://www.guccisunglasses.us.com][b]gucci sunglasses[/b][/url]

cartier sunglasses

chanyuan2017.01.6

pandora jewellery

air max uk